Uncomfortable truths: Taking an Introduction to Holocaust & Genocide Studies class

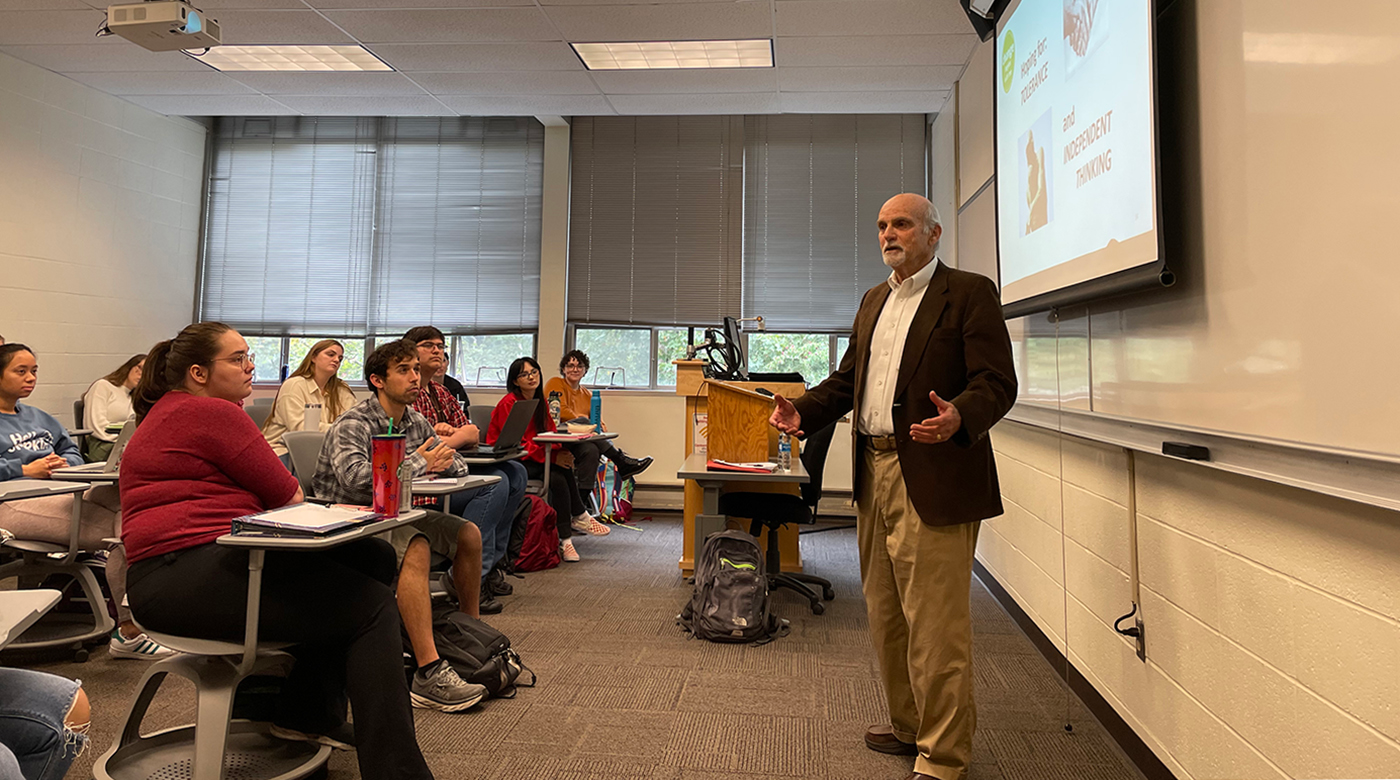

Image: Holocaust survivor Peter Metzelaar speaks with PLU students in a course titled “Introduction to Holocaust & Genocide Studies.” (Photo courtesy of Professor Lisa Marcus)

By Anneli Haralson

Marketing & Communications Guest Writer

“There is nothing comfortable about studying genocide,” Beth Griech-Polelle, a Pacific Lutheran University history professor and the Kurt Mayer Chair in Holocaust Studies, says. “It’s filthy, violent, degrading, and the worst of humanity.” Yet Griech-Polelle says the study and discussion of these atrocities are crucial to stopping them in the future.

PLU was the first university in the Pacific Northwest to offer a minor in Holocaust and genocide studies, beginning in 2014. For many PLU students, exploration and reflection on this subject begins with the “Introduction to Holocaust & Genocide Studies” course, which serves the minor but is also a general education course open to all PLU students.

Professors from the history, English, German, religion, social work and Hispanic Studies departments worked together to create the course to allow students to investigate the intersections of dehumanization, violent oppression, cultural destruction, and war. “We wanted to highlight the interdisciplinary and global focus of Holocaust and Genocide Studies beyond studying the history alone,” remembers PLU English professor and Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies Lisa Marcus, who was one of the co-creators of the course.

The class is team-taught by two professors, offering two different perspectives on the subject. Regular instructors include Rabbi Bruce Kadden and professors Rona Kaufman and Giovanna Urdangarain.

This past fall, Griech-Polelle and Marcus taught the course and led students through the Holocaust, Armenian, Cambodian, Rwandan and Native American genocides. Each genocide is its own unit with its own texts, explored both individually and comparatively, through a combination of historical texts, films, memoirs, and first-person testimonies. This fall, Marcus and Griech-Polelle had funding to invite survivors and/or descendants of survivors from each genocide studied in the course, thus giving students a more personal and immediate way to think about each genocide and its legacy in the present.

“While it’s important for students to have a basic understanding of chronology, they don’t need to obsess about dates,” Griech-Polelle says, explaining that some students avoid history because they think it’s all about memorizing dates. “I want them to know real stories and what drove people to make the decisions they did. I want them to understand how people were convinced to not only hate these other people, but were able to rationalize killing them. That’s the only way to ensure it won’t keep happening.”

The approach seems to be working. Both professors have noticed their students are especially interested in the guest speakers. During the Holocaust unit, students heard from two speakers: Peter Metzelaar, a survivor who fled Amsterdam with his mother and was a Hidden Child; and Chris Browning, a leading Holocaust historian, author, and former PLU professor.

“He was supposed to stay for an hour, and we went way beyond, but they all stayed and wanted to hear what he had to say,” Griech-Polelle recalls. “We thought that was a nice testament to how engaging he was. They lost track of time.” Students noted in the course reflections how powerful it was to hear directly from one the world’s most significant Holocaust experts and the author of their reading on perpetrators.

Similarly, Marcus says students were “captivated” by Silong Chhun, a second-generation survivor of the Cambodian genocide. He was born in the forest as his mother fled the Khmer Rouge and is now the digital communications manager at PLU. “It’s really crucial to have the perspective of the second-generation who experienced the aftermath of genocide, including migration and trauma,” Marcus says.

For Marcus, a key to teaching about genocide lies in language, specifically propaganda. She studies how, in genocides and wartime, propaganda and hate speech contribute to dehumanization and violence and asks students to extrapolate how harmful, racist, and “othering” language used today could lead to the same dangerous end. “How do we get to that point where language is no longer “just” language? Once you start putting people in categories, it leads down this very dangerous path,” she says. “Our hope is that when students hear a stereotype (such as that Jews or Asians are somehow responsible for the Covid-19 pandemic), they’ll recognize the danger and reject that way of thinking,” Marcus says.

That’s what keeps Marcus and Griech-Polelle going amidst the sadness and ugliness of the topics they teach. “It’s about connecting it to behavior here and now,” Griech-Polelle says. “There are much broader lessons that students can take from this: ‘How do you conduct yourself? How do you treat people? Are you respectful?’ That is what inspires me, because otherwise it would just be too sad and depressing.”

Marcus agrees, adding that antisemitism and racism continue to plague communities across the world. “Genocide is an ongoing problem with over 30 countries currently at risk of mass atrocity,” she points out. “Also, and significantly, the US still hasn’t come to terms with the genocide of Native Americans and African-Americans. We want our students to leave our class thinking deeply about issues such as the ongoing legacy of cultural genocide and what might be owed in terms of reparations.”

Inspired by a Jewish concept called tikkun olam, which refers to actions one takes to repair and improve the world, the final unit of the course is centered around the question “What Can We Do?” which asks students to think about interventions and repair work that take place in the post-genocide context. Students conduct research and create a poster and presentation about an organization of their choice that works to repair the atrocities of genocide. Past projects have highlighted people working to destroy Cambodian land mines and those working with rape survivors and their offspring in Rwanda.

“It’s really just amazing and a powerful aspect of the class that left students, not in despair or thinking that the world is a terrible, evil place, but knowing that they could get involved,” Marcus says.

Social Media