‘Strong link of three’: PLU graduate’s life — suddenly cut short — is remembered through legacy scholarship

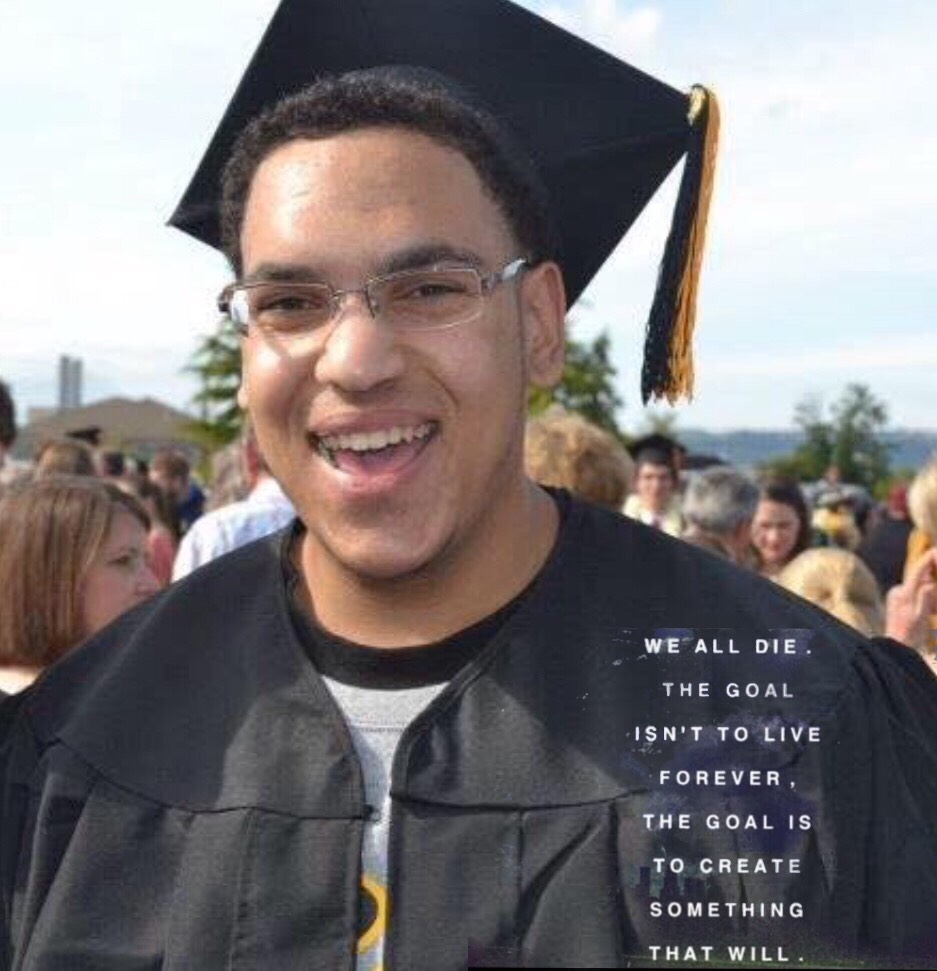

Image: Panayotis (Panago) Horton ’12

By Kari Plog '11

PLU Marketing & Communications

TACOMA, WASH. (Feb. 26, 2018) — Panayotis (Panago) Horton ’12 tattooed a three-link chain on his forearm: one link each for himself, his mother and his brother. The family emigrated from Greece when he was just 2 years old. They were his rock.

And although the Pacific Lutheran University graduate suddenly lost his life last summer, his family says the chain won’t be broken.

“The bond between us remains unmatched,” LeRoy Horton ’03 wrote in a tribute following his younger brother’s death Aug. 22, 2017, due to complications from epilepsy and a subsequent infection at the hospital. “The three of us served as a tight-knit unit to survive life in a strange land.”

But ask anyone, and they’ll tell you Panago didn’t just survive in his new home. He helped make it better.

“He always liked to help people,” Georgia Horton said of her son. “He was a very, very good person.”

At the root of his advocacy was a passion for education. Specifically, access to education for marginalized communities in Tacoma. After graduating from PLU, Panago joined AmeriCorps. He served at Tacoma’s Giaudrone and Jason Lee middle schools, his mother said, both of which educate students from a diverse socioeconomic spectrum.

“He became really involved with the children,” Georgia said. “It broke his heart that some of the students wouldn’t have the school supplies they needed throughout the whole year. He always bought school supplies with his own money.”

The family drew from that passion for Panago’s memorial, requesting attendees donate school supplies and money for school lunches in lieu of flowers or gifts.

But they knew the giving couldn’t stop there.

“When you lose somebody, especially your child — your son, your daughter — you lose yourself,” Georgia said. “The biggest fear that a parent has when they lose a child is that their life was for nothing.”

So, to guarantee Panago’s lasting legacy, his family and friends came together to create a memorial foundation to help local minority high-school students in Tacoma pay for college.

Panago’s Legacy Scholarship, which earned its inaugural funds through an online crowdfunding campaign that exceeded its $5,000 goal, aims to help two or three students each year. Georgia said she’s working with the Tacoma-based program, Ready to Rise, to identify scholarship recipients.

The program is spearheaded by Degrees of Change, an organization that works to extend the reach of the Act Six initiative, which fully funded Panago’s education at PLU.

The awardees — the first of whom will be selected this spring — must embody Panago’s values, including a deep passion for social justice.

“At Degrees of Change, we are honored to support his family by hosting the memorial scholarship they have created to invest in other emerging community leaders who share Panago’s passion and commitments,” said Tim Herron, the organization’s president.

Herron says Panago embodied the Act Six mission, particularly after his time at PLU. He “poured his heart and energy into middle school kids” across the Hilltop neighborhood in Tacoma, Herron added.

“Panago embodied the Act Six mission of homegrown, service-minded leaders working together for equity and justice in their home communities,” Herron said. “There is something profound in watching middle school kids respond to the skilled and caring investment of local leaders who look like them, grew up in the same community, and model every day what it means to love a place relentlessly, even in the face of its pain and challenges.”

His mother stressed that the same commitment to equity must shine through the recipients of the new scholarship; it’s what Panago would have wanted.

“I hope that he’s proud,” Georgia said. “We’re making things happen in his name.”

Jonathan Jackson ’12, a fellow member of PLU’s first Act Six cadre, says Panago possessed an “others before self” mindset. Jackson says his friend wasn’t one to be front and center in his activism and advocacy; he often would “lead from the middle.”

“You might not have known he was involved with something,” Jackson said. “But he was there shaking things up and making things happen.”

Panago fought for social justice, participating in protests and rallies against police brutality. Jackson acknowledged that he and his friend navigated difficult realities together at PLU, a white-dominated space where they dealt with microaggressions from members of the community throughout their educational experience. Still, he says Panago was quick to listen to many perspectives, to carefully and thoughtfully respond with intention.

Angela Pierce ’12, another fellow Act Six scholar from the cadre, says that’s one of the first memories she has of Panago. She recalls being blown away by how pensive he was for a 17-year-old prospective student, during interviews for the scholarship program.

“It was really profound,” she said. “He really made me think.”

And that never changed, she stressed. Pierce says Panago approached everything — at PLU and beyond — with quiet reflection. He was very studious, she added, putting school and family first.

“One of the things I always appreciated about him is that he always valued his education,” Pierce said. “A lot of us in the cadre were similar that way, but out of all us in the cadre he had the hardest major.”

Jackson and Pierce are both involved with the rollout of the scholarships, leveraging their professional knowledge and connections through the organizations Graduate Tacoma and Seattle Education Access. But they play a supportive role, letting the family take the lead.

Panago’s life after PLU was that of self-discovery and transformation, which he navigated in between his selfless causes. The biology major opted to veer from his original plan to become a dentist — something initially inspired by his older brother who went into dentistry. In his final months, he decided to pursue law school and was preparing to take the LSAT.

Panago also embraced healthy living, spending a lot of time at the gym and dropping a significant amount of weight in recent years. Despite his best efforts, his health took a turn in 2013. That’s when he experienced his first seizure, his mother said, the first in a years-long battle with epilepsy.

He started taking medication, Georgia said, but finding specialists, research and other resources was challenging.

Epilepsy is the fourth most common neurological disorder, according to the Epilepsy Foundation. The chronic disorder, which is characterized by unpredictable and unprovoked seizures, doesn’t frequently lead to death. Still, it can cause other health problems — and public perception and treatment of people with epilepsy often create bigger problems than the actual seizures.

At least a million people nationwide suffer from the disorder. More research, better treatment and a cure is in high demand.

Panago started having more frequent seizures around Christmas 2016. It wasn’t until July that his mother was able to help him secure an appointment with a neurologist. The appointment was scheduled for September, just a few weeks following Panago’s last seizure Aug. 14.

“We were unprepared,” Georgia said. “The cards were stacked against him.”

Georgia hopes Panago’s story will raise awareness around epilepsy, and hopefully spark change.

“My biggest regret is that I could have learned so much more beforehand and maybe we would have had a different outcome,” she said.

Panago’s loved ones epitomized his fighting spirit throughout his final days, which were spent in an induced coma. “We did our best to fight for him because we knew he always did and would fight for us,” his brother wrote in his tribute.

They continue to fight each day, with his memory lingering in all they do — from online fundraisers for the Epilepsy Foundation to marches for equal rights.

“We can keep Panayotis Alexandros Horton in our world by thinking and speaking our memories as long as we live,” his brother wrote.

That’s how his family ensures their three-linked chain will never break, and — in Panago’s words — will carry on:

“I am from a strong link of three,” Panago wrote in his “I Am” poem, in a class at PLU in 2008. “From a chain that continues to grow.”