Students from PLU and Tacoma’s Lincoln High School work together to fight racism

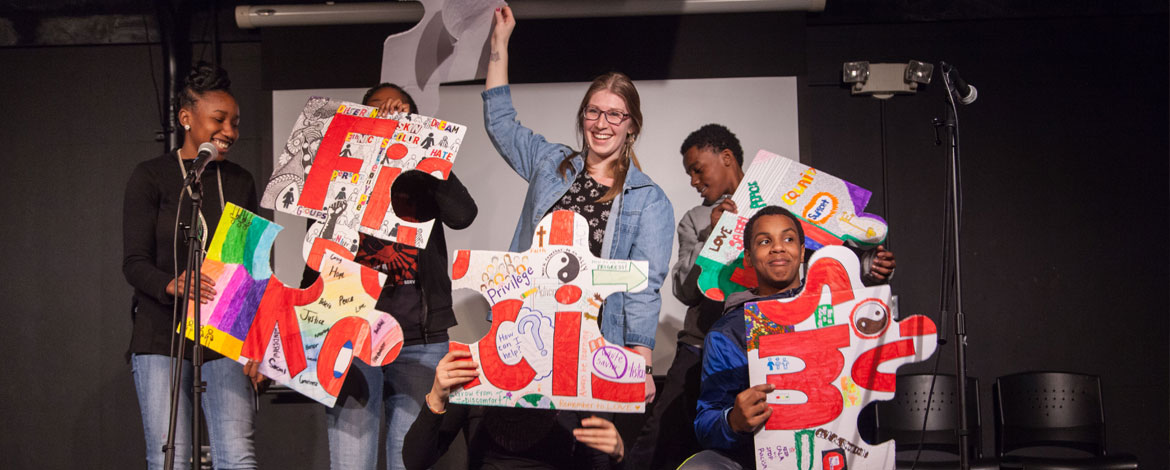

Image: A group of PLU and Lincoln High School students present their hand-made puzzle project titled “Keep an Open Mind” in The Cave. (Photo by John Froschauer/PLU)

By Kari Plog '11

PLU Marketing & Communications

TACOMA, WASH. (Feb. 4, 2016)- Kamari Sharpley-Ragin reluctantly admits that he used to joke about racism. The ninth-grader from Lincoln High School in Tacoma says it didn’t seem like a big deal, since he never really experienced overt discrimination himself. Now, he says he knows better.

“If you’re making jokes about it, people will think it’s funny,” Kamari said. “Then that will spread the problem rather than spreading awareness.”

Kamari’s pivot in perspective was spurred by a monthlong interactive partnership with Pacific Lutheran University and its students who are committed to social justice.

The January Term history class “Fighting Racism in the United States 1896-2016” paired PLU students and teaching assistants with a self-selected group of students from Lincoln grades 9-12.

The workshop-like course challenged them all to critically think about daily experiences with institutionalized racism and how to effectively confront those experiences.

The class touched on civil rights history, as well as racially charged issues today.

The students’ work culminated in an end-of-term “creative extravaganza,” in which groups presented visual representations of racism and how to fight it.

PLU students also cultivated a handbook called “AWAKE: A Handbook on Fighting Racism” that will be distributed to all participants by the end of February.

Kamari, reflecting on what he learned over the four-week course, sat in the high school cafeteria days before the big performance diligently tracing block letters that spelled “equality” on a giant puzzle piece for his group’s project titled “Keep an Open Mind.”

“We’re making a puzzle that represents what would be needed to fight racism,” Kamari said.

Another piece featured a sea of white faces accompanied by the word “privilege,” something PLU student Maya Perez said her peers had to be mindful of while interacting with the local high schoolers.

The senior sociology major said student leaders, such as herself, hosted a training to teach fellow PLU students how to be allies and and not “college-educated white saviors.”

Perez said she was impressed by the depth of participation from the Lincoln students.

“I think the high school students have a lot to teach the college students,” she said.

Fellow teaching assistant Quenessa Long, a sophomore anthropology and political science major, agreed.

“It’s not a top-down mentality,” Long said. “We’re definitely in a privileged position that these students aren’t in. It is definitely humbling.”

Courtney Gould said the course pushed students to apply what they learned in a very intentional way.

“We were hoping that there would be a lot of learning back and forth,” Gould said. “If you don’t leave the PLU dome, you’re not going to have these experiences.”

CONFRONTING PRIVILEGE

Professor Beth Kraig said pushing students to confront their privilege was pivotal to the course’s design.

That included requiring students to ride Pierce Transit buses ‒ either Route 1 or 45 ‒ to and from Lincoln for the weekly workshops.

Students were encouraged to observe and interact with riders and write about their experiences. Those reflections will be included in the final handbook.

“Many of them had never ridden public transit at all,” Kraig said of her students.

The bus passes were free for students; some of the proceeds came from the provost’s Innovative Teaching Grant, reserved for faculty members with spur-of-the-moment ideas or out-of-the-ordinary methods that promise improved instruction. The rest came out of Kraig’s own pocket.

The class and partnership were brand new, and Kraig said she couldn’t have done it without the four teaching assistants.

The idea for the course was sparked by a desire to capitalize on the energy surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement and other social justice campaigns at the forefront of society today, Kraig said.

“It’s a constant look at 2016, but also looking at the past,” she said.

Princess Reese, a Lincoln teacher and 2014 PLU graduate, advertised the collaboration school-wide. Interested students volunteered for the elective experience.

Reese said she’s been proud of how the younger kids have challenged the college students, at times offering them a humble reminder of their privilege.

“They’ve been the ones to consistently contribute,” Reese said of the ninth-graders. “The level of maturity I’ve seen from (the students) has been unparalleled.”

During the workshops, many said it became clear that the Lincoln students shared similar experiences of discrimination, but they didn’t know the language for building a dialogue around them.

Those experiences included students of color feeling that they are held to different standards than their white peers and being treated as though they don’t speak English well based on their race.

CURTAIN CALL

Maria Cruse, another senior teaching assistant majoring in women’s and gender studies, said the J-Term course was “an act of service,” not just a standard learning opportunity.

“I enjoy being a social justice educator,” Cruse said. “This was another platform to do that.”

Many of the students were eager to tell their stories, she said.

They did so in front of a crowd on PLU’s campus, at the university’s entertainment venue, The Cave.

When performance day arrived, groups bustled around The Cave, munching on brain food and preparing their presentations.

Some students sunk into cozy couches to calm their nerves, while others played spirited games of foosball.

PLU students Joanna Morales and Abby Stringer sat quietly, reflecting on their upcoming performance – emotional pre-recorded audio interwoven with poetry and live reflections of identity.

Morales, a first-year, said she took Kraig’s course because it offered a contemporary look at longstanding racial issues.

“We fool ourselves thinking that racism is no longer in existence,” said Morales, who learned different ways to be an activist in the course.

Stringer, a senior, said she realized that she was ignorant to racial issues as a privileged white woman before enrolling in the J-Term course.

“I wanted to learn some facts to talk about it with my family,” she said.

Students’ final performances ranged from poetic to comical; all addressed serious, complex issues.

The atmosphere in the room rapidly shifted back and forth from energetic to somber ‒ an energetic will to spread equity and a somber recognition that society still has work to do.

One skit showed a black man on a crowded bus; passengers wouldn’t sit next to him.

The scene shifted to a classroom where white students asked the new black kid why he doesn’t play basketball or football.

“If you don’t play sports, you rap right?” they presumed.

Another performance demonstrated the difficulty of starting conversations about difficult topics related to race:

“I’m a straight white guy, who wants to talk about racism?!” one participant exclaimed. “I have plenty of black friends, I’m not racist.”

“Seriously?” a poster in response read.

A poetry slam intertwined images of racial epithets and stereotypes with monologues about injustice.

The large, hand-made puzzle made by Kamari’s group included several pieces depicting individual experiences with racism that, when combined, created a unified vision for how to combat those problems.

Following the presentations, the audience roared with applause.

Reese, the Lincoln teacher, praised the group for progress made in such a short period of time.

“It’s been invaluable to watch you grow,” she told them.

Kraig acknowledged that the interactions were fun and rewarding for the students. However, the seriousness of the subject matter wasn’t lost on anyone.

The documentaries shown in class eliminated the sugar-coated understanding of racism in America, she said, and helped students realize what the struggle was truly like for people of color.

“There have been moments I’ve seen people in tears from what they saw,” she said.

Moving forward, Kraig hopes this class or one similar to it will continue.

“I want to make sure what we’re doing is not forgotten,” she said. “You have to do the work now to make the future.”