Open Books is a hub for the poetry community, locally and nationwide. But to Billie Swift ’16, it’s so much more.

It’s where she would end her regular scenic drive from South Seattle, a route along the lake that helped her young children gently doze off so she could quickly snag a book and indulge in new poems.

It’s where her husband and children have gone each year before Christmas to find Mom the perfect gift.

And it’s the only place where she has long sated her deep love for poems and bookstores, simultaneously.

So, when she learned that the owners were set to sell the poetry-only shop they started two decades earlier, Swift’s reaction was nearly reflexive.

“Has it happened yet?” her husband immediately asked upon hearing the news, knowing his wife’s next move was likely a question of “when” not “if.”

“Everybody kind of knew,” Swift recalled of her decision to buy the store.

The serendipitous timing was practically poetic.

Swift purchased Seattle-based Open Books: A Poem Emporium just as she finished the Master of Fine Arts program at Pacific Lutheran University. The Rainier Writing Workshop — a three-year, low-residency program — provided Swift an outlet to pursue a graduate degree in creative writing.

Open Books provided an outlet to continue to foster the community she built within the program.

“The driving force was just that I wanted a poetry bookstore to exist,” Swift said. “But knowing I would be able to stay connected to the poetry community was good to know.”

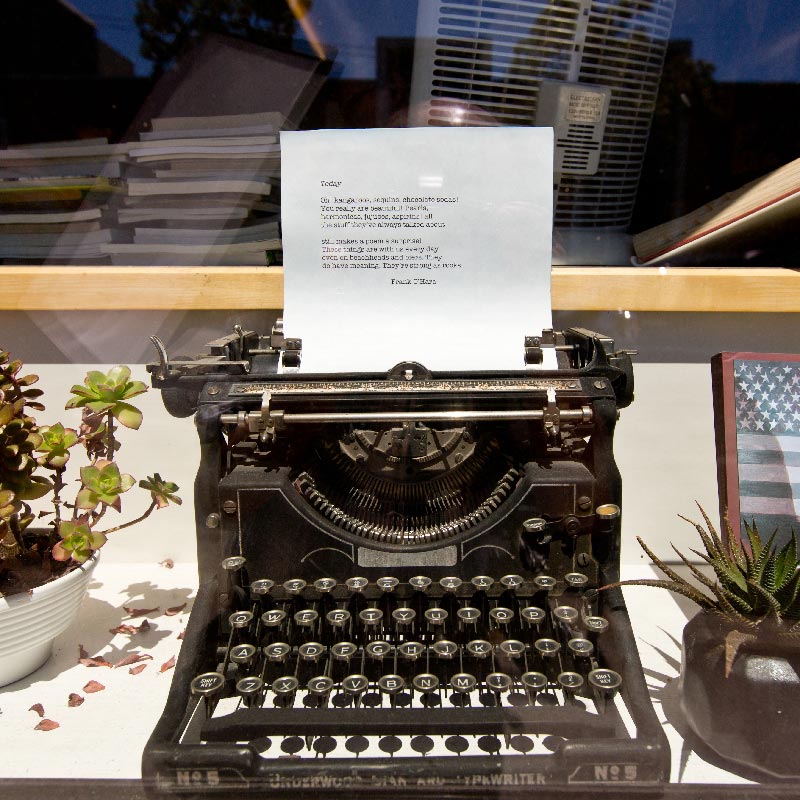

The store is one of only a handful of its kind in the country. It carries more than 10,000 titles and provides a place for enthusiasts and poets alike to quietly peruse, read or talk to like-minded customers. It also hosts regular events, such as readings.

“Hopefully, any name someone knows as a poet we carry in the store,” Swift said.

Rick Barot, director of PLU’s MFA program, is a longtime customer. He already knew about Open Books before moving to the Tacoma area in 2005, when he joined PLU as an assistant professor of English. He took over the MFA in 2014, a program now entering its 15th year.

“One of the first things I did when I arrived here was make a pilgrimage,” said Barot, now an associate professor. “I made it a policy, personally, that all the poetry-related books that I buy I only buy from them. I know other poets who have that policy.”

Swift took that policy to the next level when she took over the bookstore from John Marshall and Christine Deavel, the original owners who ran the shop since 1995.

“This space feels like walking into a poem,” Swift said. Preserving it, she added, meant preserving “a space devoted to poetry, and what it means to be enveloped by something that I love and I know a lot of people love, to walk into a space that’s saying it matters enough that it’s all we’re doing.”

Swift, a former newspaper and magazine editor, says poetry came into her life after her undergraduate years studying English at Barnard College in New York City.

“It wasn’t until after college that I fell head over heels for poetry,” she said. “I was learning by going to The Strand (bookstore in New York City) and reading anything I could find.”

After moving back to Seattle, where she grew up, the lifelong learner and avid reader started taking poetry classes at Hugo House, a nonprofit “place for writers.” That cemented her future plans as a poet.

“When the urge to go back to school got big enough, I had to figure out what to do with that urge,” Swift said.

Raising children complicated matters; she wanted to be present. So she started to look into low-residency programs, ones that offered both rigor and flexibility. She also craved intense mentorship.

Rainier Writing Workshop was the perfect fit, so perfect she wondered if it was too good to be true.

“I realized it was exactly what I was looking for,” Swift said. “The emphasis of the program was on figuring out what being a writer means to the individual, and not necessarily trying to figure out how to be a successful writer. I was definitely more interested in the former.”

Barot says that’s by design.

“We have a structure, but we don’t have a curriculum,” he said of the program. “All of these people are coming here with very different backgrounds and levels of knowledge beforehand. Each mentor has to tailor their mentorship to what each writer is doing.”

The MFA — with concentrations in the genres of fiction, nonfiction and poetry — spans three years with an immersive 10-day residency at the start of each year, complete with morning-to-night readings, workshops and lectures.

“You leave loaded with this desire and urgency and bewilderment. All at once. Because you’ve now just been inundated with really great poetry, with really great thoughts on poetry, with a cohort that is writing really great poetry, and now you get to go home and figure out where you fit in all of that.”

The most recent residency, for example, included a panel of five faculty members addressing one question: “Why did the writer cross the genre?”

The writers discussed their experiences working across genres: the internal tension, the infusion of creativity, the challenges, the unexpected triumphs. Dozens of MFA students, hooked on every word, scribbled notes and intently listened. One attendee was overcome with emotion as she asked a question at the end, apparently grappling with insecurities within her own process.

Swift says that’s not uncommon.

“Everybody cries at some point,” she said. “You leave loaded with this desire and urgency and bewilderment. All at once. Because you’ve now just been inundated with really great poetry, with really great thoughts on poetry, with a cohort that is writing really great poetry, and now you get to go home and figure out where you fit in all of that.”

The remainder of the MFA work happens between the students and “intentionally attentive” faculty mentors, as Barot describes them. Each month, students work on assigned readings and write critical papers for review by their mentors. The work isn’t always limited to one genre, Barot said: “What’s interesting about us is we celebrate multi-genre work. Writers might study other genres or be asked to study other genres to explore their creativity.”

And the faculty mentors are key to emboldening that exploration: “These moves across genres can actually fuel more interesting work,” Rebecca McClanahan told the captivated group during the residency panel.

The mentors meet or talk regularly with their assigned writers, and the monthly work evolves to cater to each individual writer.

“Different people have different ambitions and goals,” Barot said, stressing that some students want to be published, while others simply want to be better writers. The program honors those diverse goals, he added. “It’s kind of an ethos that we really value and practice in the program. It’s rigorous, but supportive.”

Swift says that ethos extends beyond the Rainier Writing Workshop to the larger poetry community, and lives in the bookstore she’s owned for just over two years.

“We are hungry to read each other and support each other,” she said of poets.

And Swift says encountering poetry — whether it’s dissecting its meaning or just feeling something — is so important to experience in community.

“It’s a solitary act, the act of writing. But you do it because it’s also a gesture outward,” she said. “Having space for that outward moment, to allow that to happen, there are some spaces, but there aren’t a lot.”

That’s at the heart of Open Books, as well as the Rainier Writing Workshop at PLU.

Barot believes the MFA program planted the seed that grew into Swift’s desire to acquire Open Books, and continues to empower writers to come out of solitude.

EVENTS AT OPEN BOOKS

Rick Barot will teach a two-part class Oct. 21 and 28, 2018, 10 a.m.- noon (registration required). Open Books also will host a launch party for the latest issue of The New England Review, where Barot is the poetry editor, on Oct. 20 at 7 p.m. Visit the Open Poetry website to learn more about these and other events at the Seattle bookstore.

“Being part of the program is like being part of a nerdy club. It’s hard to get that on your own,” Barot said. “That’s the kind of ripple effect a program like this can have. They spread it to the communities they are a part of. The programmatic DNA is passed on.”

And, of course, a master’s degree that comes with it. Barot says that’s an “add-on” for many, though it opens up opportunities for professional advancement, teaching jobs and more.

The program culminates in student manuscripts — ranging from compilations of poems to collections of short stories to novels — and many of the students’ works are eventually published. But beyond that, they leave with the network and the confidence to pursue writing their way.

“Your tool kit should feel really heavy, in a good way,” Barot said.

Swift’s tool kit is overflowing, and she’s using it to share poetry with everyone. Because poetry is for everyone, she says. “Poetry is the act of expressing, thinking, feeling all at once,” she said. “I like to remind people that poetry is there for them.”

And, Barot says, Open Books is there for the genre, thanks to Swift. “It’s a symbol for how important poetry is,” he said.

Swift is back to focusing on her own work, something she drifted from amid the whirlwind of the bookstore purchase. “I write small poems, and I take a while to do it,” she said. “My body of work is not huge.”

Her chapbook, based on her MFA creative thesis, is scheduled to publish in May of next year.

In the meantime, she’ll continue to invite poets — from the Rainier Writing Workshop and elsewhere — to sit in the thick of it with her at Open Books, celebrating poetry in all its forms.

“There’s this heartbeat we’re all circling, and we can’t name it,” she said. “But we’re all trying to.”