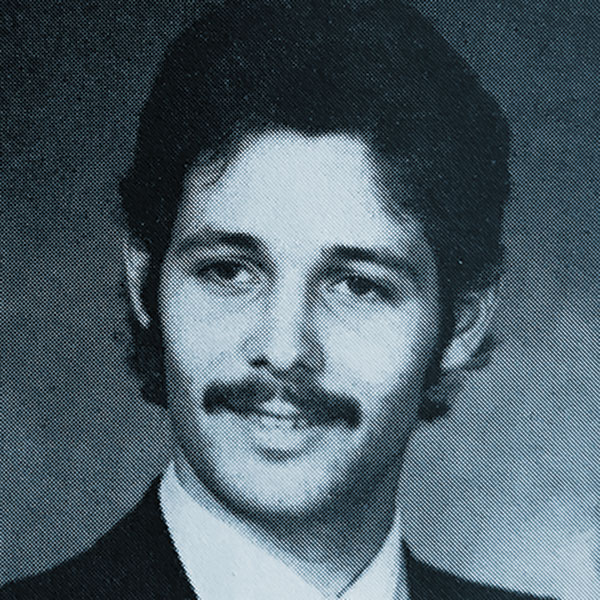

Attaway Lutes

PLU rowers reminisce about their daring journey in Puget Sound 50 years ago

Some of the rowers told their moms about the crazy idea. Others opted to beg for forgiveness, especially once the news hit the papers.

In hindsight, the Pacific Lutheran University crew team was happy Rich Holmes ’69 told his.

“She prepared a pot roast,” Holmes recalled of the pitstop at Saltwater State Park, more than halfway through a treacherous winter adventure in Puget Sound waters 50 years ago.

That December day in 1967, the fearless cadre of PLU crew members rowed an eight-oared shell from Seattle’s Lake Union to Tacoma. They started the “conquest of epic proportions,” as the local newspaper described it, around 5 a.m. and completed the 40-mile journey at Tacoma’s Point Defiance roughly 12 hours later.

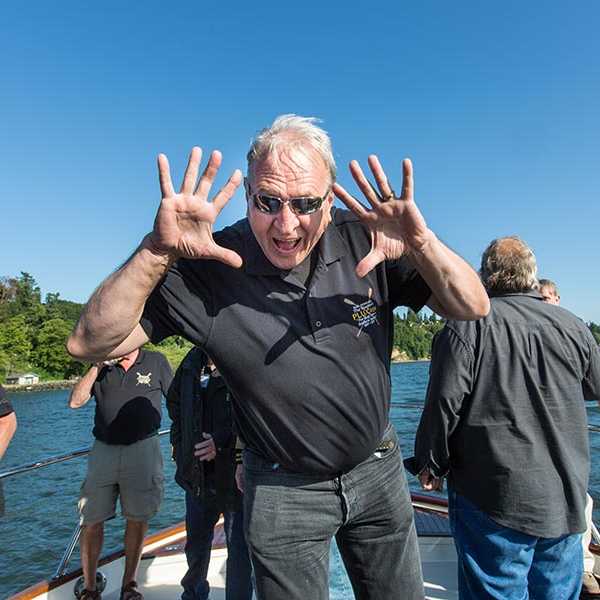

“I wouldn’t want to row out there now,” Holmes said, gesturing toward Alki Point on a warm summer day from the comfort of a private yacht where the former crew members gathered to commemorate the half-century anniversary and retrace their route. “I don’t remember the beautiful sights.”

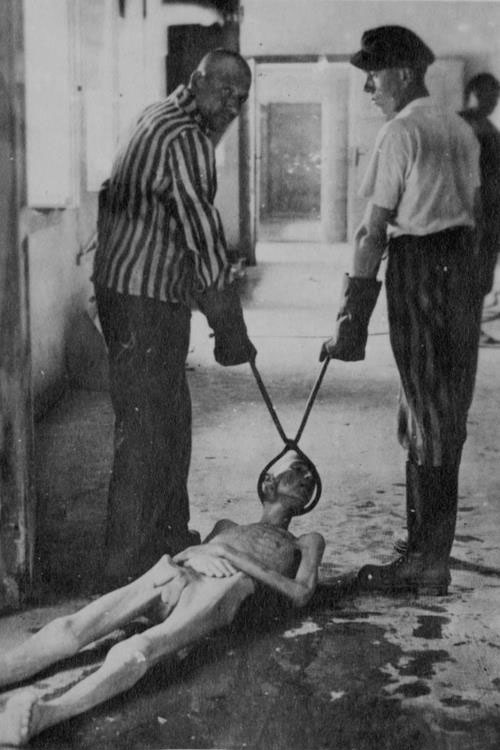

The lack of memories might have something to do with the ice-cold water that threatened hypothermia and the crushing waves that forced four rowers to trade oars for buckets as they furiously bailed water from the Loyal Shoudy.

“I didn’t think we would take on as much water as we did,” recalled Curt Pearson ’69, who was handed a bucket by the coxswain soon after entering Elliott Bay. “The boat was hardly moving. We had to do what we had to do.”

Making the trek wasn’t the smartest decision, and the rowdown participants are first to admit it. But crew was life in those days, and they needed a boat.

In the 1960s, the University of Washington lent shells to colleges to promote the Husky Clipper, the famous boat rowed by the 1936 Olympic gold-medalist UW team immortalized in the novel, The Boys in the Boat.

After PLU rowed the Clipper to victory in the boat’s final race against the University of Puget Sound and Seattle Pacific on American Lake, UW wanted its piece of history back. It was returned home to hang from the rafters of UW’s shellhouse at its Seattle campus.

In exchange, PLU was offered another UW boat, the Loyal Shoudy, with one stipulation: the Lutes had to transport it.

Slide for a before and after

At the time, men’s crew was coordinating all of their competitions and sleeping in churches and people’s homes on the road. They didn’t have extra money lying around to move a 60-foot shell.

So, like typical young adults who feel invincible, they said “let’s row.”

“When you’re 18 or 19 years old, you don’t realize potential consequences. We didn’t realize the hazard of it,” Jim Bartlett said. “I never let my parents know that I was participating in this.”

Bartlett, a junior-varsity coxswain called up for the rowdown, made it to Saltwater State Park where the group urged him to call it quits out of an abundance of caution.

“I dried off and was ready to go,” he said, acknowledging in hindsight that he likely was facing hypothermia. “They said I’d had enough.”

Eric Schneider ’70 said he respected his mother’s wishes and stayed home that day.

“My mom was adamant against it,” he said. “She had a premonition that I’d drown.”

Still, Schneider joined the reunion in June — an event organized by Jim Ojala ’69 that welcomed rowers who were in the Loyal Shoudy that day, as well as rowers who came before and after — and enjoyed reminiscing with his fellow oarsmen.

“I learned to row in the (Husky) Clipper,” he said. “We do everything together, this group.”

Schneider credits PLU with changing his life in many ways. Rowing was a big part of that meaningful change. “Crew gave me that stamina in life,” he said. “You just don’t quit.”

The camaraderie aboard the Rowdown Reunion boat this summer was palpable. “Last night, we got together and it was like no time had passed at all,” Norm Purvis ’70 said, looking around at the aged, yet familiar, faces.

The ceremonial cruise was the culmination of a full itinerary of events, including a tour of the Husky shellhouse and the historic one it replaced.

The yacht’s dark wood trimmings and plush cushions were a lot more comfortable than the conditions the rowdown crew faced 50 years prior along the same route. The men swapped war stories, political ideologies and reminisced about their rich lives — an encyclopedia of the good ol’ days.

The stories grew in scope as the wine and beer supply dwindled: “And they’re all true,” one of them quipped.

Rowdown Crew 50th Anniversary

Lauralee Hagen, senior advancement officer at PLU, said the hoopla experienced on board that day wasn’t unusual for the rowers. Former crew members maintain one of the strongest bonds she’s seen among alumni groups. “This is one of our most dedicated affinity groups,” she said.

Doug Nelson ’90, a former rower and PLU coach who serves as president of the Lute Crew Alumni Association, said the connection rowers have in the boat during competition carries into life.

“You have to be doing exactly what all your boatmates are doing at the exact same time,” he said of competitions. “Some of my best friends to this day are people I rowed with.”

Many of the rowdown crew members vividly remember the exhaustion that followed their incredible experience 50 years ago.

The next day, Holmes — with blisters on his hands and backside — managed to roll out of bed for chapel (direct orders from his girlfriend at the time). “I fell asleep,” he said, laughing.

Pearson has pored over stories and photos with his grandchildren many times over. Despite the clear dangers they thwarted and the criticism they faced ahead of time, he makes no apologies.

“Call us young, foolish, stubborn, irresponsible,” he said, “but when you get out there and you do it, you won’t let your teammates down.”