Healing Vocations: Studying Religion and Healing at PLU

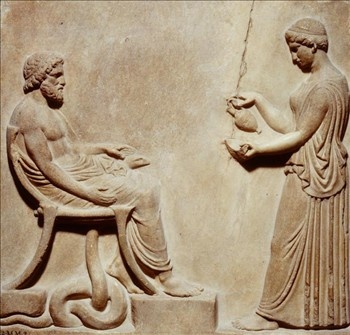

Sometimes being sick isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. In fact, what it means to be sick — or to be healthy for that matter — might surprise us. As the growing field of Religion and Healing shows, our understanding of what it means to be healthy, how we experience illness, and how we work to get well is shaped by our culture, our religious tradition, and our moment in history. It’s not just PLU faculty who are saying this: increasingly, medical schools and public health graduate programs are recognizing the importance of professionals who understand diversity and spirituality. In fact, many medical and nursing schools now advise that practitioners take not only a medical history of incoming patients, but also a spiritual history as well.

Such shifts in the medical marketplace helped inspire a new set of courses at PLU. During the 2015-2016 academic year, the Religion department will be offering a new set of linked courses: Religion and Healing in Comparative Religions (Fall 2015, taught by Dr. Suzanne Crawford O’Brien) and Health and Healing in Christianity (Spring 2016, taught by Dr. Brenda Llewellyn Ihssen). The courses will be linked, so that the same groups of students will be automatically enrolled in the second course. This will not only foster consistency and camaraderie, but also ensure that students will fulfill both their Christian Traditions and their Global Religious Traditions requirements through this thematically unified pair of courses. Priority will be given to students who have declared or intend to pursue careers in medicine, counseling, hospital chaplaincy, or other healing traditions.

Llewellyn Ihssen’s course (RELI 227) will explore the ways in which illness and healing have been understood within the Christian religion, from the earliest days of the Jesus movement to the contemporary era. As these courses make clear, sources of illness, approaches to healing, and ways of making sense of death have changed in the history of Christianity. Biblical narratives of Jesus healing the sick, the lives of medieval saints known for their miracle cures, religious orders that founded hospitals and missions for the poor, Pentecostal faith workers, twenty-first century support groups for recovery from addiction; all understand wellness and healing in different ways, and all are linked by their foundation in the Christian religion.

Looking at religion and healing from a comparative perspective, Crawford O’Brien’s course (RELI 230) invites students to consider how illness, healing, and wellness are understood and experienced in traditions outside of mainstream Christianity. This course explores how wellness has to do with the ability to maintain a working identity: a self that can participate in the give and take of society. Here, wellness is understood to involve the whole person, encompassing physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing. By considering a wide variety of healing traditions, such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, Dine (Navajo) healing traditions, Jewish healing movements, Ayurvedic medicine, or the practice of Curanderismo within Hispanic communities in the United States, the course challenges classic biomedical assumptions that health and wellness are static, universal categories that describe a physical body in proper working order. Instead, students begin to see that effective healthcare within a diverse society needs to address the whole person, and must be adapted to be culturally appropriate and spiritually relevant for the individual patient, their family, and their community.

PLU has a remarkable record of producing highly respected nurses, and of seeing our pre-med students accepted into medical school. But it is not just our academic rigor that makes PLU an ideal place to prepare for work in the medical field. One of the things that makes PLU such an exceptional place is our foundation in the Lutheran tradition, which challenges us to explore the vocation of healing — rather than the profession of it — and to think about healing the whole person in the context of their own community.

— Suzanne Crawford O’Brien and Brenda Llewellyn Ihssen