لوگ کیا کہیںگے / Log Kya Kahenge

By Elsa Kienberger

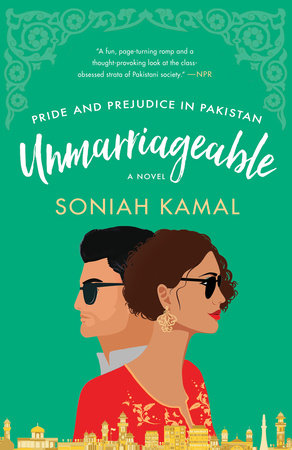

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), describes a society whose members, constantly fearing the loss of personal reputation, ask themselves this question like a reprimand: What will people say? The title’s timeless alliteration also displays how words shape reputation’s near relation–memory. Soniah Kamal’s Unmarriageable (2019), a retelling of Austen’s novel, explores the way in which language impacts cultural and personal memory. Set in Pakistan in the early 2000s, the novel follows Alys Binat and her sisters as they navigate the marriage market, female identity, and British and Pakistani influences on their self-expression. Kamal translates “What will people say?” into Urdu: ” کہیںگے/ Log kya kahenge” (35). She applies a post-colonialist perspective to the question by asking not only how society will judge an individual’s actions, but how Pakistan will speak for itself as it works through the aftermath of British rule and the imprint of the English language on the multiple languages spoken in the country. Simultaneously, the novel challenges Britain to redress its colonial history. Kamal is under no allegiance to false unification. She represents the pluralistic perspectives of Pakistan through a diverse cast of characters. Her novel aims to unsettle the British literary canon in order to make a place for itself, more characters of color, and non-English languages not only in popular memory, but also in current vernacular.

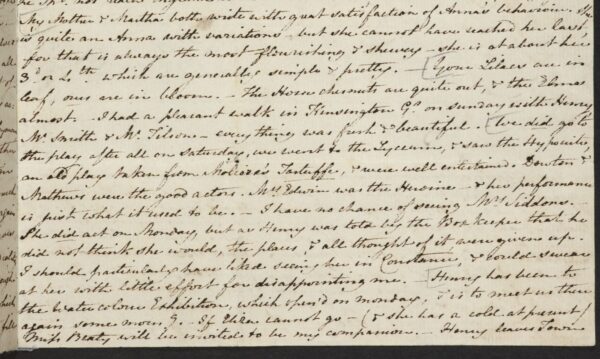

Kamal’s personal experience with literature growing up in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the USA motivates her re-examination of a British literary “canon” populated by white authors. She originally completed what would later become Unmarriageable for her MFA thesis at the University of Georgia in 2017. Her personal essay ” Pride and Prejudice and Me” (2019), found in the book’s endmatter, details her creative inspiration: “I wanted to write a novel that paid homage to Jane Austen and Pride and Prejudice, as well as combined my braided identification with English-language and Pakistani culture, so that the ‘literature of others’ became the literature of everyone” (352). Alys also expresses this sentiment in a conversation with one of her former students about the latter’s ideas for a doctoral thesis on Austen. She tells her to “[d]iscuss empire writing back, weaving its own stories” (Unmarriageable 83). Kamal’s diction places an emphasis on “braiding” and “weaving”, crafts which preserve individual threads instead of assimilating them into one homogenous work. Similarly, Kamal holds multiple cultures between her fingers while maintaining their distinctions. The novel’s epigraph signals the tapestry Kamal weaves and unweaves through her writing. First, an 1813 letter from Austen to her sister, Cassandra about her feeling that Pride & Prejudice would benefit from “something unconnected to the story” to ground it; second, Thomas Babington Macaulay’s 1835 “Minute on Education” in which he claims that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia” (no pg n.). “لوگ کیا کہیںگے / Log kya kahenge?”, Kamal seems to ask in her novel, if people cannot write in their native languages. What does it mean when Kamal and Alys express themselves in English?

One scene in particular portrays the deep psychological effect that colonialism’s power over language has on contemporary Pakistani culture and Alys herself. While in Pak Tea House, Wickaam asks Alys how it feels to be surrounded by wall to wall photographs of “Local Literati Legends?”:

“A little sad that they might have as much, if not more, to say to me than Baldwin or

Austen, Gibran or Anzaldúa, but since I can’t read Urdu fluently, though I do try, that’s

that. Anyway, hurrah for translations.”

“Too much is lost in translation”, Wickaam said (130).

Their conversation displays how the prioritization of English over other languages in Pakistan, like Urdu, affects Alys and Wickaam’s sense of identity and belonging to their culture. Alys’s list of literary figures she relates to includes women and people of color who have traditionally been left out of the literary “canon”. Still, she longs for an author who shares her own nationality and can better mirror her own lived experiences—an author like Kamal.

Both Alys and Kamal might see themselves in Arundhati Roy’s 2018 W. G. Sebald Lecture on Literary Translation presentation “What is the Morally Appropriate Language in Which to Think and Write?”. She argues that “[w]riting or speaking in English is not a tribute to the British Empire […] it is a practical solution to the circumstances created by it” (np). Alys cannot read Urdu due to factors tracing back to Britain’s colonial rule over the peoples who would eventually live in Pakistan, and Kamal’s use of language in her novel reworks the idea of English as a “practical solution” (Roy np). Wickaam points out the limitations of translation, yet as the parallel of Austen’s Wickham, he knows better than many of the characters how persuasive a personal translation of events can be.

Kamal’s novel is a personal translation. Writing in English, she showcases Pakistan’s multilingualism by incorporating Arabic, French, Hindi, Punjabi, and Urdu into its pages: from “log kya kahenge” (Urdu) to Alys’s last name “Binaat” (taken from the Arabic “banat” meaning “girls”) to foods like “bhindi” (Hindi) (35, 353, 119). Some English translation always follows unless the word or phrase is repeated or if it is a title of a work. In each case, every language is written in its romanized form, likely a Ballantine Press print standardization, but one that nonetheless caters to the English language’s Latin alphabet. By writing in English, Kamal speaks to women like Alys who might not read Urdu but need to see themselves represented in literature. If Kamal writes about the boundaries language and society set for individuals, especially women, and particularly women in Pakistan, Kamal’s linguistic pluralism precedes Alys’s social barrier crossings. As Kamal traverses language with comfort and discomfort, Alys delicately forms a path for herself between class and national allegiances.

Pride and prejudice around social classes form the basis for Alys and Darsee’s initial dislike of each other as it does between Elizabeth and Darcy, yet Alys’s conflict with language is part of what ultimately makes Darsee so appealing to her. He has studied outside of Pakistan, read international literature extensively, and feels caught between worlds just as she does. His gift to her of Attia Hosain’s Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961) represents their commonalities because the novel (set during the Partition of India) speaks to their shared feelings of pride and confusion as Pakistani citizens. It also literally represents their common language of English. Darsee shares how “That book made me believe I could have a Pakistani identity inclusive of an English-speaking tongue” (117). Unmarriageable is Kamal’s contribution to a Pakistani literary “canon” that can “have more to say” to both Alys and Darsee (130). Whereas Austen’s Pride and Prejudice presents a biting ridicule of the contest for social mobility and a sharp eye to gender restrictions in Regency England, Kamal turns her eye to England’s imperial legacy in the life and language of contemporary Pakistan.

At times, the novel’s meta-references detracted from my suspension of disbelief because I was always aware that I was reading a retelling of Pride and Prejudice. All of characters know about the novel, Alys teaches it to her class, and at the authorial level, Kamal wrote Unmarriageable as an adaptation of the original for her thesis. Although the characters are incredibly well-versed in Austen, they frustratingly never fully realize how their lives parallel Austen’s novel. For instance, Alys and her friend Sherry (Charlotte Lucas’s parallel) explicitly compare their lives to Pride and Prejudice in one scene and note only dissimilarities besides the social power structures that limit their choices (149). The mysteriously-maladied Annie even speaks directly to Austen and Kamal when she says: “I decided that, no matter how ill I got, I’d never turn or be turned into Anne de Bourgh” (225). Caroline Bingley’s parallel, Hammy, symbolically reveals her feelings for Darsee when she exclaims “I love Mr. Darcy” and then goes on to embarrass herself by mistaking the 1995 BBC mini series for the novel (118). Kamal conveniently sets her novel before the 2005 Joe Wright movie adaptation starring Kiera Knightley, so Hammy saves herself additional fan-girling over Matthew MacFadyen. And yet, precisely because Unmarriageable constantly reminds us of the framework of Austen’s novel, it asks us to confront Western influence and ponder how the specter of British colonialism hangs over the lives of its characters.

This comes to a point in the epilogue, when Alys and Darsee visit the Jane Austen House Museum in Chawton Village. Kamal places them on the colonizer’s land and sets the stage for a kind of reclamation of space and language. As a result, her novel and the many languages it contains, its unapologetic critique and celebration of Pakistan, and postcolonial arguments enter into the physical space of British culture, from which Pakistani literature has long been denied. Standing inside Austen’s home, Alys and Darsee reject Macaulay’s claim of the “intrinsic superiority of Western literature” and the exclusivity of the British literary canon by opening up a place on the shelf for Unmarriageable.

لوگ کیا کہیںگے / Log kya kahenge? / What will people say?

انہیں جو کہنا ہے وہ کہنےدو / Unhein jo kehna hai woh kehne do. / Let them say what they want.

Unmarriageable: A Novel, by Soniah Kamal

Ballantine Books (2020)

Hardcover, Paperback. eBook (384 pages)

ISBN: 978-0525486480, $11.95

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Sameen Zehra for proofreading and editing the Urdu translations in this review.

Images Cited

“200 Years of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ Book Design”. The Atlantic. 25 January 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2013/01/pride-and-prejudice-200th-anniversary-covers/318349/.

Books. Unmarriageable. Soniah Kamal. Penguin Random House. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/567399/unmarriageable-by-soniah-kamal/. Accessed 2 January 2020.

Kamal, Soniah. “About Me”. http://www.soniahkamal.com/about-me/. Accessed 2 January 2021.

Works Cited

Kamal, Soniah. “Unmarriageable”. Unmarriageable. pp. 1-332. New York: Ballantine Books, 2019.

—. “Pride and Prejudice and Me”. Unmarriageable. pp. 349-352. New York: Ballantine Books, 2019.

—. “A Note on the Names in Unmarriageable“. Unmarriageable. pp. 353-356. New York: Ballantine Books, 2019.

Roy, Arundhati. “What is the Morally Appropriate Language in Which to Think and Write?” Literary Hub. New York: Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature, 25 July 2018. Web.

Social Media