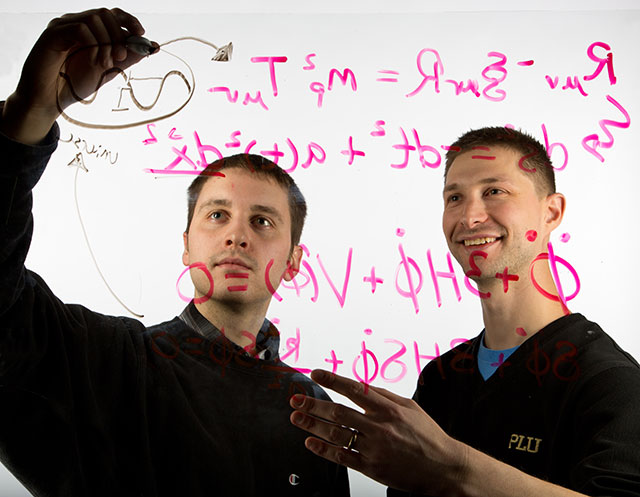

Auberry Fortuner ’13 and Assistant Professor Bret Underwood did research into understanding what gave rise to the expansion of the universe. (Photo by John Froschauer)

Modeling the Early Universe

None of us was around for the Big Bang, but one enterprising student is determined to see what the universe looked like in its beginning, more than 13 billion years ago.

Auberry Fortuner ’13 spent his summer simulating events that happened about one-billionth of a second after the Big Bang, trying to understand the conditions that gave rise to the cosmic inflation in which the universe grew exponentially.

“Understanding how the world really works is really enjoyable for me,” Fortuner said.

The Tacoma native knew next to nothing about cosmology when he began working on the project less than a year ago, but now he’s exploring territory uncharted by researchers.

Fortuner worked under the direction of Bret Underwood, Assistant Professor of Physics, on the student-faculty summer-research project, a continuation of Underwood’s work as an independent researcher before he joined PLU.

“I’ve been playing around with things on this theme for a couple of years,” Underwood said. “There are different ideas about how this period of inflation went about. … I was interested in how inflation started in these variations. The project we’re doing here is a further expansion upon that.”

These variations, small bumps and fluctuations in the smoothness of the universe, are variables in the equations Fortuner has been exploring. His findings show the amount of expansion and energy in the universe over time, and give insight into what parameters affect the physics of the very early universe.

Entering numerical codes into a computer program and running simulations for hours day after day wasn’t glamorous, but it’s been an invaluable experience for Fortuner – a physics major who almost failed his first physics class.

“When I took Intro to Physics class, the first college physics class, I did really bad. I was somewhat deficient in math. … I realized if I wanted to do this, I would have to catch up,” Fortuner said.

Although it was difficult, Fortuner was drawn to the subject. “It was something about just the skill,” he said. Working on problems, finding connections and understanding the world around him also motivated him to spend extra time outside of class learning the material.

“I wanted to continue learning it—mastering it,” Fortuner said. “I really enjoyed them (the lectures) and just being confronted with this really difficult subject, but in a classroom that was really supportive to help me understand.”

Fortuner’s hard work paid off when Underwood accepted him for his summer research project last summer.

Fortuner spent the first month researching cosmology and the very early universe.

Underwood, who participated in two undergraduate research opportunities when he was a student, let Fortuner really drive the research.

“It’s not very often that students get to do theoretical research,” Underwood said. “I’ve been very hands-off. I would say, ‘This is what we need to think about; go and see if you can get this to work,’ so Auberry would go off. It’s a great opportunity for them to get involved in research, exercise their curiosity, really become part of the scientific community.”

Fortuner carried out 15 to 20 different scenarios, or hypothetical universes, over the course of the summer. To the researchers’ surprise, each scenario ended with inflation, leading them to question their earlier assumptions.

“It didn’t seem to matter how you started the universe; it always ended up inflating,” Underwood said. “When you’re trying to describe the very early universe, you have to make many assumptions to go anywhere. Isolating which assumptions are important and which are not is part of the game.”

One assumption they left out was Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity: While they agreed the theory was true, Underwood said, their assumption was that it shouldn’t significantly influence the outcome when considered with their model.

Their summer ended with this realization, and after taking a break from the work during fall semester, Fortuner will pick up where they left off in the spring and use part of the research as his Capstone project.

“The capstone is going to pick up saying, ‘Let’s relax that assumption… and see what happens,’” Underwood said.

“It would make the equations a lot harder, but if we do tackle that, then I would have to go back and study more to be able to work with those equations,” Fortuner said. “The idea of having another challenging problem is exciting.”