Are you brave or are you insane for coming out at a Lutheran university in the 90s… or are you just doing the right thing?

Beth Kraig (full oral history interviews part one, part two, and part three)

Beth was the obvious choice for the first person to interview for this project. For many PLU students and alumni, Beth Kraig is the queer history of PLU. I knew that Beth would also be instrumental in connecting me with other members of our PLU community who would be willing to share their experiences. I also knew Beth’s razor-sharp memory would be essential to mapping out the scope of this project.

Beth arrived at PLU in 1989, after a two-year stint teaching at Elon University (Elon College at the time) in North Carolina: a state where same-sex intimacy was banned and where Beth was living with her long-term partner, Suzanne. They both wanted to wind up in Washington (Beth had grown up here and attended UW) because, “more than anything,” they loved the Northwest. It helped that Washington had eliminated its, in Beth’s words, “so-called ‘unnatural sex law,’” and that there was a job posting for a year-long sabbatical-filling position in the history department at PLU.

Regarding PLU’s religious and social climate, Beth said that at the time, she was “at least vaguely aware of the fact that the ELCA part of the Lutheran Church writ large was more progressive on most issues, such as ordaining female-identified pastors,” but that it was also “very clear to me when I first came to PLU that … there were no out faculty or staff.” This meant that the PLU Beth was arriving at was, at best, lukewarm on its views towards queer people; at worst, covertly anti-queer; and PLU’s Lutheran identity played a prominent role in discussions on campus about social justice.

How do you assess the risks of coming out at a Christian university with very few (if any) openly queer people?

Tom Campbell, Professor emeritus of English, and one the first two openly queer faculty members at PLU.

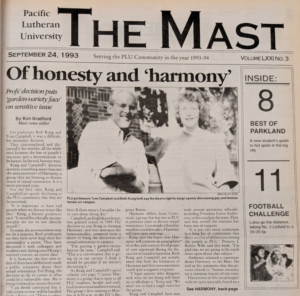

Though Beth had already made the decision with her partner that she did not want to be closeted during her time at PLU, she did not come out right away. She remembers being at a talk given by a PLU professor which, though intending to be about anti-sexism, subtly verged on being anti-queer. This moved Beth to discuss plans to publicly come out with colleague Tom Campbell. Tom had been, in Beth’s words, “itching to come out” after arriving at PLU in the mid-80s. Beth test-ran her coming out with a group of students in one of her 1993 summer classes, and “that’s when the ball was rolling.” Beth and Tom then visited the offices of different PLU administrators—not to ask permission, but to let them know “this is coming… so you have an opportunity from your standpoint to do whatever thinking you need to, because it will almost certainly get attention.” After speaking with each other and their partners, Beth and Tom came out in the September 24, 1993 issue of The Mast.

Both Suzanne and I had agreed that we would not have my career linger for any length of time as one where there’s a closet involved.

Notably, Beth was up for tenure as this news hit the presses. In the Mast article, she said, “I am firmly convinced that it will be handled fairly … There is safety here. If there wasn’t, I wouldn’t be so sure about doing this.” Beth did achieve tenure, and it didn’t appear as though the article impacted the process.

Coinciding with their announcement, Beth and Tom launched the campus organization Harmony, which Beth describes as “an effort to change the atmosphere around educating for the purpose of equity and inclusion at PLU, with queer-identified folks at the center of that, for that particular part of the process.”

The reactions to their announcement were mixed across campus, though not completely unexpected, at least according to Beth. She had felt and found it to be the case that “particularly young adults, students, would be far less likely to be committed to anti-queer prejudice,” though not all faculty followed suit. While some community members made their anti-queer sentiments known, overtly or implicitly, other staunch allies came out of the woodwork.

Beth reacts to the question “Are you brave or are you insane for coming out at a Lutheran university in the 90s… or are you just doing the right thing?”

Beth’s coming out left an indelible mark on campus at the time, and particularly on the queer and allied Lutes who looked up to her. Brian Norman credits Beth, and her leadership by example, with helping him learn “how to think not only at the sort of philosophical or political righteous level, but also how to roll up your sleeves and do the hard work of making institutions actually the best versions of themselves.” Colleen Hacker and Nikki Plaid both conveyed their awe over Beth’s decision to live as an openly queer faculty member.

For Colleen, Beth’s choice was “so brave.” For Nikki, her decision took on an even deeper significance as Nikki grew up and understood the professional stakes that she and Tom were facing: “That was their job. That was their livelihood. That was them. Going for tenure, that was not an easy decision that they made, and it was so incredible. … It could have gone very differently.”

Fannie Lou Hamer (left) and Ida B. Wells (right): two of Beth’s “historical mentors” and two figures featured in her courses on African-American History and Women’s History in the US. Read more about Hamer here and Wells here.

When I asked Beth how she feels about these retrospectives from her colleagues and former students, she told me that “it didn’t feel incredibly brave.” Even with uncertainty and fear, Beth said, “I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I knew what I thought I could try to make happen.” She brings up the stories of her own “historical mentors,” as she calls them, and the ways that they might reflect on their own bravery — or, more accurately, the obligations they felt towards doing what was just. Beth adds that “What you see when you look closely is that the person at the time very seldom feels like they’re being some sort of amazingly courageous person… They just feel like this is the right thing.”

After her coming out and the creation of Harmony, Beth’s commitment to advancing social justice did not wane, and her activism did not end there. Besides being the official and unofficial advisor and mentor to a number of student groups and individual students, Beth has consistently pursued antiracist, antisexist, and pro-queer advocacy for her students and colleagues (and everyone else) in the classroom, at campus forums, in committee discussions, and as of late, on Zoom.

In our last conversation, Beth shared some historical insight for those who want to make change and take individual actions towards justice: