PLU students study Beyoncé, starships and Holocaust artifacts as part of eclectic fall curriculum

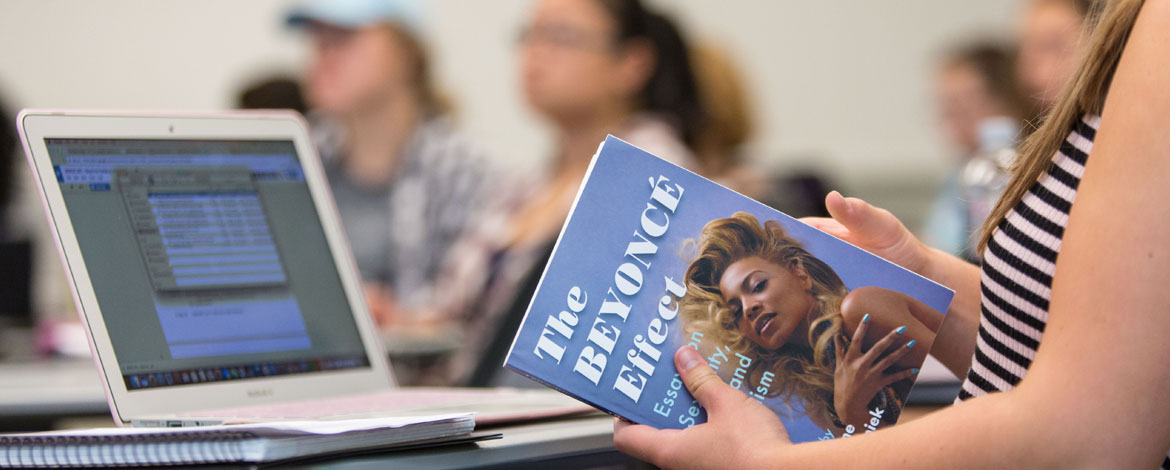

Image: Students study Beyoncé and black feminism in one of many interesting courses offered this fall. (Photo by John Froschauer/PLU)

By Genny Boots '18

PLU Marketing & Communications

TACOMA, WASH. (Sept. 15, 2017)- Pacific Lutheran University students are people of many interests. This semester, several courses illustrate how the university's curriculum caters to those eclectic interests.

Beyoncé and Black Feminist Theory

“Who Beyoncé is for?” is not usually a question that you ask when you’re bopping your head to “Single Ladies,” or “Partition,” or any of the other hundreds of hit songs that have made Beyoncé a worldwide music icon.

But it is just one of the questions students will tackle in the Women’s and Gender Studies course titled “Beyoncé and Black Feminist Theory.”

“The general premise of the course is to think about Beyoncé as a social, political and cultural figure through the lens black feminist theory,” said Jennifer Smith, director of the Center for Gender Equity who will serve as PLU’s first dean for inclusive excellence starting in January.

Smith will be co-teaching with CGE Outreach and Prevention Coordinator Tolu Taiwo.

“It’s going to be fun to co-teach together and engage students to ask really big questions about race, gender and sexuality through something we consume and enjoy,” Smith said.

Students will be studying Beyoncé based around her 2016 visual album “Lemonade.” The first half of the course will be her work pre-Lemonade, and then the rest of the course will be solely focused on the album.

The course uses Patricia Hill Collins’ text Black Feminist Thought, with additional readings written only by women of color. Discussion themes will include marriage, intimate relationship, family, body, and sexuality and empowerment.

The inspiration for the course came from the success of PLU community watch parties and discussions based around “Lemonade” and the 2016 album “A Seat at the Table” by Beyoncé’s sister, Solange Knowles.

“Because we’ve seen these discussions done well with a lot of interesting conversations especially surrounding black feminism,” Taiwo said, “we decided to create a course.”

One of the initial challenges for Smith and Taiwo will be to subdue students who are super-fans of the music.

“I want students to take pop culture seriously as political texts,” Smith said. “Really thinking about issues of identity and power within our pop culture texts is a significant skill for students to have. Will it get you a job? Maybe not, but it will leave you a more informed and aware citizen.”

How to Build a Starship

Spoiler alert: “How to Build a Starship” is a course that’s not really about building a starship.

This yearlong course at Pacific Lutheran University engages students in a thought experiment on how to build and live on a starship for a journey to Proximus Centauri — our star’s closest neighbor.

The fall section of this course will be taught by Daniel Heath, associate professor of mathematics. Students will have to consider questions such as: what should the starship look like, how to create artificial gravity, how many people are optimal for procreation and re-settlement and what a sustainable biosphere might look like.

“It’s not a science course,” Heath said. “It’s a liberal arts course with some science-y themes.”

“How to Build a Starship” is a part of the pilot Cornerstones Program at PLU. Cornerstones offers a cohort-based liberal arts curriculum, in which students take a sequence of linked courses their first two years, and then five additional courses of their choosing across the university to complete the program. “How to Build a Starship” is a second-year experience class, so the same students will take the fall and spring sections.

The second section of the class will be taught by Scott Rogers, assistant professor of English.

“So we have this ship, presume it’s actually built,” Rogers said, “and now we put people on it and so how do they live?”

This section of the course will look at things such as the human experience and how government, vocation, community development and religion would be represented on board.

“This is course where you have to come to terms with diversity,” Rogers said. “You can’t escape it. Social justice, you can’t escape it. You can’t privilege your way out of it, because you are stuck in this context.”

This course will attempt to cover a huge amount of knowledge, a feat that Heath and Rogers are acutely aware of.

“I am a little terrified too because I know if i had to design a starship it would fail pretty quickly,” Heath quipped. “But at least I know the questions to ask and I know where we can start looking. And that is the point. To consider big questions, not really build a starship.”

The Holocaust in the American Literary Imagination

This year, Professor of English Lisa Marcus will do something different with her class, “The Holocaust in the American Literary Imagination.”

Along with readings, literary analysis and the other trappings of a literature course, students will work with historical artifacts from the Holocaust.

“To engage in the material,” Marcus said, “I think one has to do other things than just engage in literature.”

The course is an exploration into the connections between literature, artifact, memory and empathy. Marcus has partnered with a Seattle-based museum, the Holocaust Center for Humanity. Several artifacts from the center’s collections will be loaned to Marcus for use in the course.

“That just feels amazing that I can have access to these artifacts and share them with students,” Marcus said.

The course will consist of critical readings of texts from Holocaust survivors and children of survivors. Students will examine the Holocaust within fiction, asking questions such as “how should the Holocaust be represented?” and “who gets to tell those stories?”

While students are reading the literature, they will interact with artifacts. The goal is to deepen understanding and foster empathy from students about the trauma. This idea is based off a theory called prosthetic memory, developed by Alison Landsberg. As Marcus explains, this is a way for strangers to connect to the Holocaust in a deep way.

“Prosthetic memory is a memory of an event they never experienced but that is made real to them in the curated space of the museum,” Marcus said. “The past becomes accessible, personal, and present.”

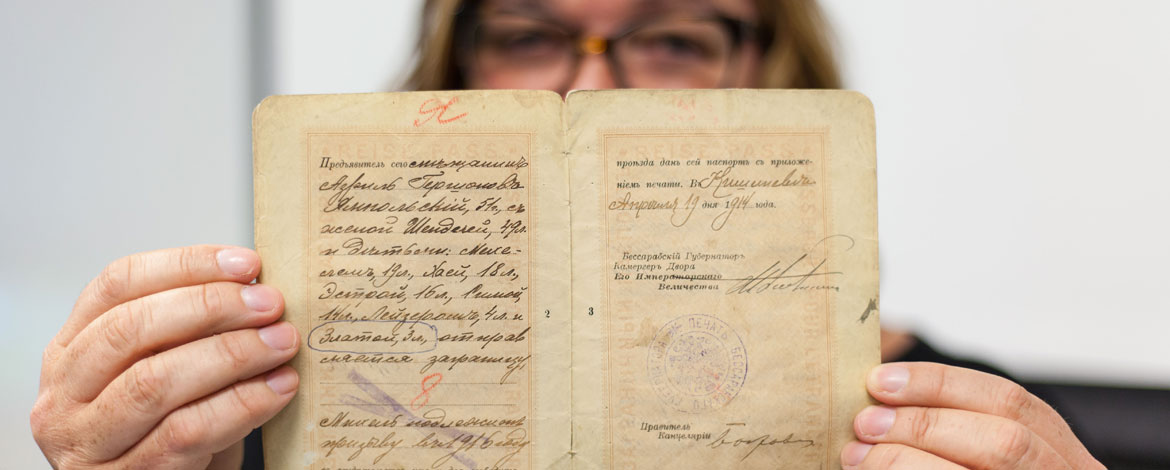

And Marcus knows firsthand the power of artifacts. After discovering her grandmother’s Russian passport from 1914, she took a trip to explore her family’s Jewish history, stopping first at Auschwitz in Poland, before traveling to her grandmother’s birthplace in what is now Moldova. The town her grandmother is from, Siroki, translates as “poverty,” she said.

Afterward, Marcus published a poem, titled “I did not lose my father at Auschwitz,” about the experience of visiting Auschwitz with her ill father, a Jew whose family likely would have perished in the Holocaust had her grandmother not come to the U.S. in 1914.

Marcus hopes the students can do their own creative project about the individual artifacts they work with.

“I hope this project is empathy-building,” Marcus said. “And also building a connection to a history and a past that is both far away and is still relevant for today.”