Restoration in Chambers-Clover Creek Watershed

By Chelsea Escalante, Brennan LaBrie, Emma Mickelson, and Aaron Pantoja

Clover Creek, which trickles out of a natural spring near Frederickson and journeys through Parkland and Lakewood before emptying out in Lake Steilacoom, might be unrecognizable to those who knew it over a century ago.

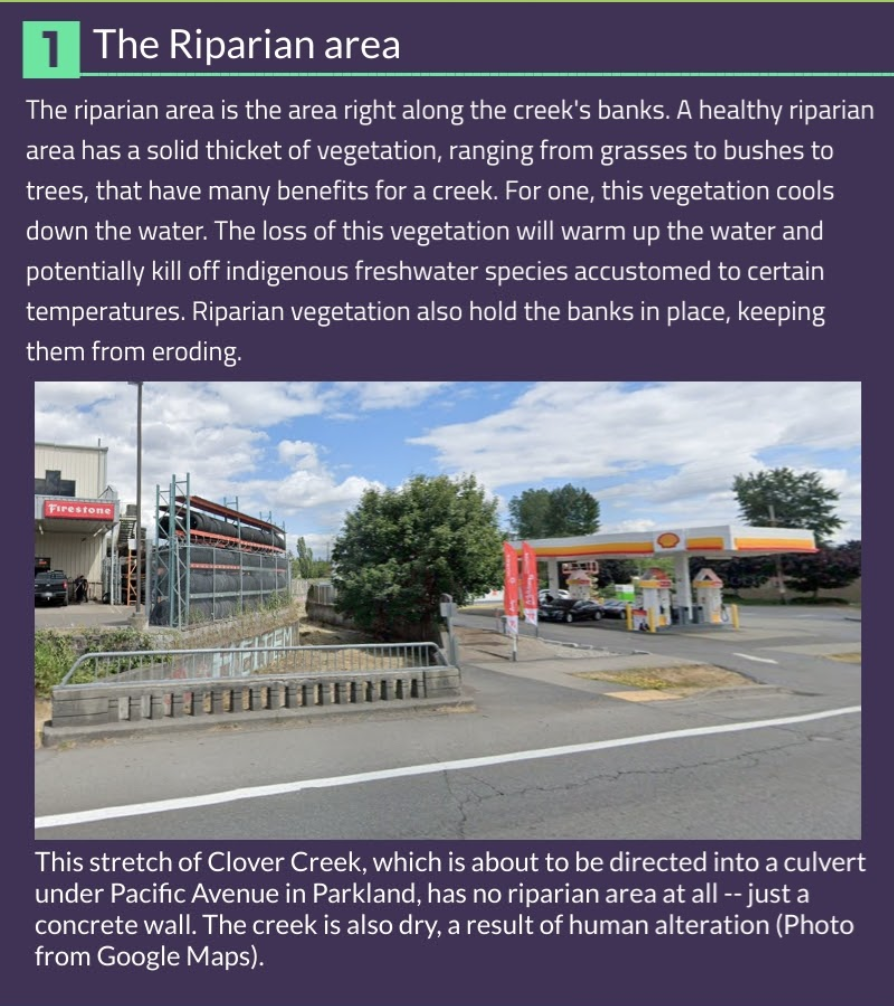

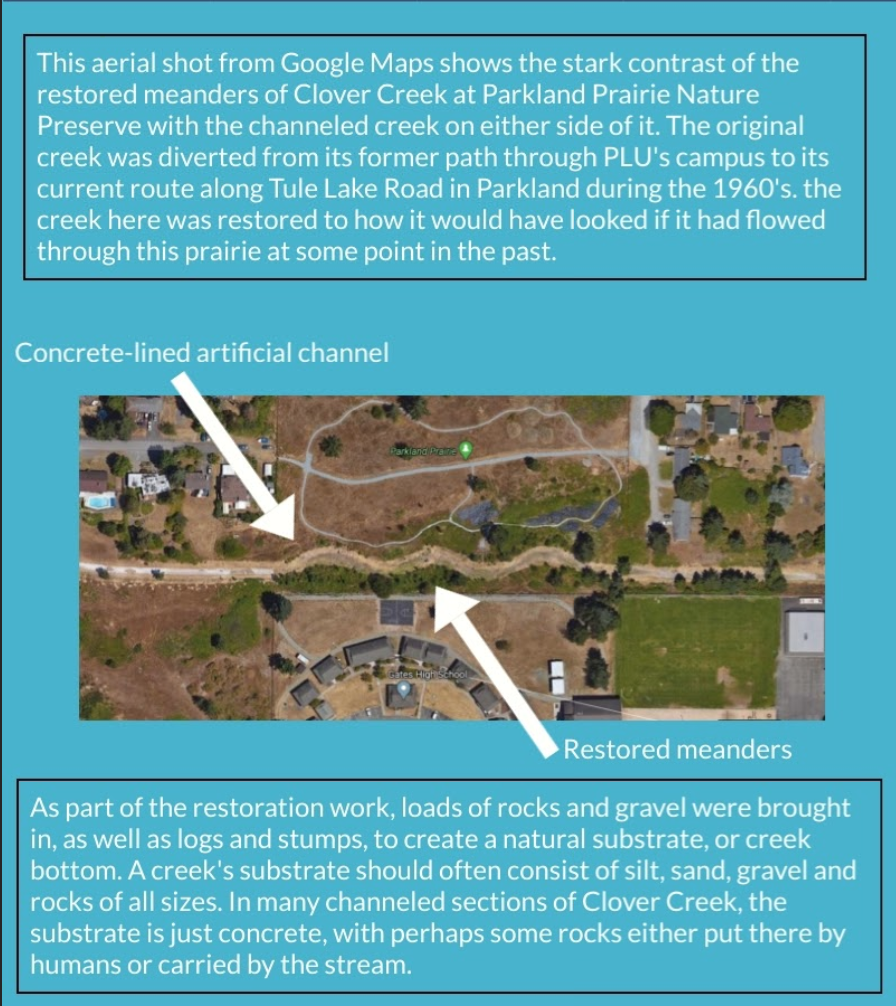

Residents along the creek in the early 20th century recall a thriving creek that would flow year-round and was ideal for fishing and swimming during the warm months. However, as the urban sprawl of Tacoma spread southwards and the unincorporated areas of Frederickson, Parkland and what is now the city of Lakewood developed, the creek was heavily altered to accommodate this growth. Much of it was straightened, its bottom (substrate) and sides lined with concrete. A long stretch of the creek was channeled under Joint Base Lewis McChord in an underground culvert. At certain points, the creek was diverted from its natural path and into artificial channels. Dams and weirs were built to make for easier fishing. The groundwater that helps feed the stream was pumped for construction, watering lawns, and other uses. Sometime in the 1940s, these factors, as well as other alterations, came together to result in the creek going dry for the first time in anyone’s memory at the time.

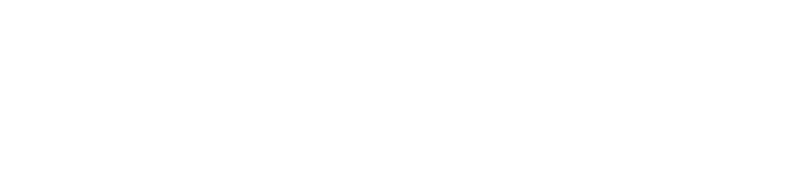

Since then, the once ever-flowing creek has become an intermittent creek, meaning it dries up during certain parts of the year. With the water went the salmon. People driving by Pacific Avenue in Parkland in the summer might not realize the dry concrete channel by the road is actually the creek that, along with Chambers Creek which flows out of Steilacoom lake to the Puget Sound, creates a watershed that encompasses most of the Tacoma metropolitan area and includes most of its major lakes.

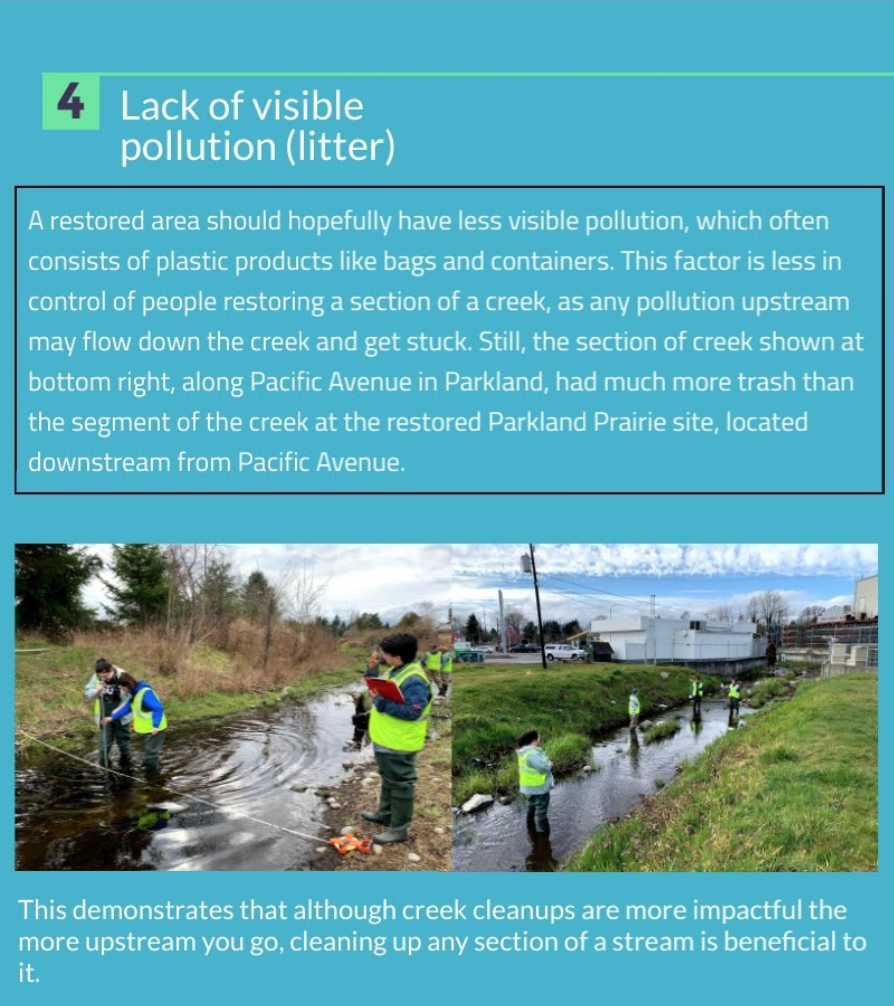

Even when the creek flows strongly in the spring, the effects of development are present in less noticeable ways. The lawns, houses and parking lots that push up against its banks where riparian vegetation once reigned have made seepage of fertilizers, sewage waste and gasoline, among other pollutants easy, which can kill fish and pets, and produce algal blooms that choke out native vegetation. Visible pollution, or litter can be found along the creek’s shores as well, a much more obvious manifestation of the negative effects of development.

We are students in the Environmental Studies 350 class at PLU, which for the last 28 years has been dedicated to studying Clover Creek and its health through analyzing its biological chemical, geological components, as well as its history — from its importance to regional indigenous peoples to the settlers in the 1800s who began altering it to the creek we see today. One area of interest for us in our studies are places where the creek and its surrounding was restored to its natural form or preserved from alteration. Two such places were the Clover Creek Reserve and Parkland Prairie Natural Reserve in Parkland.

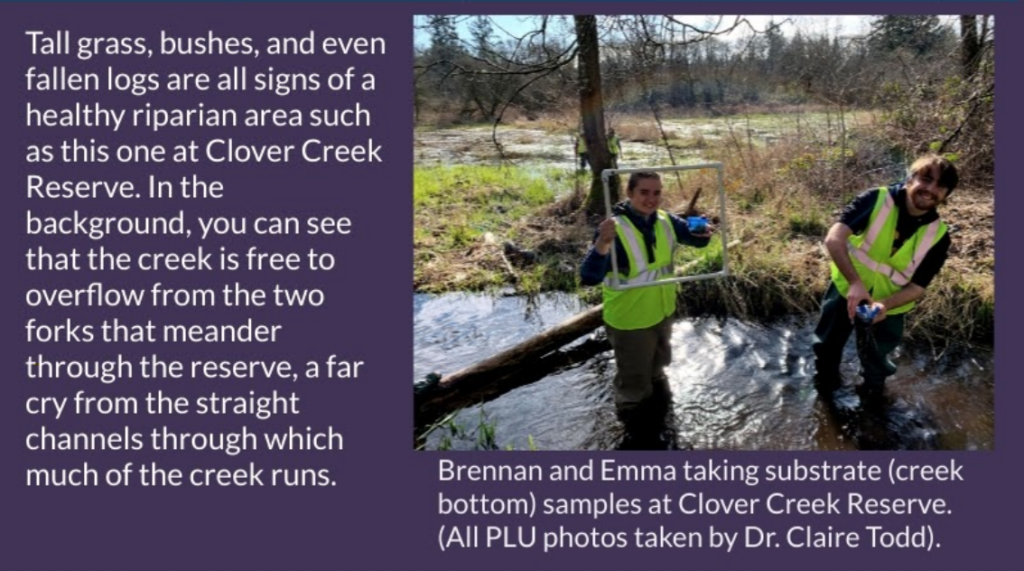

Clover Creek Reserve consists of 18 acres of protected prairie land, oak woodland and riparian habitat. Forterra began stewardship of the property 2000, and since then has been working hard to preserve the rare and native flora and fauna of the landscape. There are two channels that run through the Clover Creek Reserve. Riparian habitats are influenced by river/streams and include shallow backwaters. These habitats offer shelter and food to attract the species that live in this environment. The top priorities for restoring environmental factors are habitat diversity and water quality. The loss of habitat quantity has been severe in some areas due to flow changes.

What We Have Learned Studying Clover Creek:

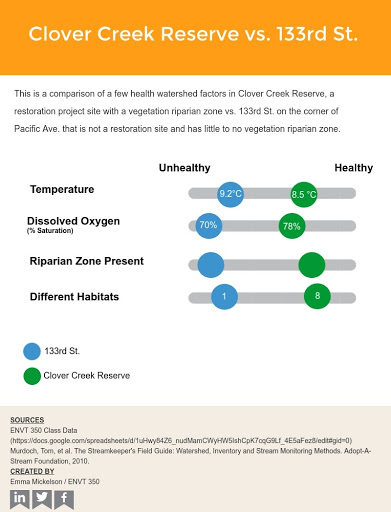

Below are pictures comparing the health of the watershed at a location that has been restored vs. not restored.

Using data from the ENVT 350 collected in February 2020 and the Department of Ecology State of Washington from 2008-2012, we compared the health of Clover Creek Reserve, the restorated site and 133rd, the non- restorative site.

This data shows that the restoration improvements are beneficial in keeping a healthy ecosystem and stream. Overall, Clover Creek Reserve is a lot healthier than the 133rd St. location. A lot of this is due to the restoration efforts put into Clover Creek Reserve. Restoration is important for all areas of the watershed but especially at upstream locations. A watershed transports, holds, and collects water that all exits out on one location (Streamkeeper’s Field Guide). This means that water quality in downstream locations is affected by upstream sites.

Putting effort in restoration in upstream locations will benefit all of the other downstream sites. Restoring an area focusing on the diversity of natural environments is key in sustaining wildlife habitats, wildlife, plants and animals for the region. Healthy vegetation and riparian zones have helped improve water temperature, dissolved oxygen levels, and created a space for diverse vegetation to grow.

Specific Data:

In February, at Clover Creek Reserve the water temperature was recorded as 8.2 degrees C and WADOE has an average temperature of 10.8 degrees C. This temperature is in the range that would support native salmon species in the stream (Streamkeeper’s Field Guide). Restoration allows for vegetation and healthy riparian zones to provide shade for the stream, lowering water temperature.

Another factor is dissolved oxygen. At Clover Creek Reserve we measured the dissolved oxygen to be 10.8 in February and the WADOE data from 2008-2012 has an average DO being 9.6. Compared to the water temperature, this gives Clover Creek Reserve a dissolved oxygen % saturation 78% and 88% respectfully. A healthy area has a saturation percentage of 90%-100% (Streamkeepeer’s Field Guide). This is a little low but is likely from the organic material present from the vegetated riparian zone. This material is a food source for other aquatic species and without restoration efforts would not be there (Streamkeeper’s Field Guide).

Overall, restoration efforts at Clover Creek Reserve have benefited water quality in the area which is important for other downstream sites and the watershed as a whole!

Supporting local restoration projects can help lessen the impacts of urbanization on the watershed. Since water is critical for both people and animals alike, having the watershed’s best interests at heart is essential for the health of both the environment, and the people and animals living in it not just now, but for years to come.