Personal Journey

I entered Pacific Lutheran University in 2007 as a first-generation college student who grew up void of a faith tradition. I never really struggled with my lack of religious identity.

As recent as six months before graduating high school, it didn’t cross my mind that I’d attend PLU. I was a Spanaway native who always assumed the “L” excluded me from consideration.

Then I toured campus and stayed overnight. I learned PLU’s middle name wasn’t a label, but rather a philosophy — a philosophy that energized me. I didn’t have to be Lutheran. The Lutheran in PLU means “come as you are, leave a better version of yourself.”

I returned to the university in similar fashion earlier this year. An unexpected vocational shift landed me in charge of a magazine showing others the value of Lutheran higher education — the commitment to big questions, inclusion and thinking within and beyond yourself that fundamentally changed who I am.

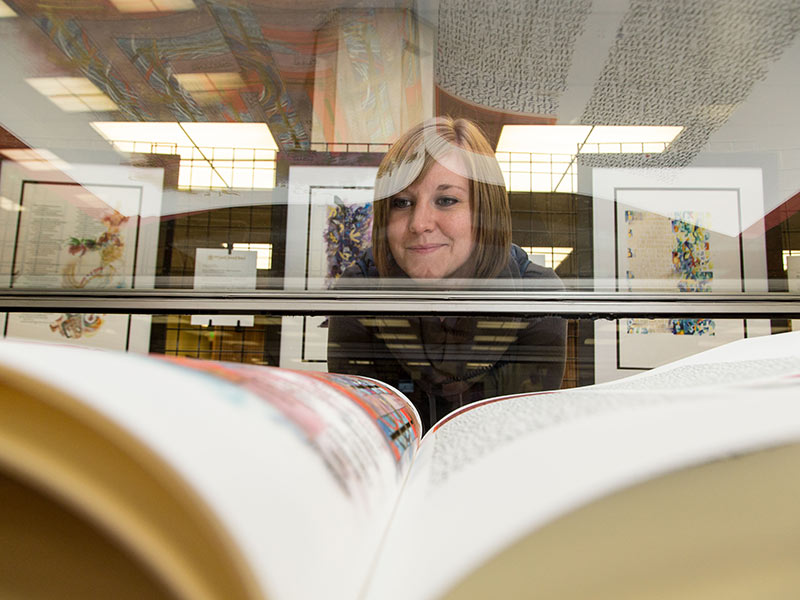

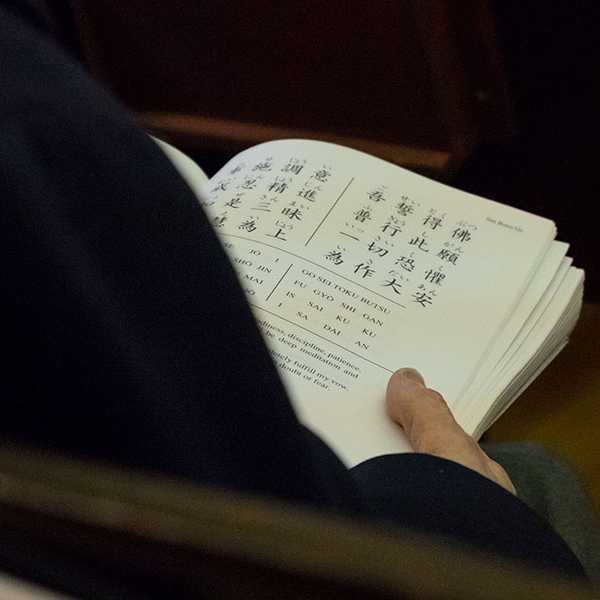

I still don’t identify with a faith tradition, and yet I’m here writing a story about an illuminated, handwritten Bible that inspired me from the moment I first examined its pages in Collegeville, Minnesota.

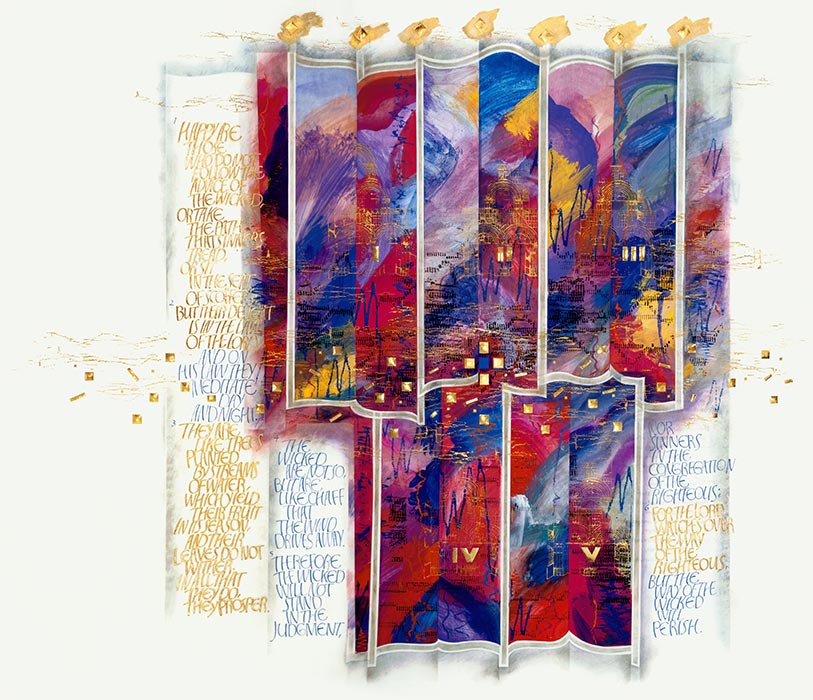

The Saint John’s Bible captivates me for the same reasons I was pulled to PLU. It’s beautiful. It’s accepting. It’s a vehicle for bringing people together to ignite collective spiritual imagination, to reflect on what matters most in the world.

My journey with PLU is not a journey of faith or lack thereof. It is, instead, a journey of embracing the values of Lutheran education. I am a champion of those values for the same reasons I am a champion of The Saint John’s Bible.

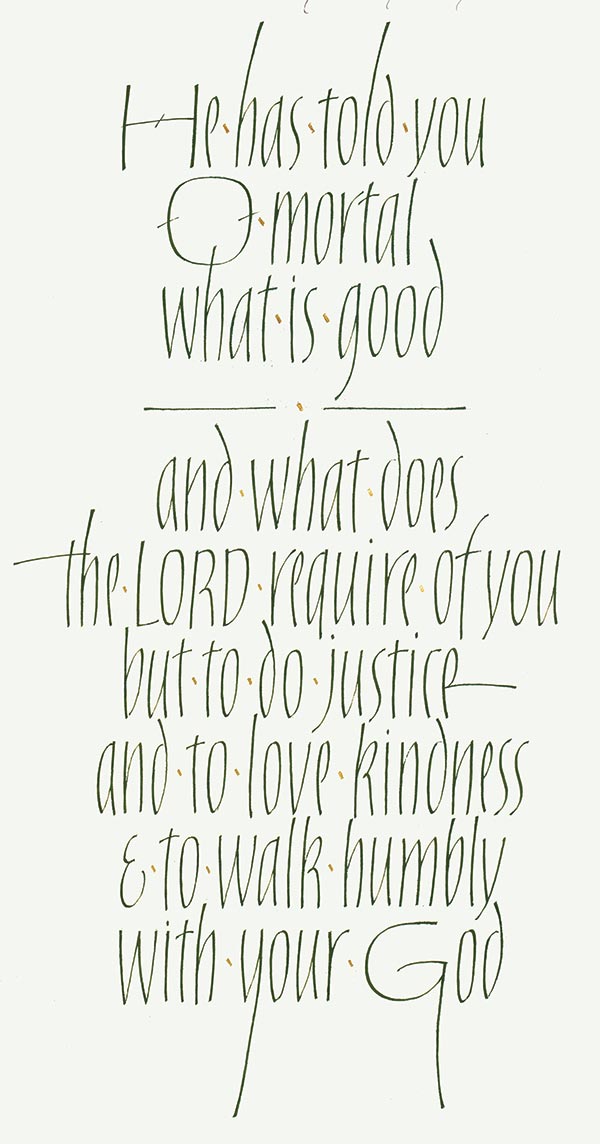

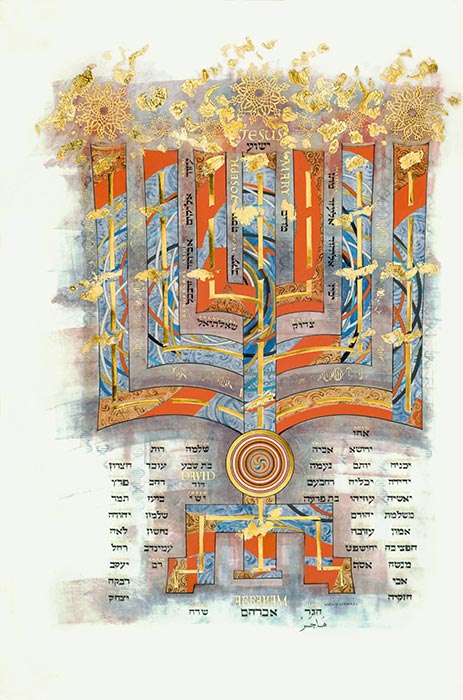

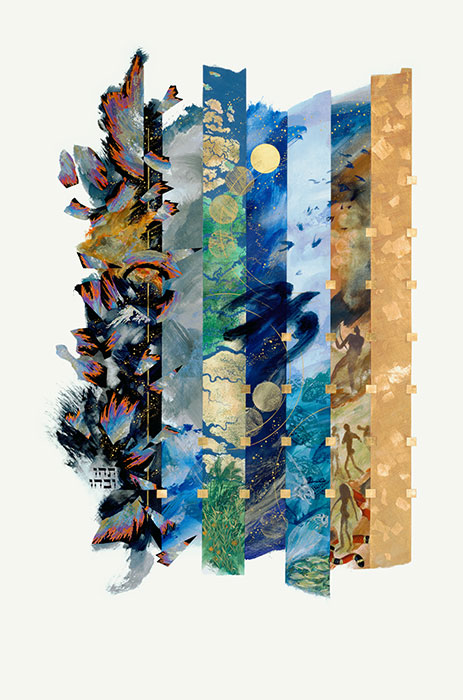

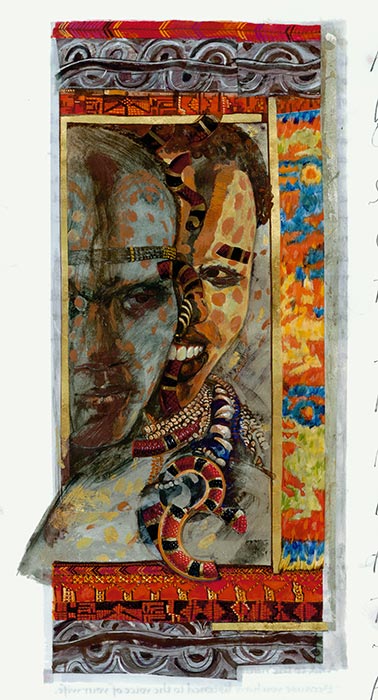

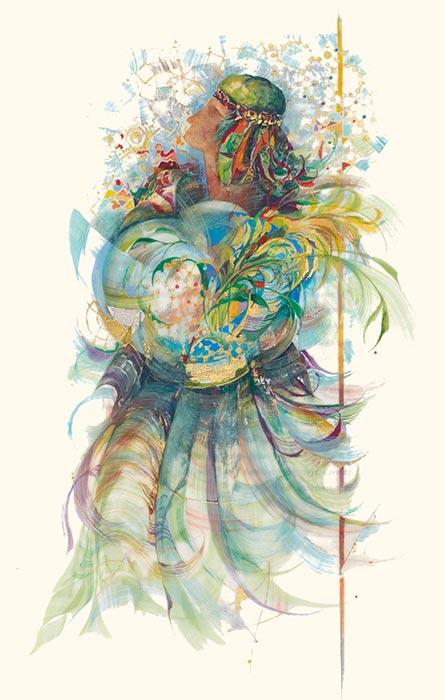

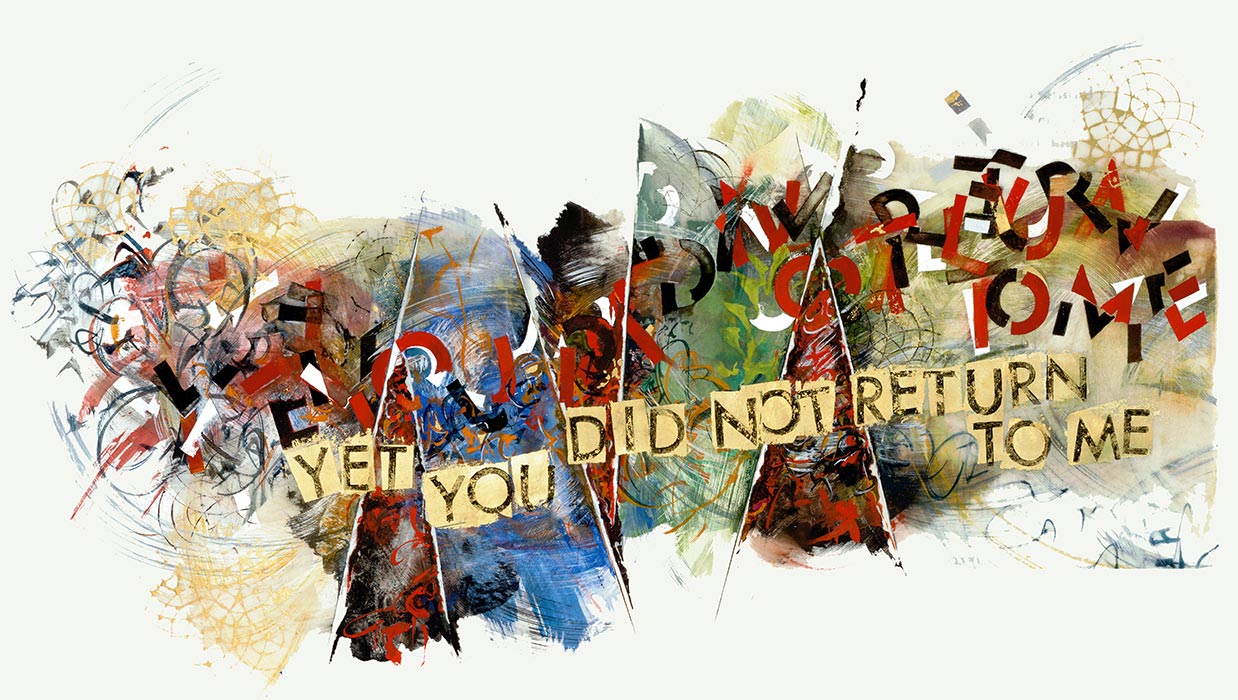

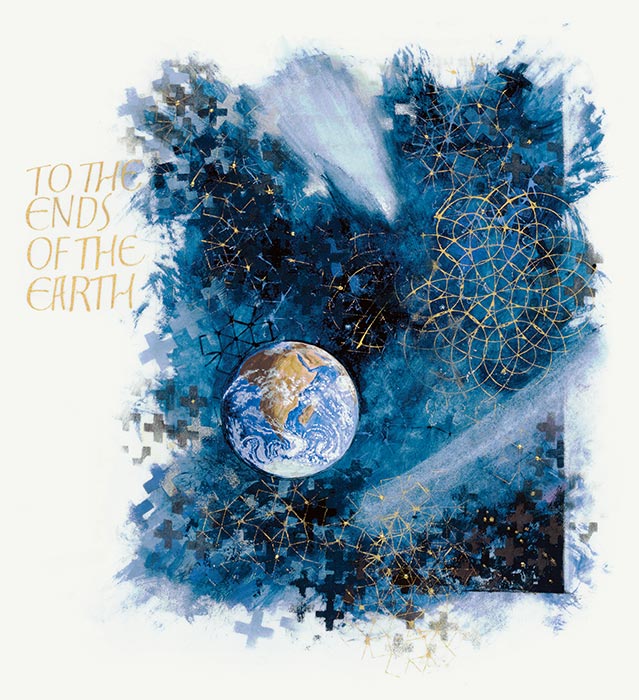

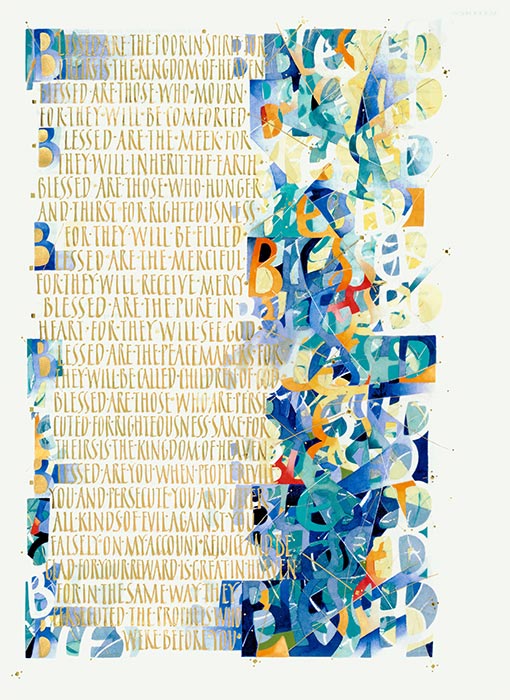

My story about the Bible describes its creation, purpose and connection with those who interact with it. The stories that follow embody the intersection of the book’s primary themes — hospitality, transformation and justice for all people — with the core tenets of Lutheran education. Each themed story is paired with an illumination from The Saint John’s Bible, as well as a related Martin Luther quote.

So, while I’ve never been profoundly affected by any religious traditions, I continue to embrace PLU’s middle name religiously. Once you learn more about the values that prop up the middle name, I believe you’ll embrace it, too.