“She offered personal support and also has helped my writing style,” Sophia Mahr ’18 said of Beth Kraig, professor of history, who worked very closely with Mahr on her research of unethical medical studies. “Beth is one of the most accessible professors I’ve ever had.”

Sophia Mahr '18 knew the devastating numbers. She knew stories of survival and stories of deep suffering. But seeing the concentration camps, and the faces who carry on a survivor’s story, offered Mahr new eyes through which to examine the tragedy experienced during the Holocaust.

“Being with the Mayer family gave me the personal connection,” she recalled of her January 2015 study away experience. “That really moved me.”

Mahr, then a wide-eyed first-year student, participated in a study away course in Germany alongside the family of Kurt Mayer, the late Holocaust survivor and educator whose name informs one of Pacific Lutheran University’s most distinguished programs, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Though she didn’t know it at the time, that emotional glimpse into the past helped inspire later research and her overarching vocational path.

“It made me realize that I could combine global studies and Holocaust and genocide studies and really have an impact,” said Mahr, who is majoring in the former and minoring in the latter. “I really got into that mindset for the rest of my time at PLU.”

That mindset resulted in a research project that helped her grow as a student, an academic and a human being. Her conclusions urge society to confront uncomfortable truths about 20th-century medical studies conducted at the expense of marginalized populations, and the subsequent findings of those studies that are, in some cases, used and cited in contemporary research.

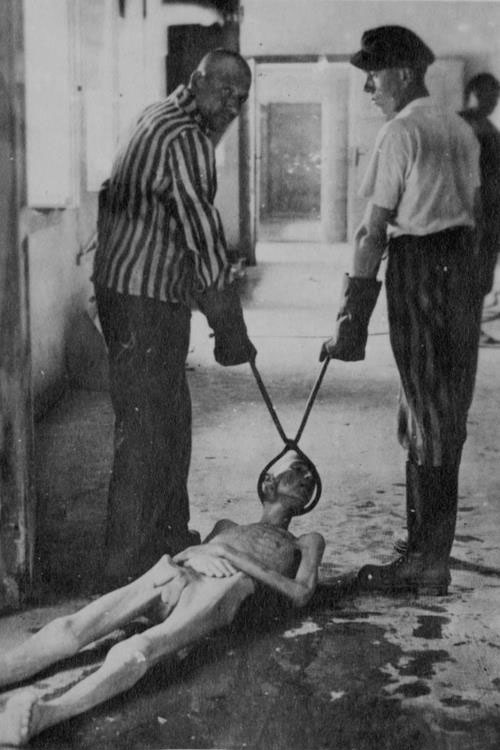

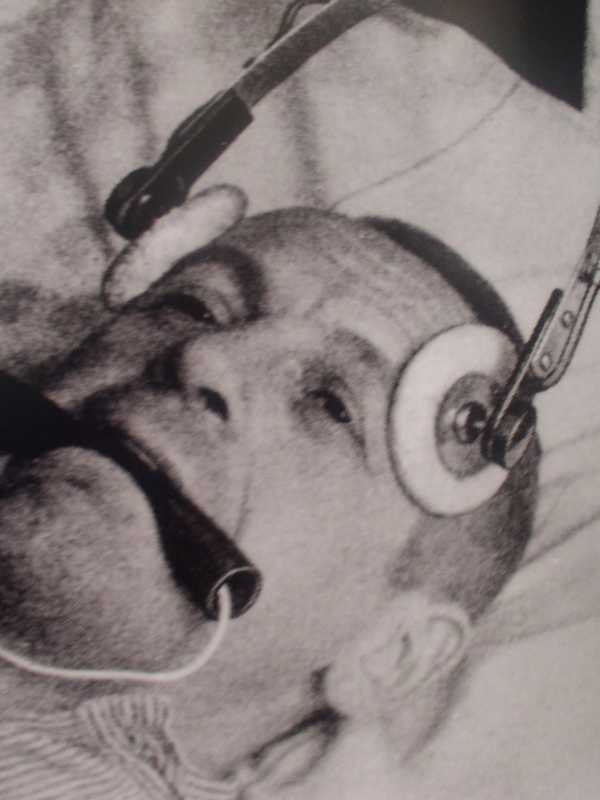

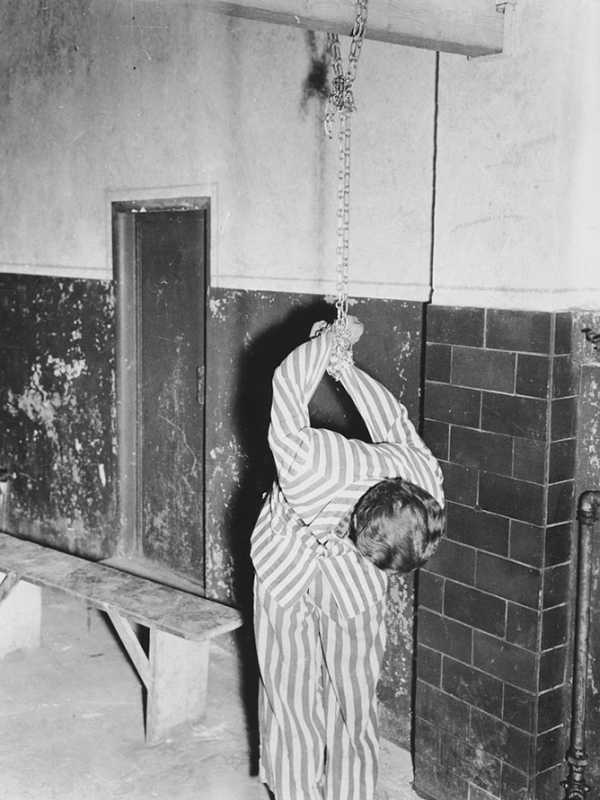

Mahr analyzed how and why medical providers repeatedly and deliberately harmed people in the name of medical science by conducting non-consensual experiments on their subjects. Those ambitious professionals, she says, argued that the ends justified the means — that the harms were necessary to foster a greater good.

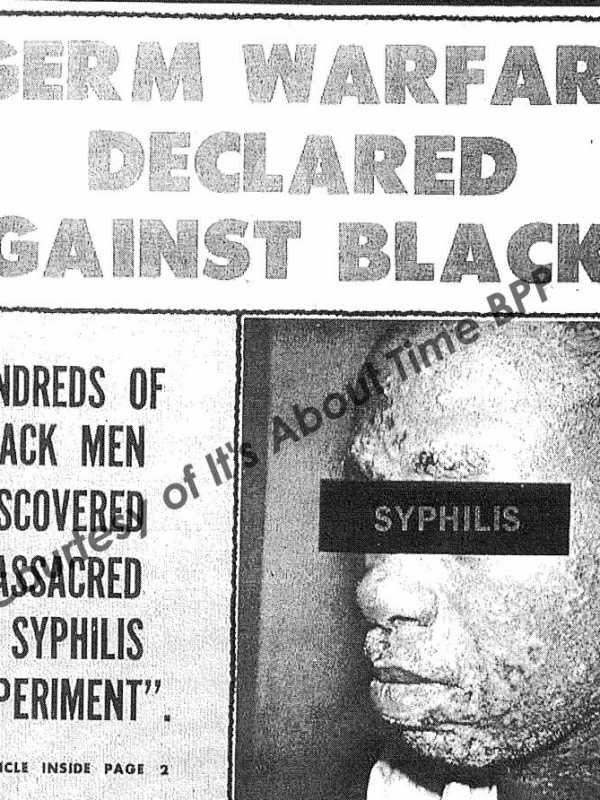

Within her research, Mahr examined three case studies of unethical human experiments: torture of Jews in Nazi concentration camps, the Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis in rural black men, and the coerced research and medical discrimination of LGBTQ individuals.

Mahr argues that the systems in place, which have evolved over time to protect patients, continue to be violated in a dangerous trend.

“This is not an isolated reality,” she said during a campus presentation of her findings at the inaugural Undergraduate Research Symposium in April. “We use a lot of this research today.”

Mahr said one key factor, among many she discusses in the paper summarizing her work, is the lack of enforcement mechanisms. From the Hippocratic Oath taken by medical professionals to the Nuremberg Code that underscores full and informed consent in medical studies, Mahr says all rely on the honor system and the goodwill of authority figures. Failures and loopholes in protections are evident, she stressed, and actively aware citizens are the key to preventing future violations.

“Trusting blindly that this system will prevent medical abuse keeps us from looking actively at the harm that’s done,” Mahr said in her presentation. “My research led me to believe that we need to be more actively aware. We always need to be on the lookout for violations of consent. It’s about testing these systems of power.”

Beth Kraig, professor of history, mentored Mahr through the emotionally taxing process of tackling this appalling reality.

Kraig said Mahr’s work challenges society to put more pressure on institutional systems to implement checks and balances. It also challenges people to face the possibility that they could become complicit in harmful behavior.

“She’s wanting people to take this on board as something they are prone to do themselves,” she said.

In all the case studies Mahr examined, Kraig said, the people aiding in the corrupt treatment believed they were doing the right thing. “If it’s doing real harm it might come in a package that says ‘I’m doing real good,’” Kraig said.

For example, one of the most cited medical studies Mahr examined was the Dachau Hypothermia Experiments, which took place at the first Nazi concentration camp opened in Germany. The victims were submerged in vats of icy water, naked and outdoors in freezing temperatures, only to be rapidly reheated with scalding water, among other horrifying trials. Many prisoners were killed in the attempt to learn how best to prevent and treat hypothermia in German soldiers.

Kraig said the torture resulted in the discovery that it’s better to warm hypothermia patients as fast as possible, rather than heating them up gradually as medical professionals previously thought.

“That became, and still is, the best method for preventing death,” Kraig said. She added that Mahr’s research forces people to confront the uncomfortable truth that better treatment for hypothermia patients today is the result of great harm, and even death, to many who came before them. “That’s the complexity Sophia wants people to engage.”

Kraig said she offered much needed emotional support for Mahr, someone she describes as kind and empathetic. “We had lots of difficult, deep conversations,” Kraig said. “It was tough for her to come to grips with how untrustworthy many institutions are.”

The struggle Mahr had is one many students should come to terms with, Kraig said — learning to live with discomfort.

“Expertise, emotions and ethics all have to be considered in this work,” she said. “You can’t just honor the expertise. You have to develop habits of skepticism.”

Kraig said the extensive research process taught Mahr to be independent in her quest for sustained inquiry: visiting archives on her own, reading sources she discovered on her own and doing so outside the classroom without the motivation of a grade.

“It opens the door to how much more there is to know,” Kraig said. “It’s a point of pride and a little bit daunting.”

Kurt Mayer Student Research Fellowship

Sophia Mahr’s research on unethical human medical experimentation was made possible by the Kurt Mayer Student Research Fellowship, offered through the Holocaust Studies Program at Pacific Lutheran University. Mahr received the fellowship in summer 2016. Recipients produce original research and present their findings at the annual Powell-Heller Conference for Holocaust Education.

“I was so honored to be a Mayer scholar,” Mahr said, adding that her research is deeply rooted in Kurt Mayer’s legacy.

While Kraig helped Mahr academically and emotionally, the professor admits she learned from the process, too. The pair shared reading materials with one another, resulting in new discoveries traveling both ways.

“We had a very common foundation of knowledge to share. It’s 100 percent co-learning,” Kraig said. “These projects start with the student.”

Now, with about a year left at the university, Mahr feels better prepared for her next steps. She recently completed a Minneapolis-based internship with a refugee resettlement and immigration program and is figuring out how she can continue to aid refugees amid ever-growing crises around the world.

“I know in my heart that I want to help with refugee migration,” she said. “This research is not my finale, it’s a building block.”

In the meantime, she will continue to urge her peers to think critically about the topic she’s grown so passionate about, no matter how uncomfortable.

“This is not just something to think about for history,” she said. “This is something to think about for the future.”