Alternative Routes to Certification

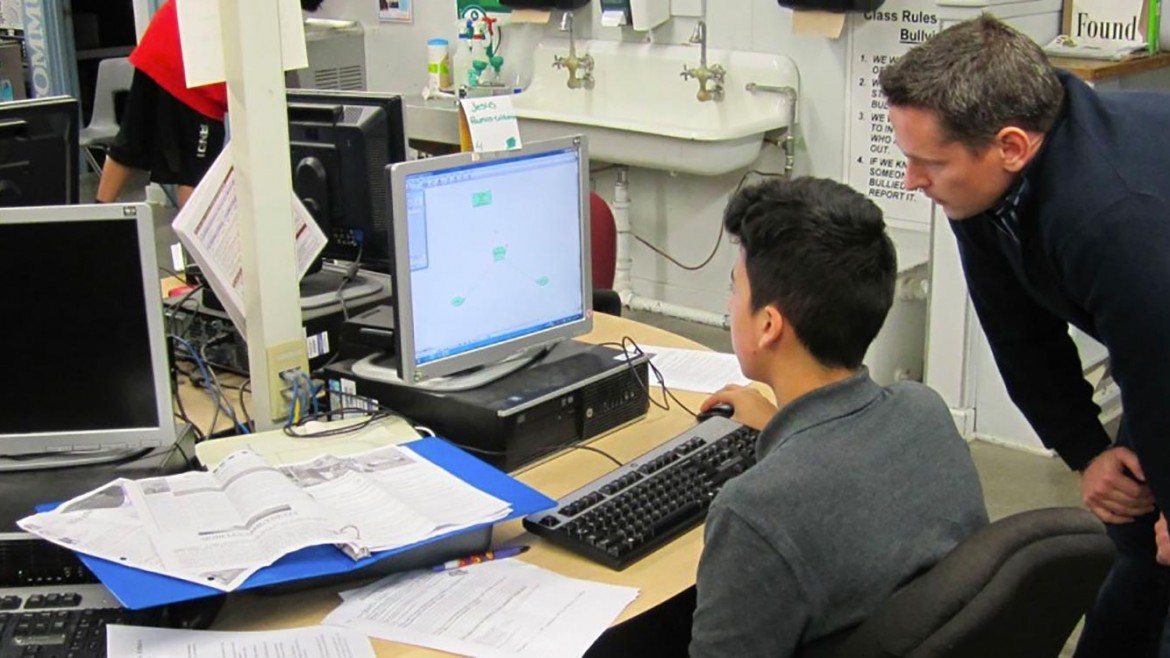

Garrett Wade bounced from desk to desk in a crowded classroom, guiding his students through the online program they were learning at Sylvester Middle School in Burien.

“Mr. Wade! Mr. Wade! I need your help,” a few chimed in from different corners of the room.

Wade, alongside longtime teacher Darrell Chase, calmly commanded the classroom as though he had done it for years. Yet, the 38-year-old is in his second year of teaching, and he credits his immediate success to the intense preparation at Pacific Lutheran University through the Alternative Routes to Certification (ARC) program.

The intensive, primarily field-based program within the School of Education and Kinesiology offers individuals a high-quality, accelerated route to certification in high-needs educational areas, specifically special education.

Through the yearlong program, candidates gain hands-on classroom experience while simultaneously taking flexible classes that work around professional and family life.

“PLU does a fantastic job fast-tracking good, qualified teachers,” Wade said, adding that school districts don’t hesitate to bring a PLU graduate on board. “The brand speaks for itself. They are only endorsing and signing off on well qualified folks.”

PLU has already trained many new teachers through ARC. And a state grant has been helping the university train even more.

In 2016, the education department earned a block grant that totaled nearly $590,000 in funding spread over two years.

It was the first year the state required universities to apply for grant funding to pay for ARC, said Lauren Hibbs, director for partnerships and professional development in the education department. Only nine programs statewide earned funding, and PLU tied for the third-highest award amount. Hibbs said earning the grant money speaks to the legitimacy of PLU’s program.

“It’s demonstrating that the state is supporting our model of preparing teachers,” she said.

The money funded scholarships for 21 students enrolled in the ARC program each of the following two years. It also covered administrative costs and activities tied to student development, such as mentoring and workshops. The individual scholarship amounts are valued at $8,000, covering nearly half the cost of tuition.

The program also has partnered with regional school districts, including Franklin Pierce, Bethel, Puyallup and Clover Park, as well as the Puget Sound Educational Service District, which works to improve the quality, equity and efficiency of of programs in K-12 education.

Districts involved in the partnership often identify non-certified candidates already working in the schools to enroll in PLU’s program, said Vanessa Tucker, assistant professor of education. She said schools recommend people with the expectation that they will be hired into full-time positions once the certification process is complete.

“The program supplies the teaching force with non-traditional students,” Tucker said, “people who would be wonderful additions to our field.”

Wade is certified to teach special education and earned a language arts endorsement through the program. He teaches five class periods a day at Sylvester Middle School, where he was paired with a mentor and completed his internship during his time in ARC. Wade said he secured the full-time job before he even finished the program, something many of the peers in his cohort were able to do, as well.

“It allowed me to hit the ground running,” he said of ARC. “I was able to jump right in and make it happen.”

Wade said teaching at Sylvester has its challenges. About 73 percent of the students qualify for free or reduced lunch at the high-poverty school. But ARC prepared the husband and father of three with a rigorous education, Wade said, all without disrupting his life outside PLU. The former small business owner said he always, in the back of his mind, considered becoming a teacher. PLU made that distant thought a reality.

“PLU does a fantastic job fast-tracking good, qualified teachers. The brand speaks for itself. They are only endorsing and signing off on well qualified folks.”

– Garrett Wade

“I really felt that was the best fit,” he said.

Hibbs said ARC gives access to individuals who otherwise might not have the chance to earn a certification: “This is providing a way to increase diversity and provide a pipeline of people who aren’t on the traditional route.”

According to a survey conducted by the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction in 2015, 45 percent of principals say they weren’t able to fill all of their teaching jobs with fully certified candidates. More than 80 percent were required to employ teachers with emergency certificates or as long-term substitutes, and 93 percent indicated that they were “struggling” or in a “crisis” mode for finding qualified candidates.

Tucker underscored the need for teachers, especially those in high-needs areas. She said the district partnerships tout a “grow your own” philosophy that creates a direct route for candidates with a proven track record of success in the classroom.

“This really places the partnership at the forefront,” Tucker said. “Districts are desperate for people.”

And the people PLU certifies are not only quality candidates, but diverse, fun professionals with a lot to offer: “The diversity and background of these people is huge,” Tucker said. “They bring tremendous life experience with them.”