When Two PLU Historians Sit Down to Chat

Image: History professors Beth Kraig and Rayne Allinson enjoy yet another lively conversation

By Dr. Rayne Allinson

One smoky August afternoon Dr Beth Kraig and I decided to beat the heat and take shelter in the cooling confines of the University of Washington, Tacoma library, to have a cheery chat about plagues.

We thought this would be a fun topic to discuss, given that most of last year’s graduating History majors chose

John Kelly’s The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (2006) as their parting gift from us.

Had the state of the world degraded so badly that our students had developed morbid obsessions? Or did they see a connection, as Beth (who specializes in 20th Century US History) did, between global anxieties about AIDS, Ebola, and flu pandemics, and the devastating bubonic plague, which wiped out 25 million people in Asia and Europe when it first emerged in 1347?

Or did students’ book choice connect more to binge-worthy TV shows like The Walking Dead, where a mysterious mutating pathogen leads to a zombie apocalypse? We were determined to put our historical heads together to find out.

Well… that was until we actually sat down together, and found ourselves merrily distracted (as Historians are wont to be) by questions of how and why we got here in the first place.

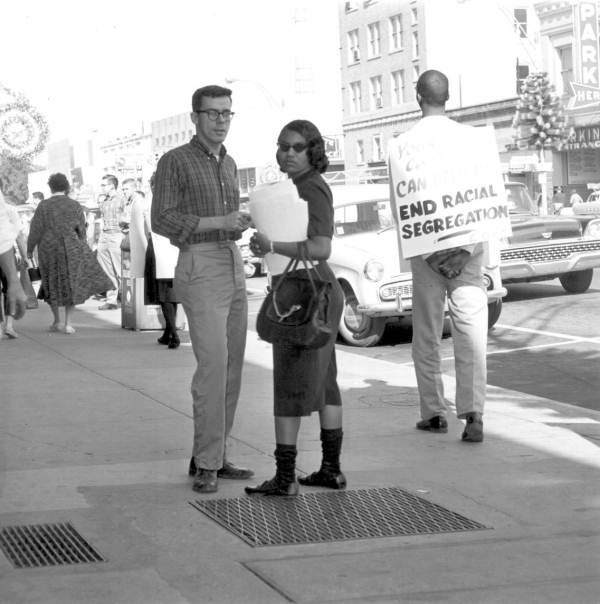

Beth shared how her love of History started early, listening at the dinner table to her parents’ wide-ranging conversations on civil rights protests and other 1960s events. (It turns out this was a memory we both shared – only instead of the Pacific North West, my dinner-table eavesdropping took place on a dairy farm in south-eastern Australia!).

Beth found herself attracted to the human stories of the past – especially, she says, to questions of authority — although answers were often lacking in the monotonous, dry-as-dust lectures she encountered at university.

After graduating with a BA from San Francisco State University in 1979, she did some traveling in the US… but also, amazingly to me, all the way to Australia, where she developed an interest in Aboriginal history and its resonance to Native American experiences.

This was exciting for me to hear, since I had just returned from a trip home to research a new study-away course on Aboriginal History – a trip which proved so interesting and absorbing, it prompted me to wonder why I hadn’t studied Australian history more at university. Looking back, I told Beth I thought there were a few reasons.

Growing up in a place that felt so far away from the rest of the world made me hungry to escape it and — like Beth, I had been fascinated by where modern political authority came from – which led me to study Renaissance Europe. But I had also been an undergraduate at Melbourne University during a particularly challenging moment for Australian historians. In 2002, a historian named Keith Windshuttle published a book called The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, which claimed that historians had grossly exaggerated the extent of frontier violence against Aborigines in colonial Australia

So I went to the University of Oxford for doctoral research on Elizabethan diplomacy, while Beth traveled to Bellingham to complete her MA in History, then to Chicago for an MA in Library Science, and finally back to Washington to research women’s history and questions of social activism for her Ph.D. Interestingly, neither of us, it seems, had set out on our paths intending to become university professors. We had simply been lucky in various ways to be granted the opportunities to follow our passion for ideas, stories, and the mysterious forces of human nature.

After more than an hour’s engrossing conversation, we realized we had wandered a long way from our original point of departure – history books, plagues, and zombie apocalypses! Though in a way, we found we had actually been answering our own question in a roundabout (typically historical) way, by following the thought-trail of why we are drawn to the topics we find ourselves researching and teaching about. I guess I’ll just have to ask my Early Modern Europe students why they think the Bubonic Plague of the 14th century still has relevance for them today.