Military Trailblazer Who Was Sexually Assaulted in College Will Share Her Story With PLU Audience

JBLM’s Lt. Col. Celia FlorCruz Speaks Feb. 17 as Part of PLU’s

“…and Justice for All?” Spring Spotlight Series

TACOMA, WA (Jan. 15, 2015)—Lt. Col. Celia FlorCruz has blazed such a major trail in the military that soldiers and civilians alike know the basics of her inspiring, groundbreaking career:

- She graduated from West Point as part of only the third class to admit female cadets;

- She flew helicopters as a Medevac pilot in Operation Desert Storm;

- She commanded a medical unit at Fort Drum in New York; and

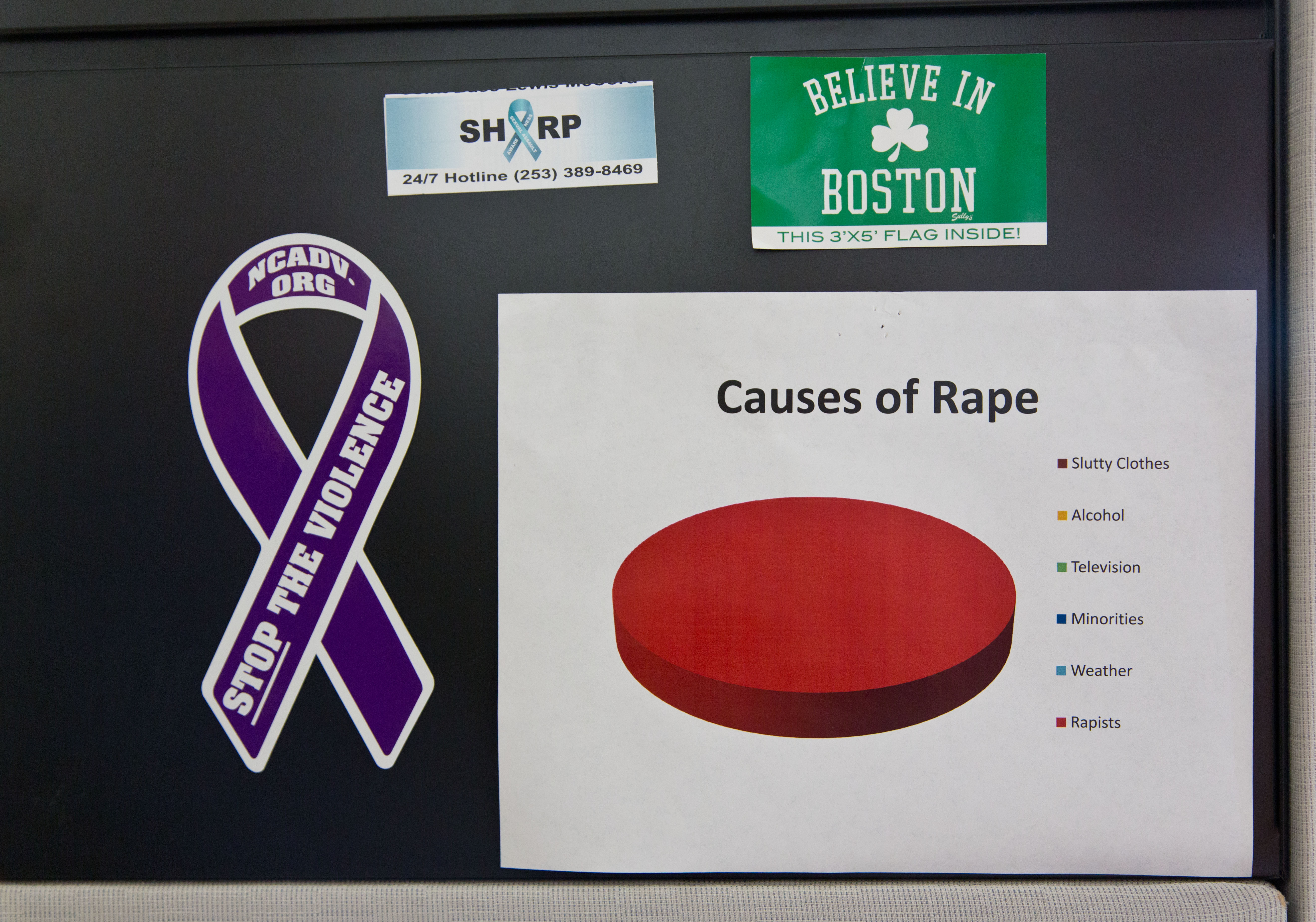

- She now serves as the Soldier Readiness Officer of the U.S. Army’s largest division, the 7th Infantry Division at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, where she also runs SHARP, the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention program established there in 2012.

Not many people, though, know her whole backstory—FlorCruz was sexually assaulted as a 17-year-old college student—because she simply was not ready to tell it.

“I wanted to wait until I’d been in this job a while,” FlorCruz said. “I didn’t want the story of SHARP to be about what I’m about—it’s about the victims.”

But now, FlorCruz will share her intensely personal story at Pacific Lutheran University on Feb. 17 in a public talk titled “From Victim to Survivor to Leader: Preventing Sexual Assault in the Military and on Campus,” the opening event of PLU’s social-justice-themed Spring Spotlight Series “…and Justice for All?”

So why now? And why here?

“I think it’s relevant,” she said. “I was a first-year student at the University of Virginia. My senior RA got help for me. It was Katie Couric—she was just a kid—before she was anybody. But in this audience, judging by what I know of PLU, there’s a lot of somebodies.”

FlorCruz, who is married to JBLM I Corps Deputy Commander Maj. Gen. Kenneth Dahl and has two daughters, said the assaults did not change her career path (though she tried to keep one of her daughters home from college until she was 18)—but they changed the way she went about it.

“When we started SHARP, I think that there was more assault in the Army than when I first came in,” she said. “Our culture is a vulgar culture. We don’t really even know what the rate (of sexual assaults) is—but it is not tolerable, and it is not defensible.”

Sexual assault, of course, is not restricted to the military or to college campuses, but FlorCruz said both institutions’ cultures add particular challenges to prevention.

“We all have the same problem—worldwide, really—but the military and academia share the same demographic: 18- to 24-year-old young people who are away from home for the first time and navigating the world socially,” she said. “They have inexperience with alcohol and inexperience with life.”

In campus communities, said Jennifer Warwick, Victim Advocate and Voices Against Violence Project Administrator for the PLU Women’s Center, first-year students, especially, face challenges learning to navigate a new social life away from family or known support systems. “PLU has many ways in which it equips students to manage high-risk situations, such as educating incoming students about campus norms and expectations around alcohol and sexual consent, while also focusing sexual-assault prevention efforts on addressing perpetrator behavior and empowering bystander action,” she said.

In the military, reports of sexual assault increase when soldiers return from deployments and/or training—FlorCruz calls that “operational tempo”—and one of her SHARP staffers says that concept applies to colleges, too.

“There’s an initial decompression when people tend to act with less discipline,” said 1st Lt. Katherine Rowe, deputy program manager. “It’s event-driven, and people are more vulnerable (in these situations). There’s no alcohol when you’re deployed, so we’re helping people realize you don’t have to drink an entire year’s worth today.”

The relationship between alcohol use and sexual assault is complex on college campuses, Warwick said. “In college environments, alcohol is often used by perpetrators as a tool to facilitate sexual assault by increasing the vulnerability and diminishing the capacity of victims,” she said. “Perpetrators of sexual violence are often less intoxicated than their victims, consuming alcohol at a lower rate (or not at all) in order to maintain the control to manipulate the situation to their advantage. This challenges commonly held societal notions of ‘the drunk guy who lost control.'”

Lt. Col. Celia FlorCruz, left, in the SHARP office at JBLM with staff members, from left, Sgt. 1st Class Timothy Johnson, 1st Lt. Katherine Rowe and Capt. Emily Haynes. (Photo: John Froschauer/PLU)

SHARP at JBLM

SHARP, the first program of its kind, is an Army-required comprehensive program that centers on awareness and prevention, training and education, victim advocacy, response, reporting and accountability as it aims to “eliminate sexual harassment and sexual assault by creating a climate that respects the dignity of every member of the Army family.”

At JBLM, that means SHARP is housed in a nondescript manufactured unit where victims—or anyone who needs help, really—enter through the back door. Inside, FlorCruz, the first officer brought in to head the program, and her staff work to prevent sexual assault and to help its victims—with some innovative approaches that she says could benefit campuses, too.

“We have Special Victims Counsel, attorneys only for the victims; trained senior sexual-assault advocates; medical people specially trained for sexual-assault response; the Army’s largest Special Victims Unit investigations team is at JBLM; and relationships with not just the military but also local police—that’s a model to share with academia. You don’t have to have SVUs at PLU; Campus Safety doesn’t have to be all ‘peeped up.’”

Another shared trait: the vital role of education. Capt. Emily Haynes, division program manager, calls it the biggest part of prevention. “For 18- to 25-year-olds, we offer knowledge of safe practices and procedures—like a ‘battle buddy.’”

The battle metaphor applies in SHARP’s situational-awareness training, too.

“We take (soldiers’) training for detecting IEDs and use that to help them pick up environmental cues for sexual assault and how to intervene,” she said—and then those who intervene are rewarded. “Instead of feeling like you’re a narc, we’re putting a value on acting.”

SHARP also trains Sexual Assault Response Coordinators (SARCs) across all units, carefully choosing and vetting those with whom people feel comfortable before an incident.

“In a Stryker brigade of 1,500 people, one Sgt. 1st Class tanker made himself part of the landscape,” FlorCruz said. “Because he blends in so well, people feel comfortable approaching him. That’s been especially successful in getting male victims to report.”

If that seems like a lot of training and education in an institution known for intense training and education, it is, and FlorCruz said there indeed has been some pushback. “It does seem like we train the crap out of people,” she said. “It should be natural—suicide prevention, vehicle maintenance—we should do it how we do everything. But the military has made an enormous amount of progress. We are utilizing all ranks, all colors, all genders, all different levels of experience, all temperaments and getting perspectives from all demographics—if you look at all our victim advocates, it’s the United-freaking-Nations.”

About the event

Who: Lt. Col. Celia FlorCruz: “From Victim to Survivor to Leader: Preventing Sexual Assault in the Military and on Campus,” part of PLU’s Spring Spotlight Series “…and Justice for All?”

When: 6 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 17. Public reception follows.

Where: Karen Hille Phillips Center for the Performing Arts, PLU campus.

Admission: free and open to the public.

Event registration: Please RSVP for the event.

For more about the SHARP program at JBLM: click here.