Jessica Spring knew the perfect catchword existed. She has a photograph of it — three letters, cast together on one decorative body of metal. The catch? She had to sift through thousands of pieces in dozens of type cases to find it.

A tiny word, “the” — a half-inch square among an expanse of metallic fonts. But, this wasn’t just any “the;” it was the perfect “the.”

“I confess getting a wee bit fixated once I get an idea,” Spring said of her printmaking process.

Thankfully, her fixation didn’t get too carried away. After moving on with her project using a less-than-perfect alternative, she stumbled upon the piece she longed for.

“Of course, it was too small after all that,” she quipped. “It’s either patience and endurance or we are crazy. I’m still not sure.”

Thousands of keystrokes on a laptop fall short of capturing the essence of the Thorniley Collection of Antique Type, which arrived at its new home on Pacific Lutheran University’s campus earlier this year in the form of a massive donation from WCP Solutions, formerly West Coast Paper.

The collection of typefaces, printing presses and more — which appraised at $311,330 — has elevated PLU’s printing collection to the largest in the Pacific Northwest.

“The best comparison is really the needle in a haystack,” Spring said of her persistent search for the perfect “the” within the vast collection.

It took several 53-foot trucks to transport 43 cabinets filled with 24 cases each — amounting to millions of pieces of type that span centuries.

“It’s a museum dedicated to the art of the book,” said Mare Blocker, visiting assistant professor of art and design. “It’s a labor of love for the two of us.”

The other half of the loving duo is Spring, another visiting assistant professor in the department, who serves as manager of the Elliott Press. For three decades, PLU’s small private press in Ingram Hall has provided a hands-on workshop for students in the Publishing and Printing Arts Program (PPA).

“The Elliott Press was already an interesting complement in our department. Thorniley magnifies that,” said Heather Mathews, chair of art and design at PLU. “The press is a nice juncture between concerns of design and concerns of studio disciplines. This donation amplifies that significantly. The possibilities for students are that much greater.”

Spring says the addition of the Thorniley Collection builds upon PLU’s commitment to printmaking and book arts in the greater Tacoma community.

“Now we have type and presses of the same time period,” she said, showcasing a continuum of some of the earliest type to digital type. “It’s one thing to read about it, but to actually work with it, that’s pretty incredible.”

Solveig Robinson, director of the PPA program and associate professor of English, said the collection came to PLU “because we’re special.”

“We’re still the only program in North America that combines pre-professional studies, history of the book and publishing arts,” Robinson said. “We work closely with (the School of Arts and Communication) and English to make sure students are well rounded.”

Robinson vividly recalls the first time she saw the Thorniley Collection at its previous home at WCP Solutions in Kent.

She stepped into the room, sunlight glistening off the cabinets, and was struck speechless.

“People had known it was out there, but nobody knew how big it was,” Robinson said. “We absolutely stopped in our tracks. I just gasped.”

Spring invited Robinson that day in 2016, and neither of them anticipated at the time that roughly 90 percent of what they saw would eventually sit in the Wekell Gallery in the back of the PLU arts building.

But Teresa Russell knew for some time the collection needed a new home.

Elliott Press

Founded in 1982, the Elliott Press is a hands-on workshop for students in PLU’s Publishing and Printing Arts (PPA) Program and for others interested in the history and artistry of the printed word.

Russell is the third-generation owner of WCP Solutions and the daughter of Dick Abrams, who purchased the antique collection from its originator, William Thorniley, a friend and fellow printing arts enthusiast.

Russell said WCP has needed the space occupied by the collection for roughly five years.

“I didn’t want to sell it,” she said. “It didn’t seem right.”

Perfect home

Thorniley started his collection in 1909, after receiving his first printing press at the age of 10. Over time, as he traveled for work on the lookout for type, Thorniley’s collection grew to include pre-Civil War pieces from the deep south, Gold Rush-era fonts from California and discoveries spanning from Alaska to New England.

When Thorniley started to scope out opportunities to relocate his collection, he turned to Russell’s father. He initially courted the Smithsonian Institution, but the talks broke down. Ideally, Thorniley not only wanted to keep the collection in the Pacific Northwest, he wanted the new owner to use it.

So, Abrams purchased the collection in 1975. It stayed in Thorniley’s basement until he passed away in 1979. Russell said the crew in charge of moving it for her father had to take out a wall to remove all the pieces. “I would’ve liked to see that,” she said, laughing.

During its time with the paper company, the Thorniley Collection was used sporadically by locals of all ages. Students from elementary schools, Highline Community College and the University of Washington worked with the antique typefaces and equipment.

But Russell said use was infrequent. “It was treated more like a museum,” she said.

Now, PLU is expected to use the equipment regularly — more than it’s been used since Thorniley’s time.

“This is very intentional,” Russell stressed. Otherwise, she noted, pieces could rust or presses could freeze up.

Russell credits Carl Montford, a Seattle printer who restored one of the collection’s hand presses, with connecting her to PLU. “Carl introduced me to this book arts community in Tacoma,” she said.

Russell said PLU is the perfect home for the Thorniley Collection, and not just because the university made room for it. She said stewards at PLU have the expertise to know what should be on general display, what should be locked down and what pieces can be used daily.

Despite the obvious fit, Russell says she never anticipated the level of emotion the Thorniley Collection has inspired among Robinson, Spring, Blocker and others at PLU.

“I hope it’s used to teach and inspire another generation of craftspeople,” Russell said.

“And I hope it’s used in a way that preserves it.”

Endless discoveries

Blocker and Spring are hard at work cataloging Thorniley items, with the help of PLU students across many academic departments. The sooner they can organize the collection, the sooner they can open it up to the public, with the appropriate guidance and supervision.

Spring said it’s easy to spend hours in the gallery rummaging through type cases and inspecting the detail in the cuts and tiniest pieces of type.

“Every day is a new discovery,” she said.

The core of the collection is Victorian, but it includes more recent additions by Pacific Northwest printers that resulted in a continuum of the history of type.

“They all have stories,” Blocker said of each piece. “It’s pretty cool.”

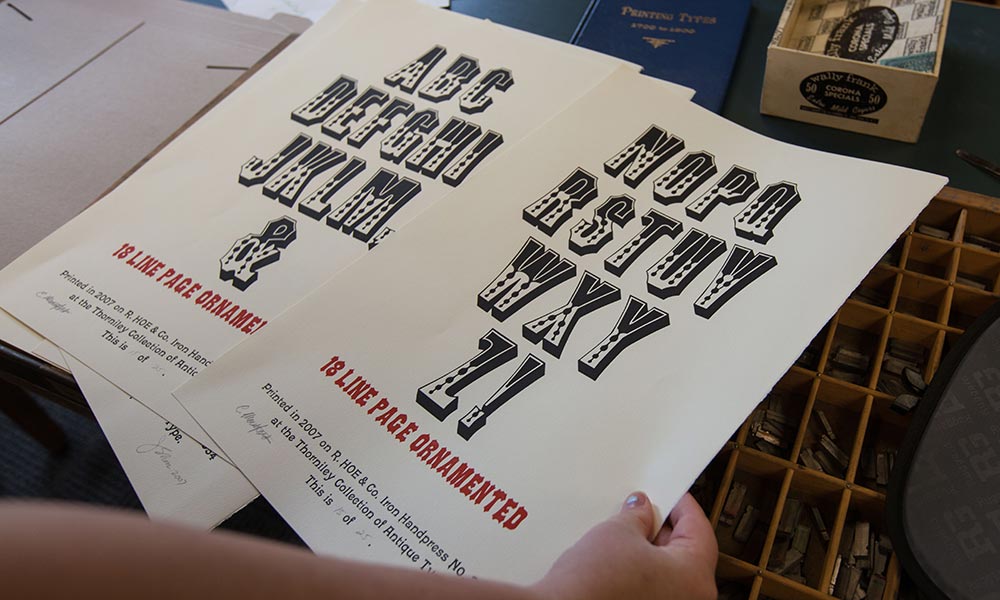

Spring said many of the typefaces date back to the era defined as “artistic printing,” marked by ornamental type, unusual compositions and quirky embellishments used to create ephemera of everyday life.

Among the collection’s stars, she said, is a Washington Hand Press, the first iron hand press manufactured in the U.S. The collection also includes a Die-Engraving Press and steel dies, mostly monograms. The tools are used in a process known as stamping, or embossing. In addition, the collection includes one of a limited number of No. 2 Potter Proof presses that dates back to the early 1900s.

The collection also features wood and metal type — more than 1,300 typefaces introduced between 1690 and the 1930s. The metal type was cast in U.S. and European foundries, and features pin marks of origin — simple logos on the body.

The oldest types in the collection include Union Pearl, the oldest decorative English typeface that dates back to 1690; Harlequin, circa 1770; and Caslon Oldstyle, which belongs to a family of types distributed throughout the British Empire, including British North America where they were used to print the Declaration of Independence.

Some of the collection’s oldest type was cast in unusual sizes, pre-dating the industry’s effort to standardize toward the end of the 19th century.

Notable wood typefaces include Art Gothic, which debuted in 1887 with mixed reviews, and Mikado, some of which is celluloid and especially rare since the enameled pieces were only manufactured for roughly 15 years.

Also included in the wood type are a few chromatic faces, which were made to print two or more colors in tight register. And one incomplete font of 72-line type measures a foot tall.

The collection also came with typefaces in other languages, such as Chinese, which Blocker and Spring say likely will be incorporated into interdisciplinary education.

“A lot of this is super rare, a lot of it is in really good condition, and then there’s the sheer volume,” Blocker said.

The collection also serves as a resource for graphic designers. PLU’s Boge Library, which holds books on the history of calligraphy and typography, now houses some of the rarest type as well as an array of antique finishing tools for bookbinding.

More than a museum

The Thorniley Collection will not only invite PLU students from varying disciplines to learn about printmaking, but also members of the community.

Blocker is working to develop a summer program for Pierce County kids and their teachers. She wants local students to learn about book arts, and she hopes to show teachers how to incorporate printmaking and the art of the book into K-12 education.

Spring said the nonprofit Guild of Book Workers also will bring its annual conference to PLU in response to the relocation of the collection, to tour the Elliott Press and learn more about the Thorniley additions.

Dave Tribby, a longtime donor to the Elliott Press who lives in California, is an active member of the national organization American Amateur Press Association. He didn’t know about the Thorniley Collection until it came to PLU. Upon further research, Tribby said he’s excited to see it go to such a well respected printing arts program for regular use by the public, as opposed to sitting in cases at a museum.

“To be able to see the actual artifacts from that era when they were created, and not a modern reproduction, that’s interesting,” Tribby said.

Robinson hopes the major donation will attract others, including funds that could lead to a newer, bigger campus building to house the Thorniley presses and type. She estimates the donation of the collection — which rivals some she’s seen in museums in Europe — has at least quadrupled PLU’s letterpress resources.

“We should be a magnet for more,” Robinson said. “The more you have, the more you draw.”

In the meantime, PLU students in PPA and graphic design classes have already started using the collection for printing projects. Robinson says she’s excited that students who are interested in the history of the book can see and work with type and presses described in their textbooks.

“It’s a museum dedicated to the art of the book. It’s a labor of love for the two of us.”

– Mare Blocker

“It takes them back in time, as opposed to reading about it,” she said. “You can see how the styles and technology have changed. I am so overwhelmed that these are available to our program.”

Russell, the donor praised by so many at PLU, says printmaking is a nostalgic art that she hopes will continue to thrive in Tacoma and beyond.

“No matter what you do digitally, there’s no tactile feel to it,” Russell said.

She believes the Thorniley Collection could create a central hub at PLU — a focal point that is missing in the local printing arts community. Russell said the collection has potential to add vitality to PLU’s already renowned program.

“Word is out,” she said.

No matter its potential for growth, the collection already provides endless possibilities for students and artists at the university, Spring said.

“Printers use the term ‘out of sorts’ when we run out of letters,” she said. “We won’t ever again at PLU.”