How do you move institutions towards living the values they claim to hold?

Brian Norman ’99 (full oral history interview here)

Brian Norman was a “first-generation college kid from a small town in Oregon” with default “what I could now call libertarian or Republican tendencies, but nothing that was conscious or particularly thought through.” Coming to PLU in the 1990s, he had his worldview expanded at first by the holistic liberal arts curriculum, and then by his journey towards coming out himself.

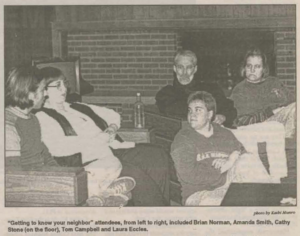

This image from an article in The Mast in 1997 features openly queer members of the PLU community answering questions from their peers and students.

Harmony and Crossroads had already been established by the time Brian reached PLU, and he attended both. He also took Lisa Marcus and Beth Kraig’s famous co-taught class that introduced him to the political dimension to sexuality, which was transformative for him and other members of Harmony.

“I think it gave a lot of people space and language to talk about their own — and not just their own identity, but the world in which they were finding themselves, and also gave them a little glimpse into the kind of activism that students could [use to] figure out mechanisms and models and histories to go about making change beyond a sort of like micro level of a student group,” he said.

Brian described his time at PLU as a heyday for novel queer and gay visibility, at least in many respects. He said there were definitely instances of homophobic hostility that he and his peers encountered, but none individually come to mind — he’s more likely to remember homophobia that occurred later in his life and career, when he began to have the sense that this was not something he would “just have to accept,” but something he could actively challenge and move towards a world with zero tolerance for it.

The social scene for queer students was flourishing, with “lots of parties, lots of communal living, and lots of debauchery of various sorts,” Brian said. “But I think, you know, I also think it was a community of care. I think it was a community that cared about each other and looked after one another. Which is important.”

Brian describes his approach to advocating for the inclusion of sexuality in the non-discrimination policy of the university.

Brian drew on this community support to engage with a network of fellow queer students (he met his long-term partner, Greg, at PLU), and plugged himself in to working to advance queer safety and visibility on campus in other ways. Most notably, he worked with Beth Kraig to research other ELCA schools that were already adding sexual orientation to their non-discrimination statements, as part of an effort to make the case to the PLU administration that this would not be in conflict with the institution’s Lutheran values. Brian’s time working with the microfiche in Mortvedt library directly translated into PLU’s eventual decision to update its non-discrimination policy in 1998.

The Mast breaks the news that the administration has added sexual orientation to the non-discrimination code for students in 1998.

That didn’t mean that campus, or even queer groups within it like Crossroads and Harmony, was free of tension, though. Brian described a heavy pressure on faculty members and students alike to be visibly out. Following in the footsteps of mentors like Beth and Tom, queer students prioritized this as the most surefire way to create social change on campus.

“There was that moment at PLU, like in American history, there was a sort of sense of duty or responsibility for those who could, to be out,” Brian said. “Of course, coming out is an ongoing process that never ends and takes all sorts of forms, but to create spaces of visibility which create cover for other folks who are, you know, at different moments in the process or experiencing life situations where they’re not able to be out.”

After graduating PLU with a major in women’s studies, Brian went on to go to graduate school in literary studies and became a scholar of African American literature. He has continued to work within institutions of education to challenge them to live by their own values, a commitment he solidified at PLU.

Notably, one of Brian’s capstone projects was a queer history of PLU — an early precursor to this project.

“So there was a moment, even that early, of an attempt to document, and an awareness that progress had been made, and that we were entering new chapters. I think that’s always an important moment of social change — when people start to perceive themselves as having history, which is to say having a series of victories,” he said.