The Saint John’s Bible comes to PLU for a year, shares inclusive and universal message that will live for centuries

I wanted to carry it.

You know the feeling you get in a museum, surrounded by beautiful things — the overwhelming urge to touch what’s in front of you and experience history in a tactile way.

But this was different. I wanted to be close to The Saint John’s Bible. I wanted be a part of it.

I quickly learned that I already was, along with everybody else in the room at Saint John’s University on a hot Midwestern day in June. The Saint John’s Bible is for everyone, made by a diverse community to share with an even bigger one.

Rich community was the only way such a project was possible, says Suzanne Moore, a Vashon Island-based book artist who served as one of just two American illuminators for The Saint John’s Bible.

“It’s the only way it could get done,” she said in a sunlit art studio, reminiscing about her contribution to the most ambitious book-arts project of our time.

Moore was one of 23 artists who worked on 160 illuminations throughout the book, the first handwritten Bible since the invention of the printing press in the 15th century.

The 1,165-page manuscript, which has yet to be bound, and its authentic reproductions are massive — seven volumes, 2 feet tall and 3 feet wide when open. It takes 14 people to carry the whole thing into a church.

So, I couldn’t carry it. But I can tell its story. For me, the story mirrors Pacific Lutheran University’s mission — a deep commitment to liberal arts learning, care for others and social justice.

“The goal was to make it absolutely ecumenical,” Moore said. “They wanted an open-arms book.”

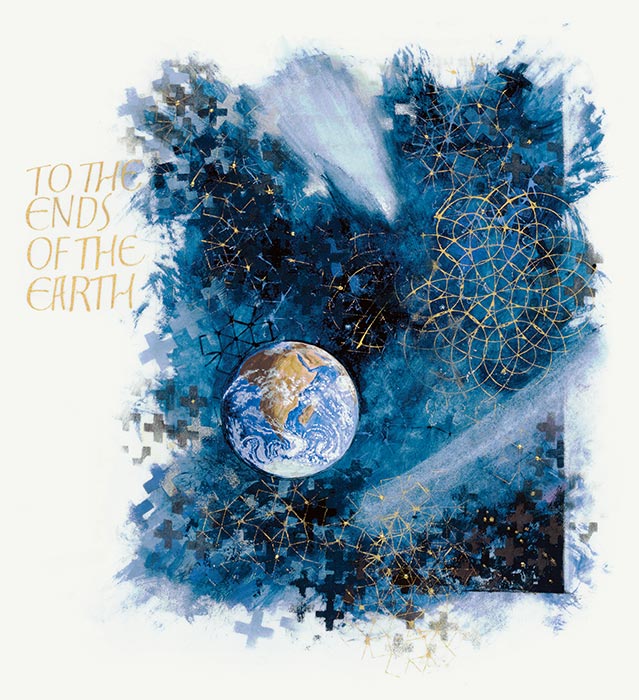

That’s exactly what The Saint John’s Bible is, in size and philosophy. PLU will use it to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation as part of its yearlong Re•forming series. The university is hosting a volume of the Heritage Edition — part of a series of 299 authentically reproduced versions designed to be shared more widely than the handwritten original.

The folks who commissioned this revolutionary Bible for the 21st century understand what I’ve always known PLU to understand: a commitment to a faith tradition that doesn’t leave anybody out, an understanding of the beauty behind faith and reason in one place — not in spite of each other, but in unison.

The Rev. Michael Patella, who led the Committee on Illumination and Text that guided the theological thinking of the project, said it best on that hot summer day in Minnesota: “Faith and reason are not at odds.”

A Look Inside

Gazing at the book feels like looking into history that hasn’t become history yet.

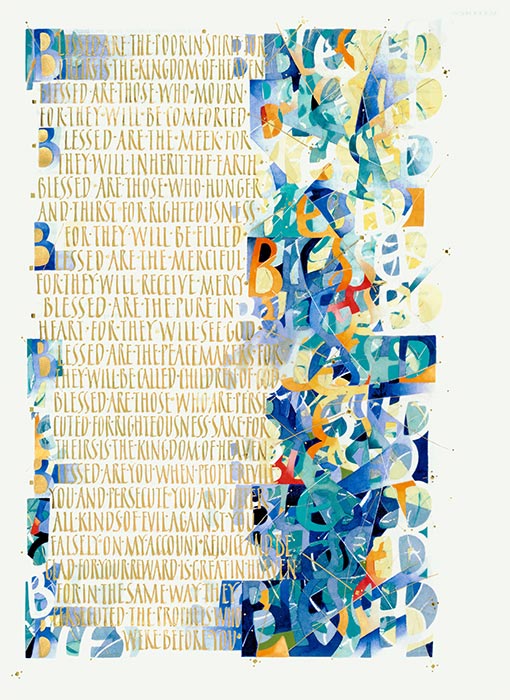

The art bursts with life. Butterflies and other insects, based on species native to Wales and Collegeville where the book was conceived, look as though they were plucked from nature and adhered to the pages. The detail is stunning. Inspecting the original pages with a magnifying glass in the Saint John’s University archive feels more like looking at colorful fossils in stone than paintings of bugs in a book.

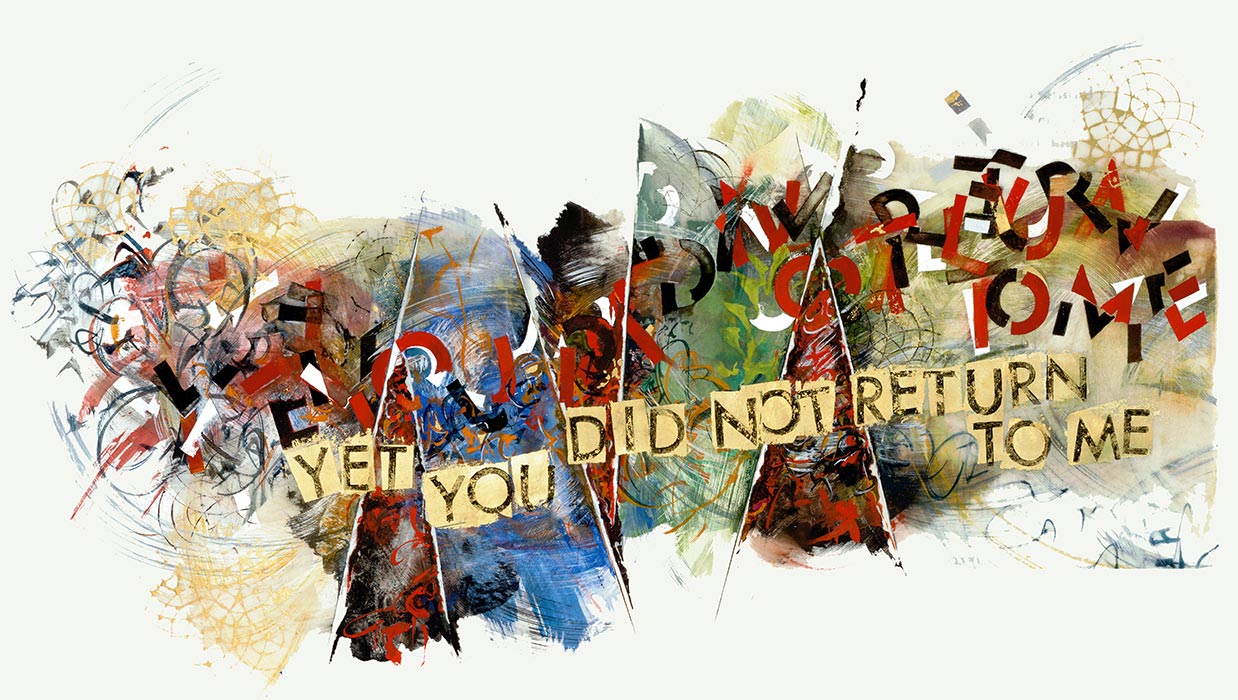

Light glistens on the gold leaf, dancing around the illuminations with every slight pivot. The sparkling accents throughout the book represent the presence of the divine.

Women and marginalized people can see their faces in the artwork. Science, anthropology, history, multiple faiths and more stand on equal ground, from the subtle use of DNA strands in the illuminations to the recurring use of Hebrew and Arabic text throughout the book.

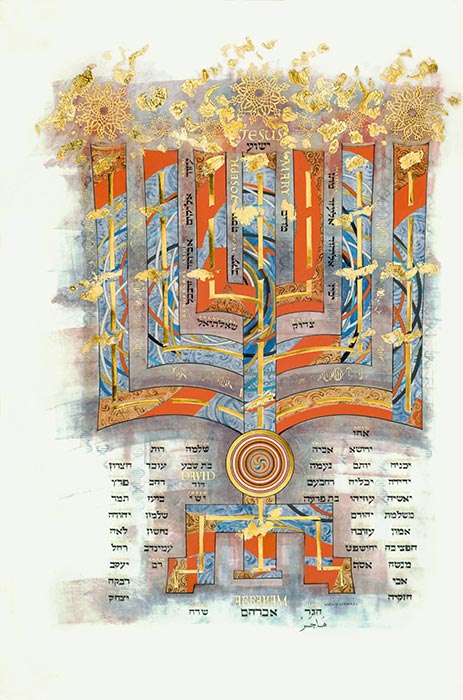

For the illumination “Genealogy of Jesus,” Moore said it was an “extraordinary stroke of genius” to depict a menorah as Jesus’ family tree. “Those spiritual traditions often have more in common than things that divide us,” she said.

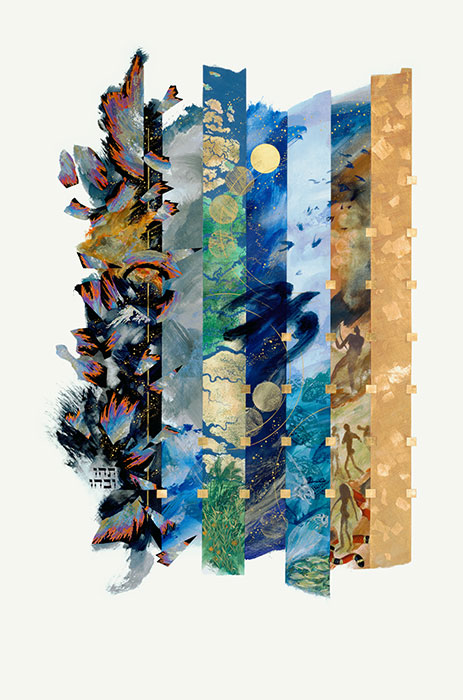

I always come back to the first illumination in The Saint John’s Bible when people ask why I was in Collegeville learning about a Bible; it summarizes the book’s narrative in a neat little package.

The story: Creation.

The task: creating an image of the story without making anyone mad.

No easy feat, but it seems the artists got it right.

The Saint John's Bible

Illuminations (select for full view)

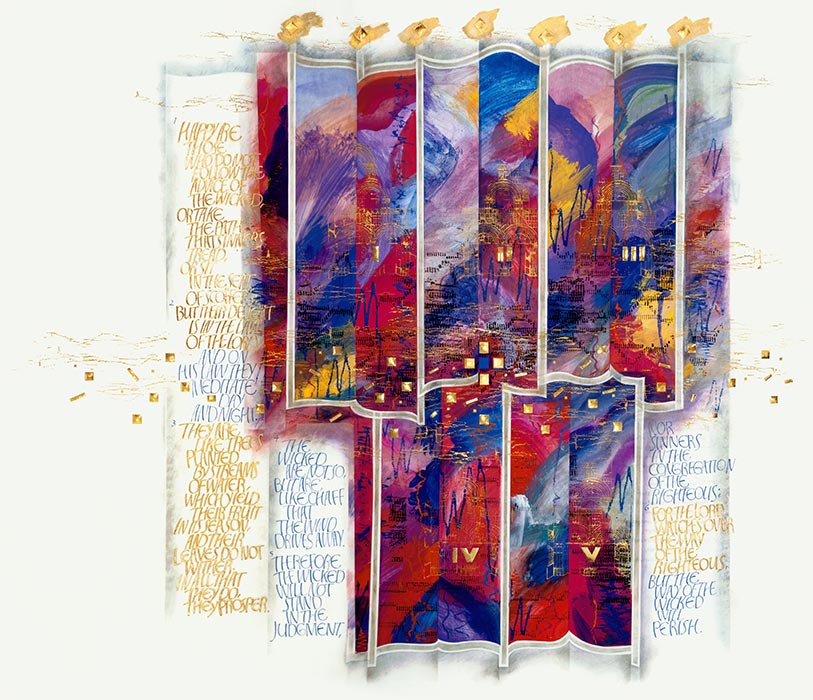

Seven panels denote the seven days it took for God’s creation. The image juxtaposes light and dark, chaos and order, all peppered with the familiar gold leaf, symbolizing the divine.

What is most striking, though, is the incorporation of multiple disciplines: satellite imagery of the Ganges Delta; prominent rock paintings that include one of the oldest depictions of a woman on the planet, a huntress from Nigeria; and fractals, geometric shapes that encompass never-ending patterns.

“That’s just the first page, folks!” exclaimed Tim Ternes, director of The Saint John’s Bible program. But he didn’t need to underscore the significance; the book already had my full attention.

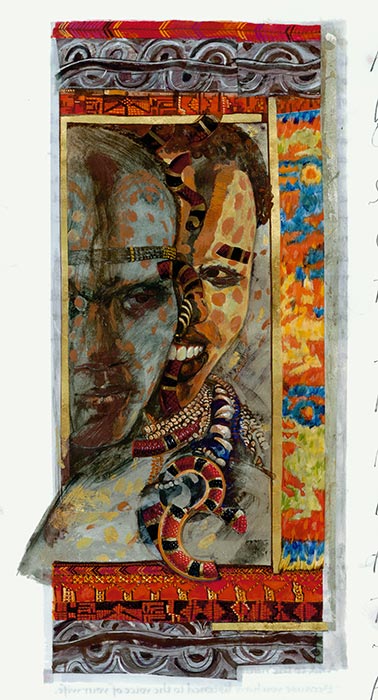

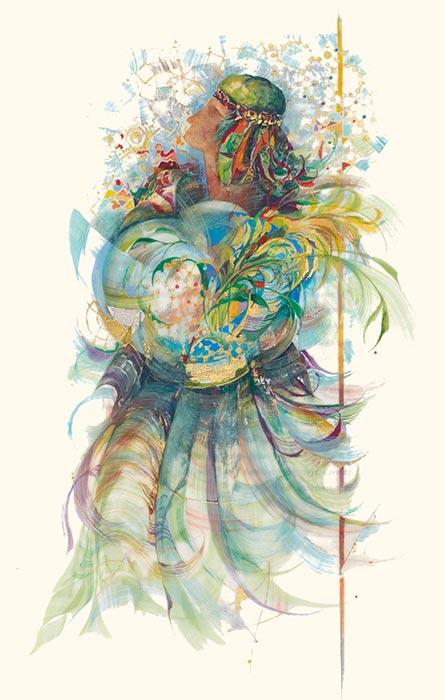

Then comes the illumination “Adam and Eve.” It is an image that helps me reconcile my long-held criticisms of Eve’s depiction in the Bible, a story I’ve always interpreted as placing the fall of humankind on a woman’s back. The pair in the illumination look androgynous (intentionally, I later learned) and have painted faces, inspired by photographs of the Karo tribe of the Omo River in Ethiopia — a beautiful nod to current anthropological theories that humankind evolved from our predecessors there.

For the first time, I saw an image of the beginning of humankind that made sense to me, an image that didn’t ignore what I’ve learned from textbooks. More importantly, it made me believe someone who looks different than me could see themselves in the story, too.

The Book of Psalms adds another layer of enchantment. A computer program recorded visual patterns of sound waves, drawn from audio recordings of psalms, chanting and sacred music from various religious traditions. Those visuals transform into a marriage of fluttering lines that dance on the pages, illuminated with gold trimmings and vibrant colors.

The sound waves of psalms run horizontal; those of the other traditions — Islamic, Jewish, Native American and more — run vertical. Together, they create an inclusive tapestry of sound that you see rather than hear.

The idea is to honor the physics of sound, which reverberates through the universe forever. For me, thinking about sacred music from all religious traditions coming together to represent the infinite nature of sound is a beautiful ode to universality. It’s unclear where the psalms end and the sacred music from other traditions begins. That’s poetic.

“These Guys Get It”

Donald Jackson, the official scribe for the queen of England, wanted to create a handwritten Bible since he was a boy.

In 1981, Jackson visited Saint John’s Abbey for the first time and knew right away that its partner university could be a contender to commission his lifelong dream. And eventually, it was. “Immediately he said to himself ‘these guys get it,’” Ternes said.

I understand the reaction. The church itself embodies artistic vision, with striking architecture that includes a breathtaking floor-to-ceiling wall of stained-glass cells that resemble a beehive.

The project was formally commissioned in 1998, thanks to an ambitious multimillion dollar fundraising effort. The first words were penned on Ash Wednesday in 2000.

The Committee on Illumination and Text communicated digitally with collaborators. Committee members included theologians, scholars, artists, historians and more. They researched passages and held visual brainstorming sessions, then sent their work to the international artists.

“They were never in the same room,” Ternes said.

The artists did their own research on the text, too, and after four to eight months of back-and-forth feedback, an illumination was born. “It was not an approval process,” Ternes said. “It was a discussion.”

Many calligraphers combined their talents to write in one streamlined style. The sweeping strokes covering the pages look uniform.

The inks they used (142 black ink sticks) were made in China in the 1870s from candle smoke and egg whites. The calligraphy quills soaked for 24 hours before being baked in hot sand. The vellum on which the words were written soaked in lime and water for weeks, before being sanded down to a soft, durable writing surface.

Let’s recap: a turkey feather transferred words made from candle-smoke ink onto calf skin, all so the pages could be digitally transmitted to dozens of collaborators worldwide. I’m still trying to wrap my brain around the juxtaposition of ancient and modern.

As the artists worked hard to create the intricate pages of the original Bible, Jackson and company worked simultaneously to design the volumes for each Heritage Edition.

A separate, equally meticulous process involved unprecedented printing techniques. The paper was carefully chosen to mimic the feel and weight of vellum. The transparency between pages was re-created with care, and the binding and embossing was done by hand.

Jackson penned the final word in 2011. After all was said and done, only nine corrections were made in the entire book. Not bad when accounting for the potential for human error with a project of that scope.

Even the Bible’s mistakes were beautiful, treated as artistic opportunities rather than errors, an homage to humanity’s imperfections.

A Year with the Bible

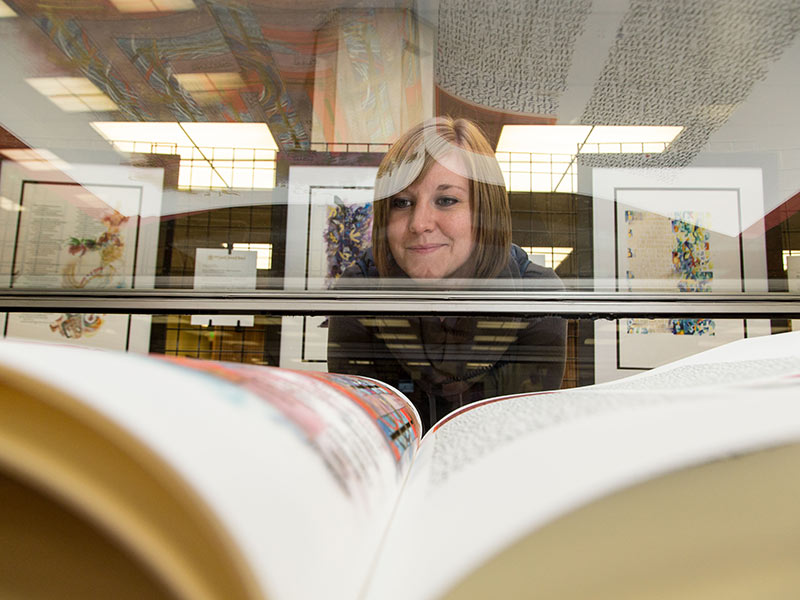

PLU welcomed the Gospels and Acts volume, as well as several framed illumination prints, Sept. 15 to begin its year with The Saint John’s Bible. The event included a presentation by Moore, the illuminator from Vashon Island.

Moore said the potential for an endless audience was the biggest draw for her participation in the project — an audience too broad to measure.

“We’re imagining an audience that’s unimaginable,” she said. “It can be very personal and hopefully universal.”

It’s clear that Moore and I aren’t alone in our deep connection to the The Saint John’s Bible.

When the volume arrived ahead of its debut at PLU’s library, where it will be displayed for a year, a group of eager professors and administrators gathered around the book. They thumbed through all of it (with squeaky clean hands, of course).

Every page sparked gasps, followed by awestruck silence. Each person leaned in closer, carefully examining every detail. They chuckled at the whimsically marked mistakes and marveled at the texture of the gold leaf.

Moore says many people have told her that the book keeps bringing them back. I understand the sentiment. I’ve yet to grow tired of looking at it.

“Can you ever see everything there is to see?” I asked Moore.

“We can’t predict that,” she said.

And that’s how The Saint John’s Bible will live forever, in spirit, well beyond its 2,000-year shelf life.

“We hope it will be something that will last,” Moore said.