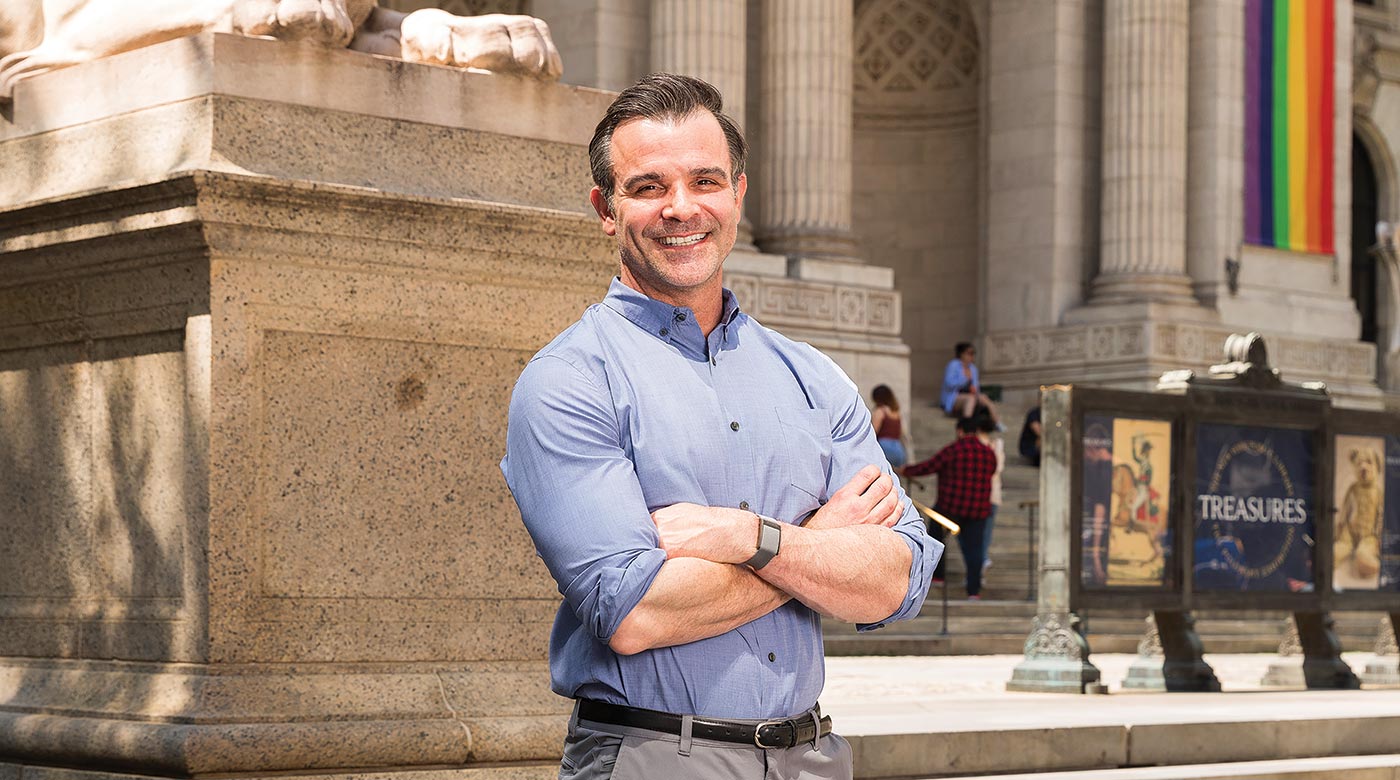

The People’s Librarian: Brian Bannon’s passion for democratizing information led him to the New York Public Library

Image: Brian Bannon ’97, Director of the New York Public Library. (PLU Photo / Sy Bean)

By Zach Powers '10

Resolute Editor

In 1997, Brian Bannon was a PLU senior. An exemplary student, he wrote for The Mast, and was a double major researching social justice through the lens of queer rights movements.

One afternoon, Bannon found himself in the office of history professor Beth Kraig, discussing his plans for the future. He knew he wanted to pursue a career related to social justice and service, and he was considering social work, or perhaps teaching. Kraig asked him a question that changed his life forever.

“Have you ever thought about becoming a librarian?” Bannon was surprised by her question. He loved his local library growing up, but had also struggled to manage his dyslexia and long aisles of books didn’t exactly excite him. Kraig, an American history scholar, explained how libraries have been on the forefront of social justice and play a key role in providing access to knowledge that belongs to everyone.

Kraig shared how, especially early in U.S. history, private libraries represented wealth and power and exclusion, preventing most Americans from accessing valuable sources of knowledge and information. The innovation of public libraries, she said, was foundational to the democratization of education and information.

Bannon left his adviser’s office inspired. “She helped me see that something I was really passionate about could be found in libraries,” he says. “I never would’ve made that connection.” Later that spring, Bannon was accepted into the University of Washington’s Master of Library and Information Science program.

Now, 26 years later, Bannon is the New York Public Library’s first-ever Merryl and James Tisch Director, responsible for directing NYPL’s 88 neighborhood branches as well as the library’s educational strategy. His career in public library administration has taken him across the country, and he’s learned lessons each step of the way that have made him a better librarian, public administrator and education leader.

Brian Bannon gives a keynote talk at a 2016 Aspen Institute-sponsored conference.

An Emerald City mentor

After two years at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bannon began his library career in the Emerald City. He was hired by the Seattle Public Library in July 2000. Within two years, he was elevated from overseeing the delivery of technology instruction to managing the design and launch of three new branches.

Bannon still remembers how then-CEO Deborah Jacobs made a point to mentor him. Jacobs, a legendary figure in Seattle civics and the national library community, is known for leading the passage of a historic Seattle library bond and raising an additional $300 million privately to rebuild or renovate every library in the city.

“I was a very junior person in the organization, but she took an interest in me,” Bannon remembers. “Deborah was a big fancy person in the field, the fact that she cared enough to show interest in me was a really important lesson in leadership.”

Bannon now knows that Jacobs took a similar interest in other young leaders in the organization, motivated by her commitment to developing future leaders in the public library field. Inspired by Jacobs, Bannon now shares this commitment. “A big part of my focus now is thinking about how I can cultivate and support the next generation of leaders in this field, not just for my institution,” he says.

The City that Knows How

At the age of 31, Bannon was named San Francisco Public Library’s chief of branches. He oversaw 300 people and was responsible for all 27 of the system’s neighborhood branches. San Francisco is a richly diverse community, home to a majority non-white population and one of the largest LGBTQ+ communities in the country. Bannon says he was fortunate to inherit a team of community-orientated librarians that reflected the communities they served.

“It was the first time I’d really been in a management job where my team really was of, and knew, the communities that we were a part of,” he remembers. “There were countless examples during that period of time where I had people who had a different lived experience and therefore a unique perspective, and they could help navigate the culture and the politics in a much more nuanced and impactful way than I could have.”

Bannon led a $200 million dollar capital improvement initiative to design, build, staff and open 24 new and renovated branch locations across the city. He understood that distinct areas like Chinatown, Mission District and Eureka Valley would benefit from different library programs and resources.

Bannon directed a community input process where staff at each branch convened discussions with residents about what they wanted from their neighborhood library. The branch improvements resulted in a 40 percent increase in use — an unprecedented result that Bannon credits to the diversity of his staff and their authentic community engagement.

“Of course I understood, intellectually, the importance of diversity and inclusive staff and leadership, but that experience exemplified how it’s not just the right thing to do — it’s also the smart thing to do, and necessary to get the absolute best result.”

Chi-town CEO

In 2012, Bannon was appointed CEO of the Chicago Public Library. Newly-elected Mayor Rahm Emanuel tasked Bannon with revitalizing the 140-year institution.

Chicago, Bannon quickly discovered, was a city still reeling from the Great Recession, desperately in search of innovative solutions to complex problems related to violence, education, food insecurity and housing. The myriad challenges meant that the library system was under fire from other city departments hunting for additional funding.

“I learned relatively early in my tenure that the passion and belief I had in the potential of the libraries wasn’t necessarily shared by the entire ecosystem that I was a part of,” Bannon recalls. “It wasn’t that people didn’t care about libraries, but it was a city with a population and economy the size of many countries — so there was a lot of power and need to navigate.”

“I needed to protect libraries, but I had to feed the beast of the city,” Bannon remembers. “Once I was able to look at things through the lens of the mayor, I realized I needed to convince the mayor and other department heads that the library could be an important vehicle for serving the city.”

Bannon infused design-thinking methodology into all levels of library operations and launched an ambitious and comprehensive five-year strategic plan aligned with Mayor Emanuel’s education and economic priorities. Library programs across the city were reimagined and redesigned. For example, under Bannon’s direction, family summer program attendance at Chicago Public Library grew by 80 percent, and that attendance was linked to a 15 percent increase in reading and a 20 percent increase in math and science performance in school.

As Bannon and his team propelled the Chicago Public Library forward, leaders across the Windy City and beyond took note. During his tenure as CEO, Bannon was named one of Fast Company’s “100 Most Creative People in Business,” listed by the Chicago Tribune as one of Chicago’s top 100 innovators, and selected for a leadership fellowship at the Aspen Institute.

Bannon would become one of the longest serving members of Mayor Emanuel’s cabinet. Not only did he successfully shield the library from budget reductions, he led the system into an exciting new era. “The mayor came in proposing a massive cut to libraries,” Bannon says. “But by the time he left, he saw libraries as being one of the great successes of his mayoral tenure in Chicago.”

Big plans in the Big Apple

What motivated Bannon to accept his current role as Merryl and James Tisch Director at the New York Public Library was the organization’s commitment to research and education. In addition to having 88 neighborhood branches and the largest circulation in the country, NYPL is the world’s largest public research library and works extensively with New York City Public Schools. “It’s actually three different types of library all rolled into one,” Bannon says. “There’s nothing like it.”

NYPL is a world-class collecting institution, but its access philosophy is different from many peer organizations with similar collections. “It’s wonderful that private institutions like Harvard, Princeton and Yale have amazing libraries, but in order to get behind those walls you need to be affiliated with those universities,” he explains. “At NYPL, we spend millions of dollars a year the way that museums do, acquiring collections in order to make those collections available to everyone and anyone with a library card.”

As the Merryl and James Tisch Director, Bannon is the chief librarian and reports to the CEO. He’s also tasked with developing and leading all of the education programs in the branches and the library’s four research centers. “I lead the part of our business that functions as the public circulating library, while I have a colleague who leads our research libraries,” he explains. His face lights up when he shares about a new program called the Center for Educators and Schools that has been established under his leadership.

Inspired by work being done by his colleagues at the Schomburg Center for Black Culture Research, one of NYPL’s four research libraries, the new center is working to integrate NYPL’s collection of primary source materials into K-12 schools across the five boroughs. The center hired 30 educators to design curricula that incorporate materials from the library’s extensive archive of original letters, newspapers, works of art and other historical materials.

“It’s particularly powerful today, especially considering debates around critical race theory or what’s considered true history,” Bannon says. “Primary source documents on their own can tell a really powerful story that doesn’t have to be my opinion or your opinion.”

The center is just one example of a portfolio of innovative initiatives Bannon is leading in New York. It’s also an example of the impact proposition that Professor Beth Kraig once presented to him in her office. Public libraries, his academic adviser told him, could be a catalyst for the democratization of education and information. Little did she know back then, her advisee would become one of the country’s most innovative, impactful and successful public librarians.