Carrie Cracknell’s Anne Elliot is a Girl with a Rabbit

By Adela Ramos

As Katherine Voyles’ insightful essay on the discourse around Persuasion (2022) demonstrates, historical inaccuracy has been pegged as one of Carrie Cracknell’s unforgivable misdeeds, especially related to the use of contemporary language and even the protagonist’s bangs. Yet when I finally watched the film, I was pleasantly surprised to find that Cracknell draws on the visual and literary culture of Austen’s era in the choice to associate Anne Elliot (Dakota Johnson) with animals. When Anne first introduces her family, she is carrying a pet rabbit who will be by her bed, on her lap, and in her arms, when she breaks the fourth wall. In her first conversation with Lady Russell (Nikki Amuka-Bird), the camera frames Anne next to a stylized bird (possibly a white heron) from the wallpaper background. In the poignant swim scene at Lyme, one of many beautiful cinematographic moments, the camera tilts vertically away from Anne to seagulls flying overhead. These scenes parallel how in Austen’s era women’s association with animals provided a means to laud feminine ideals, although this pairing was also used to satirize women, as Austen herself did—Lady Bertram and Pug will not let us forget. Yet, in trying to understand the significance of these parallels, I was left with the same question that at least fifty-one other people (on Reddit) have tried to answer: Why does Anne Elliot have a pet rabbit?

The Reddit forum highlights why the motif is confusing for readers of the novel since, as noted on another online venue, “[r]abbits aren’t mentioned in [Persuasion]” (Ajello). In fact, the novel does not depict any pets, except for the “long-petted Master Harry [Musgrove]” (Vol. II, Ch. 1, 146) [1]. In an adaptation, details such as a pet rabbit represent aspects of the novel that cannot be fully translated to the screen. Some have turned for answers to the Fleabag (2016-2019) guinea pig, a motif for the eponymous protagonist’s grief, remorse, and eventually, her recovery. So, if the rabbit is one more of the many pop culture references of Cracknell’s mashup, what is the connection to the protagonist?

These were the questions I sought to answer because my own disappointment with the film resided in the missed opportunity to draw out Dakota Johnson’s underexplored talent in her portrayal of Anne Elliot. In her recent performance in Maggie Gyllenhaal’s adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter (2021), Johnson stunningly portrays Nina, a sensual twenty-something grappling with deep ambivalences about motherhood while under the vigilant eye of a macho husband, her mother-in-law, and Leda (Olivia Colman), who is quietly obsessed with her. Johnson persuasively conveys Nina’s failed struggles to figure herself out while thus confined; this performance held promise for a portrayal of Anne, another woman in her late twenties who must find her way out of the social conventions she has ambivalently accepted. Instead, Johnson’s Anne carries a pet rabbit, who at times appears to be either a symbol of caregiving or a muted albeit obvious allusion to her sexuality. More than anything, though, the rabbit appeared to render Anne Elliot, Austen’s oldest protagonist and arguably the most heartbroken of all, a girl.

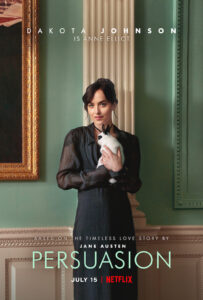

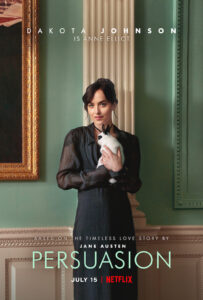

In the novel, we learn early on that the years since Anne and Wentworth’s estrangement “had destroyed her youth and bloom” and that she had to “[learn] romance as she grew older” (Vol. I, Ch. 7, 95; Ch. 4, 69). Cracknell’s film eludes destruction and aging by denying the protagonist emotional range and by thematically associating Anne with the transition between girlhood and womanhood. If we follow the scent of the film’s references to Austen-era iconography, it becomes evident that the rabbit is a perfectly suitable—and historically accurate—allusion to both the autumnal tone of the first part of the novel and to the possibility of Anne’s “second spring” (Vol. II, Ch. 1, 147). Rabbits were frequently portrayed with young women in allegories of autumn as harbingers of spring. The connection to Anne’s pet rabbit is evinced in the character poster for Anne Elliot, which is in conversation with eighteenth-century allegorical portraits, such as Rosalba Carriera’s (1673-1757) “The Girl with a Rabbit” (undated). Carriera’s portrait allegorizes autumn by creating a connection between the decline of girlhood and the rebirth and fecundity that await on the other side of winter.

Rebirth is congruous with the restoration of youth in Austen’s Persuasion, where later in life than other heroines, Anne comes into her own after a dark autumn and winter. At least in some instances, it turns out, historical inaccuracy is not where Cracknell’s Persuasion stumbles. Rather, and more importantly, it is in the confusion the film creates between the rebirth of a girl into a woman and the rebirth of a woman in her late twenties into self-possession.

Carriera’s portrait is representative of the popular eighteenth-century association between young women and small, soft, animals who symbolize the sitter’s own softness. Examples across European paintings of the period include Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s Girl with Dead Canary (1775) and James Northcote’s The Age of Innocence: Portrait of Miss Staley (1796). This softness alludes to innocence, female beauty, youth, and a temperament that requires—usually male—protection [2]. In Carriera’s allegory, these and other implications are established as we meet the sitter’s gaze, which invites us to turn to the rabbit. When we do, the maternal hand that holds the rabbit’s paw and chin leads us to her bare breast, which is highlighted by the painting’s chiaroscuro, a sign of her untainted sexuality, of fertility’s promise and, it follows, motherhood.

The meaning of the woman-rabbit relationship is familiar: then as now, rabbits are associated with sexuality, fertility, and spring. The famous natural historian, Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), qualified rabbits’ “fecundity” as “astonishing,” noting that a pair might produce as many as 1, 274, 840 offspring in the span of four years. Bewick also notes that rabbits begin reproducing at five months, which might further explain why this quadruped is companion to a young girl of budding sexuality—or, shall we say, in her “first bloom”? (342; Austen, Vol. I, Ch. 1, 50). The eroticism of Carriera’s portrait does not undermine the sitter’s innocence, which she emphasizes through her flawless white skin. A composite of innocence, sexuality, and fertility, the girl with a rabbit emblematizes the decline of girlhood and impending womanhood.

Anne Elliot’s character poster parallels Carriera’s in the position of Johnson’s face which is slightly turned and in how her gaze meets ours. She embraces her pet rabbit with the maternal protectiveness of her eighteenth-century counterpart. The rabbit’s eye is positioned in such a way that hers and Johnson’s eyes form a triangular composition that aligns them with the white neoclassical column at the center. Carriera’s aquamarine color scheme is also transferred to the poster as is a chiaroscuro gesture in how Johnson casts a shadow, setting her face and the rabbit’s white fur in bright contrast. The most notable difference is Johnson’s slate gray pelisse and dress, the same she wears in the opening scene of the film (without a pelisse) and when she realizes the mysterious man who caught her eye is her cousin, Sir Elliot (Henry Golding).

The color is appropriate for a protagonist who is not thriving, as Cracknell’s Anne states in the movie’s opening lines. Indeed, Austen’s Anne Elliot does not thrive until the trip to Lyme where she begins to appear “remarkably well; her very regular, very pretty features, having the bloom and freshness of youth restored” (Vol. I, Ch. XII, 132). However, despite its nod to this restoration via the rabbit’s symbolic connection to rebirth, Cracknell’s adaptation forecloses the return of Anne’s beauty and vigor. Her Anne is stuck in the first bloom, in a kind of nonage. With no room to move, it is inevitable that Johnson’s performance falls flat.

The unfulfilled promise of Cracknell’s nod to rebirth is on display in Anne Elliot’s swim in Lyme. This scene garnered snark and confusion, partly because it is framed by one of the most infamous lines: “Now we’re worse than exes—we’re friends.” What is troubling, really, is the conversation that precedes this statement. Wentworth confesses that, when lost in the alarm of battle, he channels Anne’s capabilities to respond in crisis—she would make a great Admiral. Like his later remarks about Anne’s caregiving qualities, these compliments carry the sound of flattery because at no point is Anne given the opportunity to show this supposed intrepidity, not even when Louisa falls. The flatness of Anne’s response to Wentworth’s hyperbolic compliments is uncomfortable but consistent with her characterization: she smiles coyly, lowers her head, and mutters gratitude like a bashful girl.

The swim that follows is out of tune with previous and subsequent scenes but quite meaningfully in line with the theme of rebirth. As Wentworth leaves, the protagonist drops her shawl, wades into the rising tide, even though he warns her to beware of the riptides. The camera sets us at eye-level with Anne, making us privy to this moment of autonomy. Wentworth looks back worried but resists the urge to protect her (which he has self-consciously admitted to beforehand). As we’re left floating in the cold water with Anne, no fourth wall needs to be broken. The camera tilts overhead to the flying seagulls, and we understand that this scene announces Anne’s rebirth, her impending freedom from familial and social constraints. In a movie that makes room for the restoration of youth, the swim would mark the contrast between Anne prior to Lyme and Anne in Bath. We do later witness her growing desire for Sir Elliot. But the complexity of her feelings for him and Wentworth that are so prevalent in the novel are drowned out by banter or, rather, ensnared by an octopus.

When the film’s romance and humor were over, I was left thinking about Johnson’s age—she is thirty-three—and Carrie Cracknell’s age—she is forty-two—and wondered why two women who surely have a lot to say about female experience chose static youth over growth. When sharing her interpretation of Austen’s heroine, Cracknell describes her as “out of place and somehow out of time” (Indiewire). This compelling view is not realized in the film. Cracknell makes Anne Elliot very much of this—our—time in the choice to freeze Anne in her first bloom. This choice must be paired with the movie’s erasure of Mrs. Smith, Anne’s thirty-year-old friend. In the adaptation of a novel that unequivocally condemns disparaging attitudes toward aging, Cracknell sides with Sir Walter (who refers to Mrs. Smith as an “old lady”) and his preference for static youth and beauty (Vol. II, Ch. 177).

In her study of age in Austen’s era, Devoney Looser reminds us that “youth and age are not measured by numbers alone” (80). As in Austen’s fiction, age is determined by gender, by social expectations (such as marriage) and life expectancy, dictated in a specific context and time. More recently, Looser invites us to think less of age, a static term, and more of aging, a dynamic and visible process that we all experience (28). If aging, understood as growth, had not been entirely removed from the story, I might be persuaded by a defense of Cracknell’s Anne that proposes she runs counter to prescribed notions about how women of a certain age must behave. But this is not the case. To be clear, I am not espousing the offensive remarks which targeted millennials and accused Cracknell of dumbing down the novel. Updating Austen is a surefire way to better understand her work and our time. And what Persuasion (2022) confirms for me about our time is that we are not interested in aging. Ours is a time of surgically preserved first blooms, as evinced in the faces of Hollywood actors (mostly women) and the dearth of stories about women in “the years of danger” and beyond (Vol. 1, Ch. 1, 49). I share the enthusiasm for adaptations that speak to my students, who are both traditional college age students and returning adults, and to viewers new to Austen. There are many such adaptations. I will be more enthusiastic about adaptations that offer female and female-identifying students a portrayal of mature women that is funny, sensual, and complex, that gives them something to look forward to, something more than a girl with a rabbit.

Many thanks to Christian Gerzso, Danielle Spratt, Elsa Kienberger, Madeline Scully, Misty Krueger, and Katherine Wiley for going down this rabbit hole with me and helping me think aloud and in writing.

- Don’t be fooled by Charles Musgrove’s dogs. They would be strictly distinguished from pets, the indoor companions who became popular in Austen’s time, and who are given affectionate names and are not at work in the field or employed for the hunt.

- Other related meanings that might be implicit in Carriera’s allegory include the rabbit’s early modern association with Venus and love, as well as to women’s cunning and sexual organs. See Victoria Dickerson’s wonderful study of the rabbit’s cultural and natural history Rabbit (Reaktion, 2014). In addition, rabbits, and their hare relatives, were favorites of the hunt and were also strongly associated with vulnerability in poetry of the time. Austen was very familiar with this poetry, as Madeline Scully notes in her annotation of Northanger Abbey. Austen was especially familiar with William Cowper’s poetry, who Fanny Price quotes in Mansfield Park (1814), and whose anti-hunting sympathy for the hare is immortalized in “Epitaph upon a Hare” (1784) and “The Task” (1785). Austen scholar Barbara K. Seeber has demonstrated that Persuasion is in dialogue with anti-hunting debates of Austen’s time in Jane Austen and Animals. Both rabbits and hares have been consistently feminized across history. I’ve written about the hare’s feminization in “The Hunting of the Hare: Female Virtue and Companionate Marriage in Henry Fielding’s Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones,” Reading Literary Animals: Medieval to Modern. Eds. Karen Edwards, Derek Ryan, Jane Spencer. Routledge,

Works Cited:

Ajello, Erin. “12 Details you missed in ‘Persuasion,’ Netflix’s newest rom-com starring Dakota Johsnon, July 15, 2022. https://www.insider.com/persuasion-movie-details-you-missed-netflix-2022-7

Austen, Jane. Persuasion. Ed. Linda Bree, Broadview Press, 2013.

Bewick, Thomas. “The Rabbit.” A General History of Quadrupeds, printed by and for S. Hodgson, R. Beilby, & T. Bewick, London, 1791, 341-343. https://archive.org/details/generalhistoryof01bewi/page/340/mode/2up?q=rabbit

Carriera, Rosalba. “Girl with a Rabbit” (n.d). The Huntington Art Museum Collections Catalog,

https://emuseum.huntington.org/objects/22835/girl-with-a-rabbit;jsessionid=A43CC5AAE8657EF23242273574625504. Accessed 8 Aug. 2022.

Cracknell, Carrie, director. Persuasion. Screenplay by Alice Victoria Winslow (based on the novel “Persuasion” by Jane Austen), Netflix, 2022.

Greuze, Jean-Baptiste. “A Girl with a Dead Canary” (1765). National Galleries Scotland, https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/4985. Accessed Aug 15 2022.

Looser, Devoney. “What is Old in Jane Austen?”. Women Writers and Old Age in Great Britain, 1750-1850. Johns Hopkins UP, 2008, 75-96.

———————. “Age and Aging Studies, from Cradle to Grave.” Age, Culture, Humanities, no. 1, 2014, 25-29.

Northcote, James. “Miss Staley” (1795). Royal Academy of Arts, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/staley. Accessed Aug 15 2022.

Seeber, Barbara K. “Too cool about sporting.” Jane Austen and Animals. England: Ashgate, 2013, 55-72.

Thao, Phillipe. “These ‘Persuasion’ Character Posters Will Help You Get over Your Ex”. July 11, 2022, https://www.netflix.com/tudum/articles/persuasion-poster-photos-dakota-johnson-henry-golding. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

Social Media