University builds up to monumental anniversary with Re•forming series honoring Lutheran higher education

Martin Luther, a humble German theology professor and Catholic clergyman, seemed an unlikely man to start a revolution. But when he questioned the Catholic church’s practice of selling indulgences in his famous Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, it was the beginning of an era of religious and political upheaval that would fundamentally reshape Europe.

Luther’s challenge against the church, arguably the most powerful institution in the world at the time, was a bold statement. Since then, Lutheranism and the idea of reform have gone hand in hand. For many Lutherans, reformation is a constant process that continues to this day.

Pacific Lutheran University has long embraced a commitment to introspection. The university plans to bolster the philosophy of reform as it marks the upcoming 500th anniversary of Luther’s historic defiance.

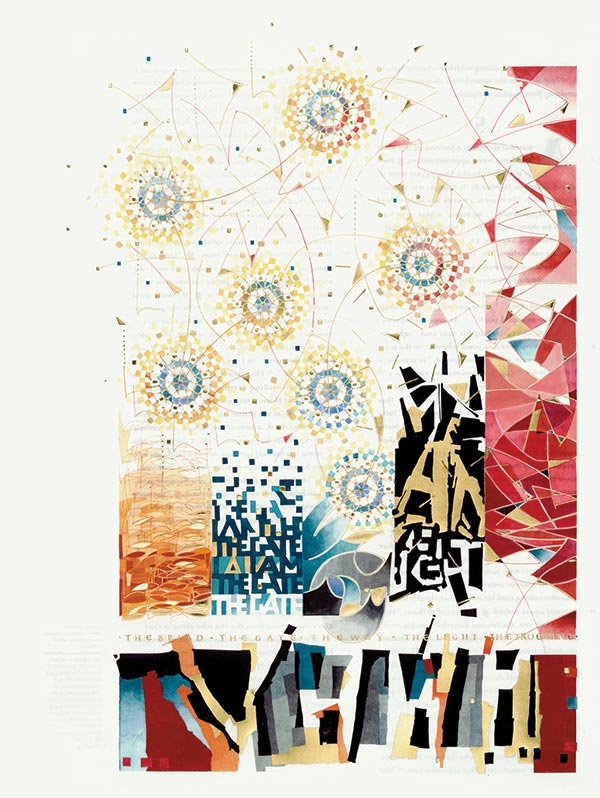

PLU’s year of reflection, Re•forming, will offer sweeping events that will culminate in October 2017, five centuries after Luther started his revolution. Lectures, exhibits, concerts and more spanning the next year will allow the campus community and beyond to reflect on the importance of reforming, which is the foundation for the core tenets of Lutheran higher education.

Those elements, a longstanding part of the fabric of the PLU community, will adorn banners greeting campus visitors to share in the celebration. Visitors, students, faculty and staff also will get to learn more about Luther through interactive geocaching. Thanks to the work by sculptor Spencer Ebbinga, associate professor of art and design, 21 miniature Luther statues hidden across PLU’s campus in October will ping phones and offer fun facts about the historic theologian.

All of the engaging events, including some that have yet to be determined, will build up to the milestone anniversary on Oct. 31, 2017, allowing a community to reflect together on a movement that continues to shape our values today.

Challenging Authority

Though he had the greatest impact, Luther was not the first to challenge the authority of church leaders. Samuel Torvend, Ph.D. and chair of Lutheran studies at PLU, explained that Luther’s native Germany was already a hotbed of discontent, with many Germans increasingly frustrated with church practices.

Torvend said Luther’s path to revolution started with a personal quest to find answers to his own questions about salvation and damnation. He would frequently ask his religious superiors what he needed to do in order to be with God in the afterlife.

“That really kind of drove him crazy,” Torvend said. “On the one hand he’s told he can do all these spiritual activities and the more you can do the better, but no one could tell him how much he needed to do.

“The personal anxiety led to the questioning, and the questioning piqued when members of his parish in Wittenberg, Germany, had gone across the river to another province in which spiritual favors were being sold.”

According to the Vatican, these “spiritual favors” — indulgences — would ensure that the people who paid would spend less time in purgatory.

Torvend said Luther saw two problems with paying indulgences: it discriminated against the poor and was nowhere to be found in the Scriptures.

Both these economic and theological questions prompted Luther to craft The Ninety-Five Theses — a direct opposition to the practice that he considered abusive. It served as a list of propositions for an academic disputation. He’d hoped it would lead to a debate among his fellow academics.

“What he didn’t know is that the person who actually sanctioned the sale of these spiritual favors was the very person to whom he sent a copy of his theses saying ‘isn’t this a terrible thing,’” Torvend said. That person was Albert of Brandenburg, the Archbishop of Mainz. “He was doing the sales of these personal favors in order to pay off the bribe he had given the Vatican for a promotion, and the bribe would then go to the building of the new St. Peter’s.”

Pope Leo X hoped that St. Peter’s Basilica, an elaborate work of Renaissance architecture, would eventually be his tomb. “It wasn’t about Jesus or the people, it was about his personal gravesite,” Torvend said.

Luther had just challenged the most powerful religious leader in Europe.

In the years leading up to the Reformation, heresy was often dealt with ruthlessly through agents of the Inquisition. But Luther’s challenge came at a unique time.

“The mass communication revolution of that time was the printing press,” Torvend said. The printing press allowed news of The Ninety-Five Theses to spread quickly and Luther’s words to be mass produced — words describing how many already felt, Torvend said.

Self Reflection

The Vatican quickly ordered Luther to recant his statements, but he refused. “His thinking was that the more people were coming after him, the more he was confident in what he was discovering,” Torvend explained. Through his careful study of the New Testament, Luther recognized that it is God who acts for human beings regardless of their spiritual status or good works. “It was about the liberation from anxious religion which Luther had been raised with his whole life.”

Luther also went on to translate the Bible into German. Up to that point, only clergy versed in Latin could read Scripture. But the Luther Bible was one that common people could read, and make up their own minds about. Studying the Bible and questioning its meaning was an important part of the Reformation. And for many Lutherans today, it remains so.

“It’s a complicated thing, you can open up the Bible and find one verse to prove just about anything you want it to,” said the Rev. Richard Jaech, bishop of the Southwestern Washington Synod who sits on PLU’s Board of Regents. “To seek the truth is not just a simple one-day task, it is a lifetime journey and adventure. The truth often is not one simple statement but many elements connected together and even in tension.”

Jaech explained that the two pillars of the Reformation are grace and vocation. He believes these ideals are as relevant today as they were in Luther’s time, and there’s a lot to learn from the Reformation.

“We live in a time of high anxiety,” he said. With news of economic turmoil, warfare and mass shootings, he said many people feel adrift. “I think a lot of people are yearning for some sense that their life means something.”

That’s why he thinks the idea of vocation — a strong value within PLU’s educational mission — is particularly important. “Each one of us has a purpose and a direction,” Jaech said. Part of life is figuring that out. But, Jaech said, “our life is not meaningless, our life is not purposeless, and that’s part of what the Reformation is about.”

Tyler Dobies ’16, who served as president of University Congregation during his time at PLU, was particularly drawn to the Lutheran notion of vocation. He was raised non-denominational Christian, but as he became more involved with worship at PLU, he became more interested in Luther’s teachings.

Dobies was particularly drawn to Luther’s ideas about vocation and purpose, as well as the idea of promoting diverse perspectives. Dobies said that means you don’t have to be Lutheran to embrace Luther’s teachings.

In particular, teachings about humility come into play. “Lutheranism does not presume that you are right,” Dobies said, “but that there is more to learn.”

Education

Torvend said questioning and self reflection are among the central ideals in Lutheran higher education. “First of all is the value of questioning what people assume is normal, but may not be healthy,” he said.

Inviting varied perspectives is central to that philosophy.

Torvend said Luther actually led the way in making education far more accessible in Europe. “In the reform of education, Luther was the first person in human history to ask that girls as well as boys receive an education, which had never been asked before.

“Privilege was always given to boys from wealthy families who could afford tutors,” Torvend said. “So, to ask that peasant boys and peasant girls be educated was a phenomenal, revolutionary act and request.”

Torvend also pointed out that during the Reformation, cities in Germany began supporting schools through taxes, a concept that at the time was unheard of. “What we take for granted as public education, which is supported through taxes, is a Luther invention,” he said.

But Torvend argues perhaps the most important Lutheran innovation in education was allowing every subject to exist independently. “That meant that professors in religion could not tell professors in geology or biology how to go about the study of their discipline; it meant that professors in psychology could not tell professors in English how to go about their discipline,” Torvend said. “There is to be freedom to follow the methods of every discipline in their own way.”

That means scholars, including those at PLU, are allowed to pursue ideas that challenge or upset both peers and superiors. It promotes the free exchange of ideas, free from censorship. It means no idea is above scrutiny — or beneath consideration.

That philosophy resonates with PLU’s continued mission of thoughtful inquiry, asking big questions and welcoming all perspectives to the table. As the university prepares for a year of Re•forming, an even bigger exploration of the core components of Lutheran higher education, it’s clear that Luther’s revolution isn’t over. It never is.