Teaching in the Pandemic: How Three Teachers Made the Best of an Unprecedented Time

Image: Alonso Brizuela ’14, Sarah Lord ’00, Caitlyn Zwang ’09

By Lora Shinn

PLU Marketing and Communications Guest Writer

High school choir and guitar teacher Alonso Brizuela ’14 was in Spokane at a national choral directors conference in mid-March of 2020. Just a day and half days into events, the conference shut down early—due to a mysterious new illness that had arrived in the U.S.

Upon returning home, Brizuela, who majored in music education at PLU, had two in-classroom days with his Clover Park School District students before classes were suspended. “It was a rapid-fire shut down of everything,” he remembers.

Two states away, Sarah Lord ’00 was teaching high school biology and environmental science at Billings Senior High School in Billings, Montana. While inconvenienced by the immediate shutdown, she didn’t realize the scope until several weeks after schools closed.

And thousands of miles away in San Antonio, Texas, kindergarten teacher Caitlyn Zwang ’09 was halfway through spring break when she realized that “something was going to happen,” she says.

It did.

For these three PLU graduates and public school teachers, the COVID-19 pandemic changed classrooms, instruction, and learning. But it also brought new opportunities for teachers and students alike.

Spring 2020: The Virus Arrives

Most U.S. teachers had to get acquainted with Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and other tech—few had used it for everyday instruction. Virtual singing classes were soon on Brizuela’s schedule.

“We were able to explore the music a little bit differently,” Brizuela says. “Last spring was definitely, ‘Let’s figure out how to make the students successful with the limited time and materials that we have.'”

Students could practice research skills and sight-singing and record themselves. Essentially, activities often shunted aside when focused on concert deadlines.

Pandemic instruction was a learning process for everyone in San Antonio, Zwang, who majored in elementary education and Spanish at PLU, said. “April was a disaster, but by May, we started getting back on track,” she says. Her STEM-centered school already had laptops for each child. The district bought hotspots for some families and hotspot-equipped school buses parked in large sports arenas for others.

She loosened expectations for her kindergarteners, many of whom had parents working essential jobs as Amazon drivers, grocery-store workers and nurses. One student was one of 10 children in the family, with a truck-driving father stranded on the road. Another, the child of a nurse, had to live with grandparents for a while.

If a child watched the day’s posted video, Zwang counted that as attendance—as did completing homework over the weekend with an essential-worker mom. Zwang addressed social-emotional needs, too, talking with kids about what the virus meant and that it was OK to be scared.

In Montana, Lord’s classes typically offer hands-on learning opportunities—hatching butterflies, creating composting systems, mealworm experiments—which were abandoned at the pandemic’s start. “Switching from a hands-on, active, physically engaging environment to a screen-based digital platform was hard for the students, and for me,” she says.

While Lord, who majored in religion at PLU, invited students to perform outdoor activities and experiments, most students just didn’t engage. Billings High School is one of Montana’s most economically and racially diverse schools, with a significant disparity in access to technology and the internet. “We lost contact with 50% of students, and it wasn’t for lack of trying,” Lord says.

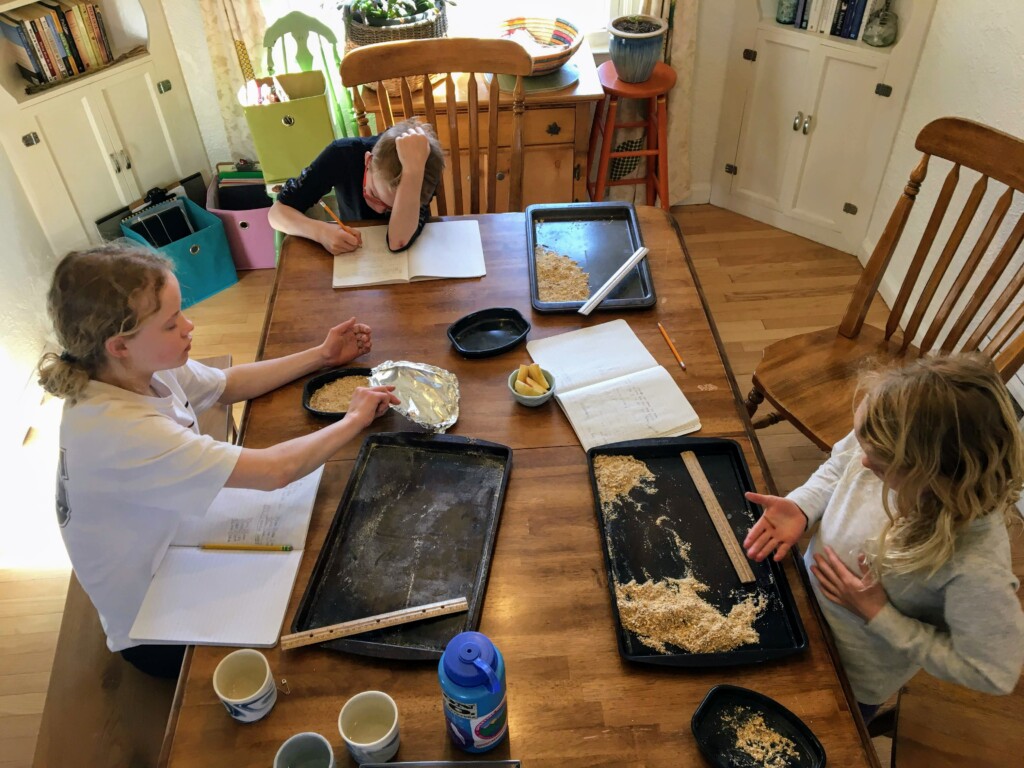

Lord, her middle-school-teacher husband, and their three children, ages 9, 11, and 13, all sat at the kitchen table to get schoolwork done, headphones on. “I was trying to help my daughter with math and respond to the students in my own classes,” she says. “It was such a complete and utter pivot for everyone.”

Summer brought time to breathe for all three teachers. Brizuela and Lord prepared for fall classrooms with virtual options, while Zwang entered a Montessori teacher-training program.

School Year 2020-2021: New Approaches

By the fall of 2020, Brizuela felt more comfortable teaching music in a virtual classroom and encouraging students in conversation and interactions. Although students often turned off their cameras, they could still practice the fundamentals used in rehearsals and music-making.

By spring of 2021, Brizuela’s school entered a hybrid schedule, so students are now in music class one day per week, in person. Due to guidelines around air-exchange rates, the choirs moved into the performing arts center where students can spread out, and choir participants wear “singer masks,” which look a bit like a duck’s bill.

Work tends to be simpler and focused on small groups—even two or three students can comprise a group, using and building on the skills they’ve learned online so far. “They still want to be challenged, and interact with each other,” Brizuela says. “They still want to sing.” After being online for a year, there’s been a learning curve for students who need to rebuild confidence around in-person singing.

In Montana, Lord’s high school students could come back in person or fully remote in fall 2020—but had to stick with their choices for the year. Close to 20% of students opted to stay remote.

At school, longer class periods and week-on, week-off block scheduling was introduced, to reduce classroom and hallway congestion. “As a science teacher who focuses on the outdoors and hands-on activities, I loved this transition to longer class periods,” says Lord. Overall, there was a commitment from parents, teachers and school administration to do what was necessary to have in-person learning again. “We understood how much better off we would be if we had in-person learning.”

Students who’d disappeared from Zoom screens in the spring of 2020 returned to school in fall 2020. The overwhelming student feedback Lord received: It’s easier to learn from an in-person teacher. She missed those face-to-face interactions, too.

In the fall of 2020, Zwang began work at Rodriguez Montessori. Just three children started in the in-person classroom, but more kids phased in gradually, and now, about half of the class attends in-person.

Running both the online and in-person classrooms simultaneously wasn’t as challenging as it sounds, she says. With the Montessori Method, small groups of students are given a lesson in reading or math, usually with hands-on materials. The child practices on his or her own then demonstrates lesson mastery to the teacher before moving on to the next lesson.

Twice per quarter, Zwang sent home kits, and parents could cut out the materials, which the child then used in their teacher-child lessons on Zoom. Students could upload their practice sessions via the learning app Seesaw. In-person circle time involves a robot that holds an iPad, seated amid the students, so the virtual and in-person students can interact.

One challenge: required masks can muffle the sound of letters when teaching reading. Zwang discovered that the online kids benefited from seeing her unmasked mouth, demonstrating the difference between a “p” and “b” sound.

Zwang’s children are only on Zoom for about 30 minutes a day, on average. It’s an intentional decision. Maria Montessori’s journal indicates that new technologies could lead to laziness—and should only be used as a tool. “So that’s the mindset we approached the school year with, using technology as a tool and not a replacement for Montessori class time. Limited screen time is rooted in her writing,” Zwang says.

Living Out the PLU Mission

An education at PLU provided all three teachers with a foundation and resiliency for managing pandemic’s difficulties. Brizuela encouraged camaraderie and community among the high school students, which he learned from PLU’s conductors, such as Richard Nance, Brian Galante and Barry Johnson. He says the differences between online or in-person work aren’t as stark, as long as you can fuel the necessary group dynamic familiar to many musicians.

For Zwang, PLU’s rigorous education major reinforced the importance of the human. “The child is a human before a student, the parent is a human before a school parent. It’s very compassionate and student-centered, focused on the families’ needs, versus data-driven. Kids are more than a number on a page,” she says.

Lord says PLU’s mission around educating for “a life of service” shaped her perspective during the pandemic. “I think it helped me see where students are coming from before making assumptions,” she says. She can understand and empathize if a student struggles to complete a biology assignment when also experiencing food or housing insecurity, providing childcare, or competing for space with five siblings—and no internet access.

“The pandemic was a fantastic eye-opener for the community and country on how important social, face-to-face interaction is in our ability to learn, and the value of in-person education,” Lord says. “Public education is such an important service worth continuing to improve and preserve.”

Next year, remote learning will no longer be an option at Lord’s school. At Zwang’s school, parents will once again choose virtual or in person, and the school will probably hire an online-only instructor for the kids at home. So the circle-time robot may wave goodbye.

As for Brizuela, he’s hoping to see all his students again next fall. “Even if they do turn on their cameras, it’s not the same as being in a room with someone,” he says. “Interactions with people are what I’m looking forward to as we return to whatever is next.”