Cover Story

EL LIMONAL, Nicaragua—The phrase “adapt or die” comes to mind.

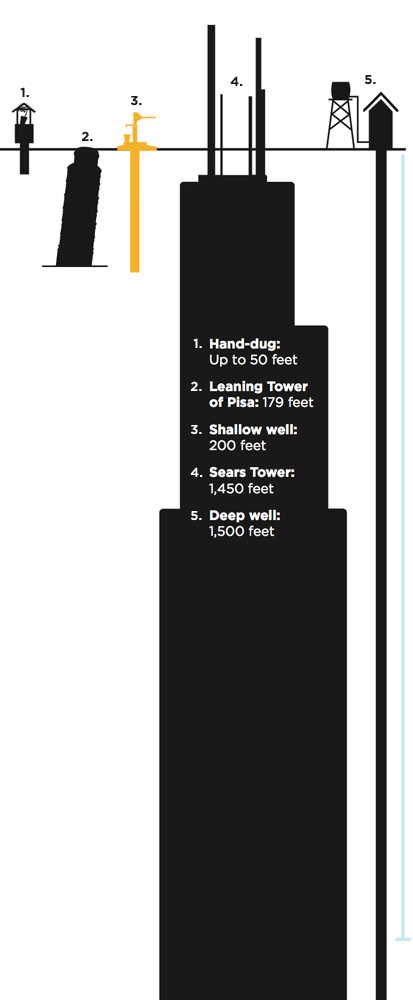

In an effort to cut down the heat, someone scavenged a parachute that gives a big-top feel to the construction site where a team from Pacific Lutheran University is installing a life-changing well. Unfortunately, the parachute also cuts the breeze and traps the heat from the pumps. Still, shade is shade, so four of the students doggedly work through the afternoon as the drill grumbles and chews its way through 150 feet of mud, rock and clay to an aquifer beneath the village, which is about three hours from Managua and on the edge of a smoldering garbage dump.

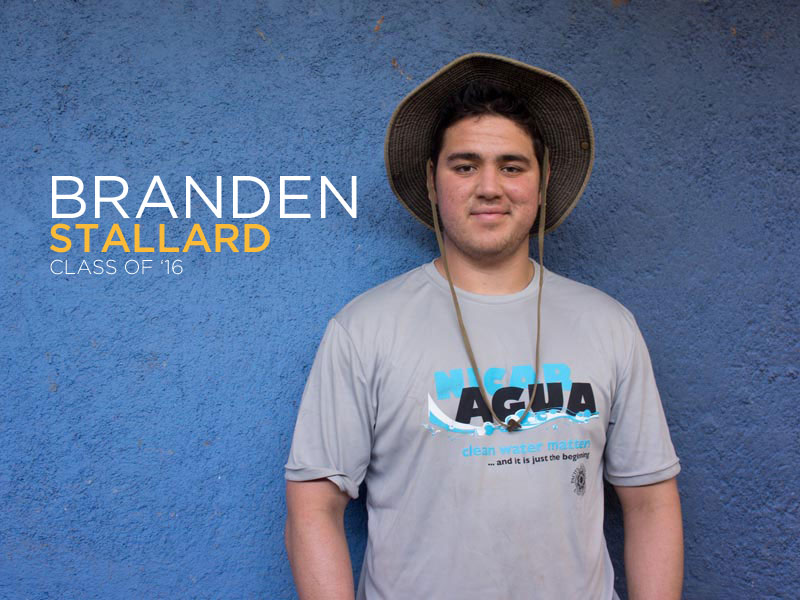

Branden Stallard ’16 and Rachel Espasandin ’14 get soaked in a muddy slurry that whirls out from the drill every time it comes up for a new length of pipe. Both quickly become hash-marked from head to boot with mud. Shirts and pants sag into a soggy chocolate skin. Hands stain with mud and a red grease that smells vaguely of cherry nail polish.

Even the Living Water International staffers partnered with PLU admit the heat is crushing; they’re amazed at the fortitude of these Northwest students who certainly could have found something more fun to do for five days over spring break.

“This heat was terrible for me,” says Living Water’s Douglas Varela, drill manager for the dig. “I don’t see how they can do this, but they do.”

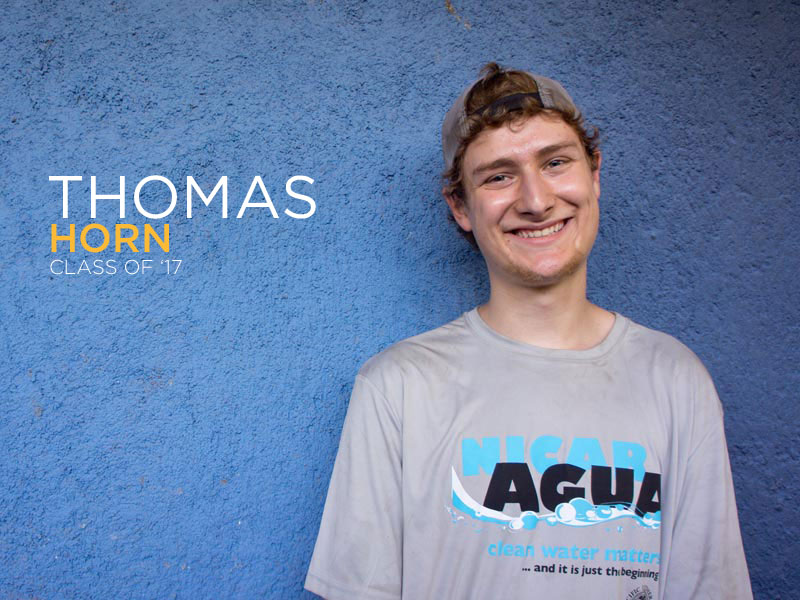

While Stallard and Espasandin work on the drill, one feeding it metal tubing that’s pulled into the ground by the drill bit, and the other carefully guiding the drill through the soil, Thomas Horn ’17 is working up a bentonite sludge that will stabilize the well walls as the drill corkscrews deeper into the earth. While he’s covered in slate-colored goo, another important event occurs, though Horn is too busy to notice: Subtly and with no fanfare, village men, who have watched politely from the sidelines as the PLU teams worked the drill and led the women and children in hygiene sessions, have decided that Horn is one of them.

It happens as the lanky blond Horn tries to wrestle the 60-gallon water drums that the villagers stockpiled for this project over the last two weeks.

The water is poured into the trench, which curls into a well hole. If it’s possible, it’s even messier work that the drill crew faces. Horn is quickly coated with a slate-grey crust. The four village men begin to splash water on his arms to take off the paste, or scoop water onto him to catch his attention or cool him off. While the children of the village immediately took to the PLU students—especially if they play soccer with them, give them piggyback rides or offer their phones or cameras for selfies—this was one of the first times an adult reached across the barrier of language and culture to make contact.

Later, at the Living Water compound about 45 minutes south of El Limonal, Horn, who walked into the shower fully clothed to shake the caked mud, reflects on the day.

He considers it a privilege to work with this group and is humbled by its acceptance of him. Before leaving for Nicaragua, he admitted he was a bit worried about how the villagers would react to a bunch of American students showing up. But the reception has been so welcoming, he is simply speechless for a moment. Then he turns to the issue of water.

“I want everyone else to have the same privilege I have,” he says: When you turn on the faucet, you get clean water, immediately.

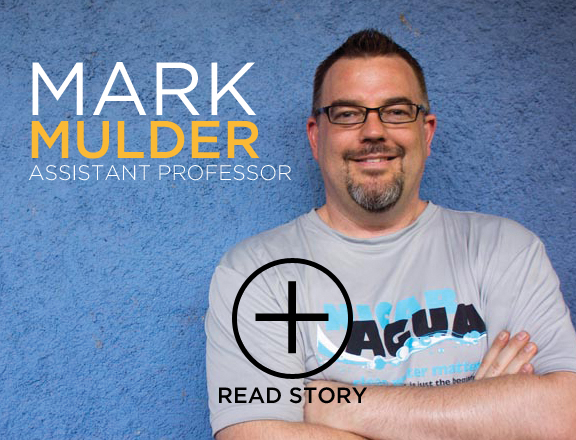

And that’s the basic purpose of this trip: Ten PLU students—in conjunction with Assistant Marketing Professor Mark Mulder—set out to bring clean water to a community that did not have a reliable source of this precious commodity. But the trip also was about building relationships, some immediately and some cautiously, but all connections that ended up changing these Lutes forever.

Meet the Team

Click on the photos to hear each Lute’s story.

Day One:

El Limonal,

Nicaragua

Church Courtyard

Depth:90Feet

“I always knew this project was going to happen,” says one of the key organizers of the trip, Alex Quiner ’14, after his first day of digging, and only slightly less plastered with mud than Horn. “I just didn’t know if the trip would happen before I left the university.”

But it did, and on the beginning of Spring Break, the students piled onto an Alaska Airlines jet to arc their way 3,200 miles south from rainy Seattle, and land 10 hours later into the Nicaraguan night. Managua showed its presence as an indigo wrap dotted with citron lights blinking along the streets and the runway. The night air enveloped the travelers in a bear hug, as the group got its first taste of this country, where everything seems extreme—the heat, the poverty, the entrepreneurism, the graciousness, the colors.

It’s a country dominated by trade—now mostly beef, sugar and coffee—trying to elbow its way into tourism and leave behind a past crowded with civil war, damaging foreign involvement and corrupt politicians. PLU students learned about the history of Nicaragua through a series of interdisciplinary lectures scheduled by Mulder that explored the environment, ethics and culture of a country that still struggles to provide basic necessities to its citizens. About 30 percent of the population does not have access to clean water, and 63 percent does not have access to adequate sanitation. It’s a country where Coca-Cola is cheaper than clean water or milk.

All these facts come home when the students arrive at El Limonal, home to about 1,400 people and wedged between a garbage dump, cemetery and sewage plant in northwest Nicaragua outside Chinandega. This patchwork of tarps, mango trees, steel corrugated roofs and slate-colored cinder block was supposed to be a temporary camp for refugees fleeing from Hurricane Mitch in 1998. But now, nearly 17 years later, the camp is still here.

“Many of the children get sick or die because of the smoke (from the dump) and the water,” says Oscar Corea, director of Wings of Eagles Ministry, who worked with the El Limonal church and helped connect the village with Living Water.

Power is sketchy at best and has a tendency to flip on or off, and the same holds true for water: Corea says the villagers have water in their spigots at 2 a.m. on Thursday mornings, maybe.

“There isn’t enough water for everyone in Chinandega and the outlying areas, so they rotate (the water) through the districts,” he says, raising his voice over the growl of the drill.

Did You Know?

82%

of the population of Nicaragua lives on less than $1 a day.

30%

of the population of Nicaragua does not have access to clean water.

63%

of the population of Nicaragua does not have access to adequate sanitation.

Day Two:

El Limonal,

Nicaragua

Church Courtyard

Depth:150Feet

Watching the progress of the well has become a village pastime, as children and adults drop by the church courtyard. Two of the villagers have a front-row seat, since their compound sits right across from the work. Anna Marie and Nicholas Mendoza have lived in El Limonal for 15 years. Nicholas works in the dump each morning, even though he’s pushing 65, and Anna Marie sells vegetables. They also have four pet dogs and a prized hen, which is also leashed and collared so she doesn’t wander off.

“Are they going to share the water with people who aren’t in their church?” she asks through Alessandra Zeka, the PLU team’s photographer, videographer and impromptu interpreter.

I tell Anna Marie that Living Water has assured us that part of the deal with the minister is that he must share the water, without caveat, with the entire community. Living Water is not in the business of setting up local water czars, Varela says. Living Water staff checks back on the communities about every six months to make sure the water is being shared equitably and that the pump continues to work.

“This is a gift from God to this entire community,” Anna Marie says. “We would rather have this than light, because when you don’t have power you can light a candle. When you don’t have good water, what are you going to do?”

Did You Know?

2.5 billion

people on the planet do not have access to improved sanitation.

1 billion

have no access to any sanitation facilities.

783 million

people lack access to clean water.

2.2 million

deaths per year due to water-related diseases.

700 thousand

children die each year from diarrhea due to lack of access to clean water or adequate sanitation.

Day Three:

El Limonal,

Nicaragua

Church Courtyard

Depth:150Feet

It’s been two hours since the new pump was due to arrive. But we’ve adapted to both the heat and to “Nica” time.

“It was amazing, and heartbreaking both, that they’d do that for us,” she says.

Stallard, who is again covered with mud, said friendships have developed easily on this trip, despite the language barriers.

“Even though we are separated by thousands of miles, grown up on two different countries and with different backgrounds, to be able to connect so easily was shocking,” he says.

An old van rumbles up the main El Limonal street, where the sun seems to bounce off the mud and church walls. Once it arrives, a few pulls and coughs, and the pump shudders to life.

Even though we are separated by thousands of miles, grown up on two different countries and with different backgrounds, to be able to connect so easily was shocking.

The PVC pipes are inserted, and the well base and top are quickly assembled. The well is flushed with water in a gigantic surge, which in turn releases muddy water into the main street. The bystanders let out an involuntary cheer as the water turns from black to brown to clear in about two hours. A smell of mud and dampness cuts through the air.

Day Four:

El Limonal,

Nicaragua

Church Courtyard

Depth:150Feet

A few hours later, it’s time to leave. Shadows stretch long fingers across the road in front of the church, tickling at the courtyard where the well sits. Then, with a flash of turquoise cinder block, mango and smoke, the well disappears from view. Usually on the van ride back to Leon, voices ricochet inside with talk of movies, the children, new friendships, how the glitter exercise went or how far the drilling went down that day. Today, it’s silent.

Back in Tacoma

Ten hours after the plane leaves Nicaragua, the team returns to the Northwest and 50-degree weather. A cool rush of air greets us as we leave the airport. It’s been raining all week, and there’s water everywhere.

Reflecting on the trip later from an alcove at PLU’s Anderson University Center, Kaitlynn Cory ’15 said the trip has changed her life and her outlook on even the smallest details. She can now look at the not-so-perfectly-timed arrival of a church group bearing shoes for the village, just before the well was dedicated, with a bit of humor and reflection.

“I guess we prayed the day before for shoes for the village, and we talked to them about the importance of shoes just the day before and the next day … shoes,” she laughed wryly. “I didn’t expect that prayer to be answered so fast.”

As for her own reflections, she winces when her fellow classmates ask whether she had fun.

“Short answer would be no,” she says: One-hundred degree heat; the uncertainty of drinking water even at the Living Water compound; the dire poverty of the villagers—none of that classifies as “fun.”

“I guess the word that comes to mind is ‘beautiful,’” she muses. “Even the hard parts were beautiful.”

As for herself, Cory says the trip left her with a sense of gratitude—for water, of course, but also for the education, sense of mission and opportunities she receives at PLU. Just turning on the tap and seeing drinkable water come out is a gift. She also has a renewed determination to make a difference in the world once she graduates.

“I will never say I’m a poor college student again,” she laughs.

Sure, the water crisis can seem overwhelming, and so can challenging and changing poverty, in the U.S. and overseas. But she’s determined to try.

“It would be a real disgrace to come back and do nothing,” she says.