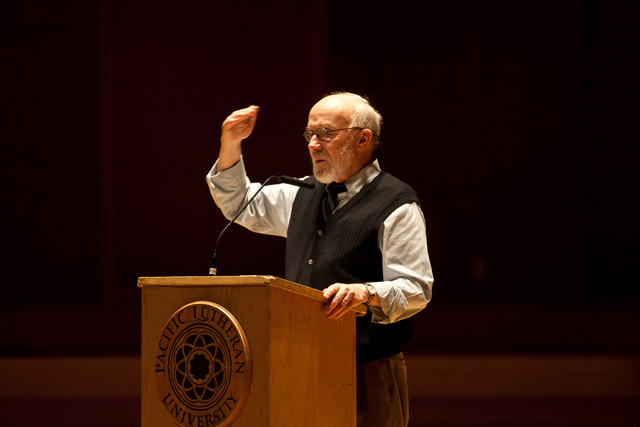

Marcus Borg, who serves as Canon Theologian at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland and Hundere Chair of Religion and Culture Emeritus in the Philosophy Department at Oregon State University, presented a lecture entitled, “Speaking Christian: Reclaiming Christian Language,” on Wednesday, November 3, at the 6th Annual David and Marilyn Knutson Lecture. (Photo by Igor Strupinskiy ’14)

Jesus scholar identifies need to reclaim Christian language

There’s an alternative and more biblical framework for understanding speaking Christian, said Jesus scholar Marcus Borg.“Religions are like languages,” Borg said. “To be part of a religion includes using, hearing and understanding that language’s religion.” The problem is, “for many people in our time Christian language is an increasingly unfamiliar language.”

Borg, who serves as Canon Theologian at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland and Hundere Chair of Religion and Culture Emeritus in the Philosophy Department at Oregon State University, presented a lecture entitled, “Speaking Christian: Reclaiming Christian Language,” on Wednesday, November 3, at the 6th Annual David and Marilyn Knutson Lecture.

The lectureship brings to campus nationally recognized scholars who creatively work within the historical, scriptural, and theological sources of a living faith tradition, bringing those sources into dialogue with contemporary questions and challenges.

Borg argued there are two central features of “common Christianity” that have shaped the meanings of much of Christian language and can explain why it’s becoming increasingly unfamiliar.

These features are the literalization of Christian language and an understanding, or misunderstanding, of Christianity’s core message.

Literalization of the Christian language—believing that all or even just some of the Bible is literally and absolutely true—is neither ancient nor traditional, Borg said.

“Biblical inerrancy and insistence on the literal interpretation of the Bible are modern products of the last few hundreds years,” Borg said.

Borg suggested an exercise: think back to the end of your childhood, age 10 or 12, and think about what you would have said about the heart of the gospel if you had to sum it up in a sentence or two.

He vividly recalled what his answer would have been at the time: “Jesus died for our sins so that we can be forgiven and go to heaven if we believe in him.”

“Even if you grew up in non church going family,” Borg said, “you would have formed such impression by age 12 or so.”

Analyzing his own response he said, “let me underline what it emphasizes, the afterlife. It emphasizes our sinfulness,” he said.

His response wasn’t peculiar to his upbringing, but it was and is central to common Christianity, Borg said.

Words have their meaning within contexts and frameworks, he said. Borg argued that the meanings of words in the bible are much different, richer and fuller than in our minds.

“The most common meanings of these words are simply wrong,” he said. They distort the biblical meaning, “hence the need to learn how to speak Christian again.”

As an example, Borg analyzed the biblical and contemporary meanings of the word salvation. Most people think the word salvation relates to sins and forgiveness, but nothing in the bible alludes to this, said Borg.

“It (salvation) names the aim, the goal, the purpose of Christian life,” said Borg, “and yet for many people it’s not only misunderstood, it’s a loaded word.”

Borg argued that the modern interpretation of the word salvation is “a terrible reduction of the meaning of that word.”

“Salvation in the Bible is primarily about transformation in this life, in this side of death, a two-fold transformation, a transformation of ourselves and the world,” said Borg. “Salvation is about reconnection. Salvation is about healing the wounds of existence and we all grew up wounded.”

Christian language is becoming increasingly unfamiliar because of a framework that has developed over the last few hundred year years, Borg said. Common Christianity, what most Christians learned and take for granted, has significantly shaped the meanings of much of Christian language.

Many who attended Borg’s lecture said they enjoyed the lecture and the approach Borg took to this topic.

“He speaks to all of the people who cannot embrace what they grew up with as children,” said Lynn Ostenson ‘71. “He gives people something to replace the traditional Christianity that isn’t working for them anymore.”

“I’m not a religion major so I don’t get a chance to study these things,” said senior psychology major Sarah Eisert of Borg’s lecture. “It’s a more cohesive critique of traditional Christianity and how it can be seen differently and in a way that I could understand.”