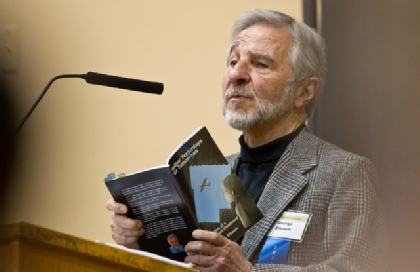

George Elbaum reads from his book “Neither Yesterdays Nor Tomorrows” about his survival in Poland during WWII. On the screen behind him is a picture of Elbaum and his mother taken shortly after the war ended. (Photo by John Froschauer)

Survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto talks about how his mother’s determination and “pure luck” played out in his survival

Suddenly, Elbaum’s mom, Pauline, appeared out of the crowd, waving a paper in front of the German guards. She worked in a ghetto factory making uniforms for the Nazis, and had managed to get her manager to sign a reprieve for her family – even though the entire block where the his family lived was being shipped off that day.

George Elbaum shares his story of survival, escaping the Warsaw Ghetto.(Photo by John Froschauer)

“She convinced the guard to let us go,” Elbaum said to a crowd that packed the Chris Knutsen Hall last week. “If she had arrived a few minutes later, we’d have been gone.”

Elbaum, 73, was one of the keynote speakers at the Fifth Annual Holocaust Conference at PLU last week. Elbaum, who later emigrated to the US with his mother in 1950s, then later attended MIT and became an aeronautical engineer. He didn’t speak of his experiences in Poland for over 60 years, until in 2009, he watched a documentary about a group of Kentucky middle schoolers who began studying the Holocaust by collecting paperclips to represent the 6 million Jews who perished in concentration camps during WWII. Elbaum admitted that he simply couldn’t face the pain of what he’d experienced, and didn’t think he’d have much impact anyway.

“But when I saw the school children crying in the film, after listening to a survivor, I realized that my story still has the power to influence people,” he said. In 2010, he completed his memoir of the time “Neither Yesterdays Nor Tomorrows.”

The cover page of the book shows a sketch of a young boy of about five, looking up through a hole in the shed at an airplane marked with Luftwaffe crosses. Elbaum said that ironically, seeing that plane, flying so high and free in the sky, sparked his later interest in aviation. That shed became a home for Elbaum and his mother, who smuggled their way out of the ghetto just weeks before the ghetto uprising, when the rest of its inhabitants were killed by Nazi troops.

The family hiding in the shack had to keep quiet around the clock, although one of the families did smuggle out the family pet, a dachshund, with them. Elbaum said he remembers the animal’s silky fur, and the fact he was able to spend some hours playing with in the animal to relieve the boredom. But one day, the dog was gone, and no one would tell him why. He learned later its owners had had to strangle the pet to keep it from barking when footsteps sounded outside the shed.

Eventually, his mother, who had dyed her hair blonde and took on the identity of a Catholic woman, moved Elbaum out of the shed and into a series of Polish families, moving him periodically when it became unsafe to stay with the families, or neighbors became suspicious. The final family he stayed with -and the only one where he remembered the father’s name – Leon- took Elbaum with them when they fled Warsaw just before the city’s uprising in 1944. On the way out of the city, the family stopped to rest and Elbaum, then about six, wandered out into a field, where he picked up what he thought was a toy with an odd pin at the top, which he pulled.

Just then Leon called Elbaum back to the road, and the boy tossed it into a ditch, where it exploded, harmlessly.

“As I said, luck,” Elbaum laughed.

When the war ended, Elbaum and his mother were reunited lived first in Warsaw, setting up book stores for the communist government, then Paris and then finally the US. The family came to New York, North Carolina and then Oregon.

“I remember really buying into the American dream that if you work hard enough, you can achieve your dreams,” said Elbaum, who graduated with four degrees from MIT.

He also urged listeners in the CK to make a choice, when they witness injustice, mob action or even bullying, to act.

“All of us can choose whether we are on the side of fairness and tolerance,” he said.