Faculty Proudly Wear First-Gen Experience

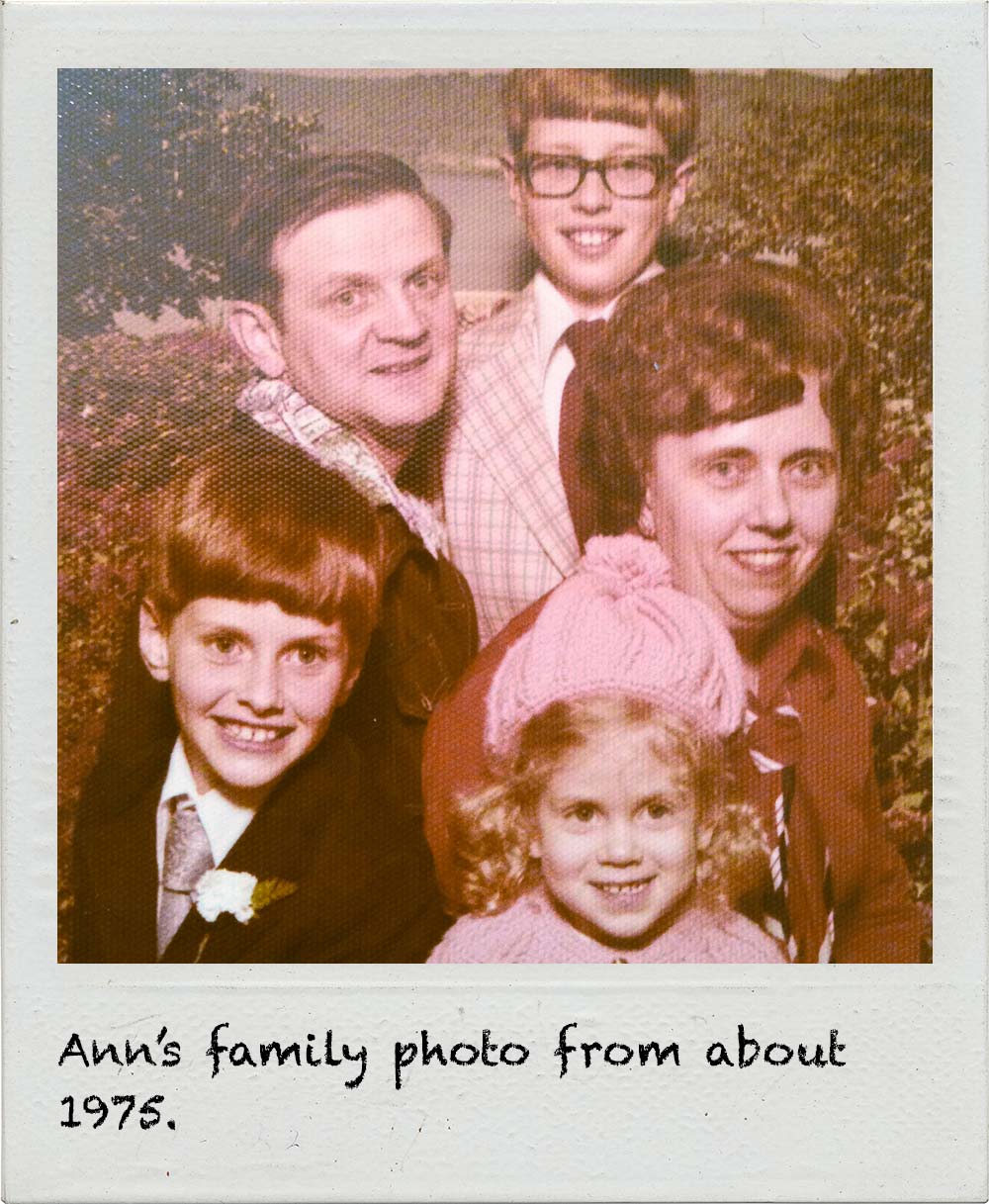

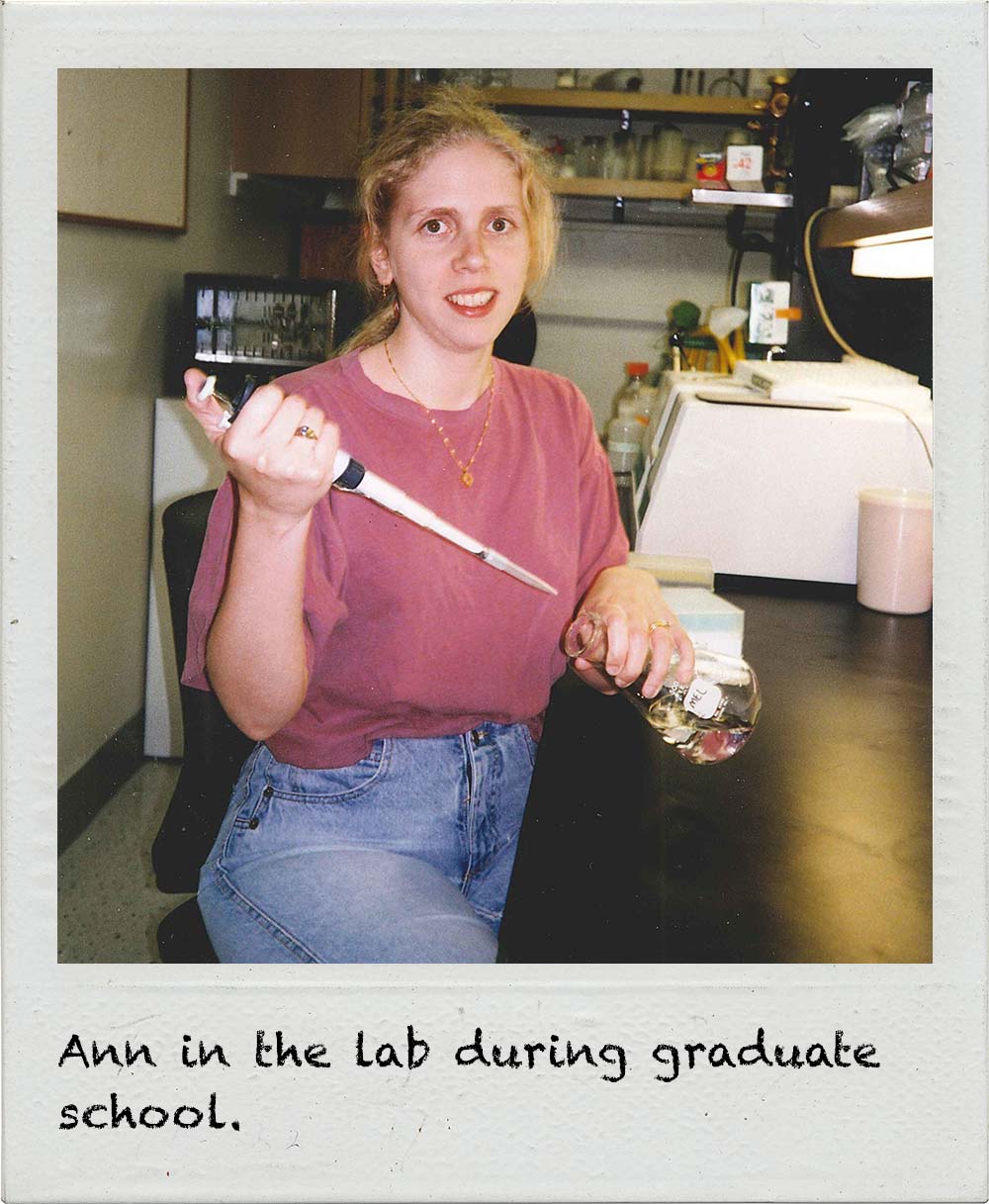

Ann Auman didn’t always publicize that she was first in the family to attend college. In fact, before Pacific Lutheran University started prioritizing the first-generation student experience, it rarely crossed her mind.

Now, the dean of natural sciences wears it on a button — during new-student orientation, move-in day, even at events where prospective students might surface.

“For a long time, I didn’t really think about being first-generation,” said Auman, who also serves as professor of biology. “It’s not like I put that label on myself. In more recent years, as PLU has put more of an emphasis on trying to support first-generation students, I obviously recognize that I am one.”

The button that Auman and roughly 60 faculty and staff members across campus wear carries a simple but profound declaration: “Proud to be first in the family.” It serves as a conversation starter, signaling to current first-generation students that these members of the community can offer guidance from the perspective of someone who has walked in their shoes.

And in Auman’s division alone, there are a lot of those shoes. Several biology faculty members — many of them women, a group traditionally underrepresented in the field — claim a first-generation background.

Proud to be first

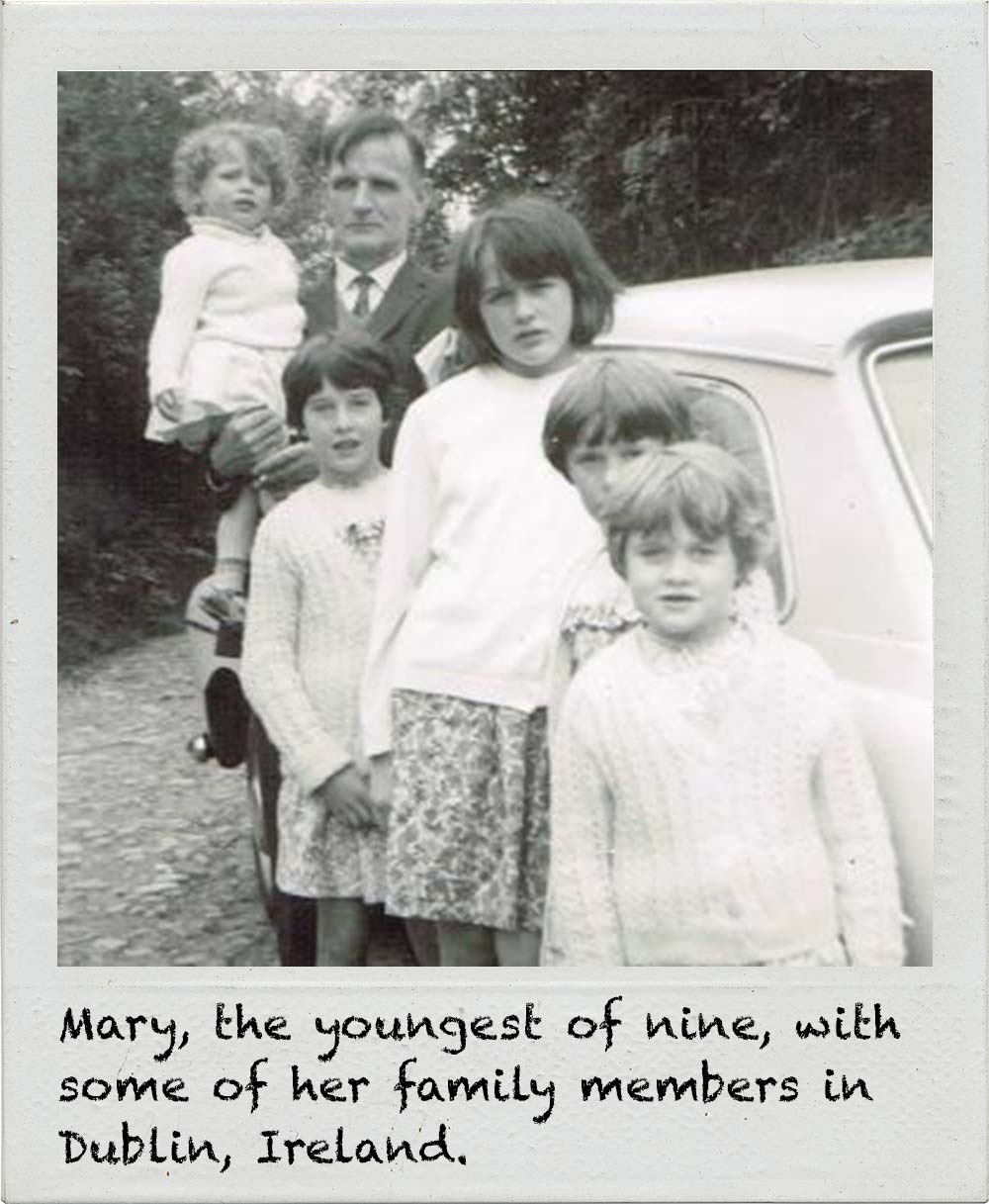

For Mary Ellard-Ivey, professor of biology, the courage to pursue her college dreams started with a teacher’s simple checklist.

“I had a high school biology teacher who I remember very fondly as really encouraging me to go to college,” said Ellard-Ivey, who grew up in working class Dublin, Ireland, as the youngest of nine children. “He said I didn’t need anything except a bicycle and a pen and paper. And I already had a bicycle.”

Her parents, on the other hand, were skeptical when she told them she wanted to be the first in her family to graduate from college.

“I understand now that they were coming from a place of extreme concern,” said Ellard-Ivey, who has taught at PLU since 1997. “It doesn’t mean they didn’t want what was best for me.”

Still, she remembers her mother’s reaction: “You have ideas above your station, young lady.”

As Ellard-Ivey would discover, it’s not easy being first.

Students whose parents or siblings have not attended college face significant hurdles when they choose higher education. Many not only lack cash, but they also may be deficient in the kind of social and cultural capital that their peers with college-educated parents gain as a birthright.

Everything from selecting a college to filling out applications, from choosing electives to choosing a meal plan can be a bigger challenge for first-generation students who have no one at home to offer advice based on personal experience.

And once they clear the big hurdles — gaining admission, securing scholarships and loans — first-in-the-family students may find themselves on campus struggling with the feeling that they don’t really belong there.

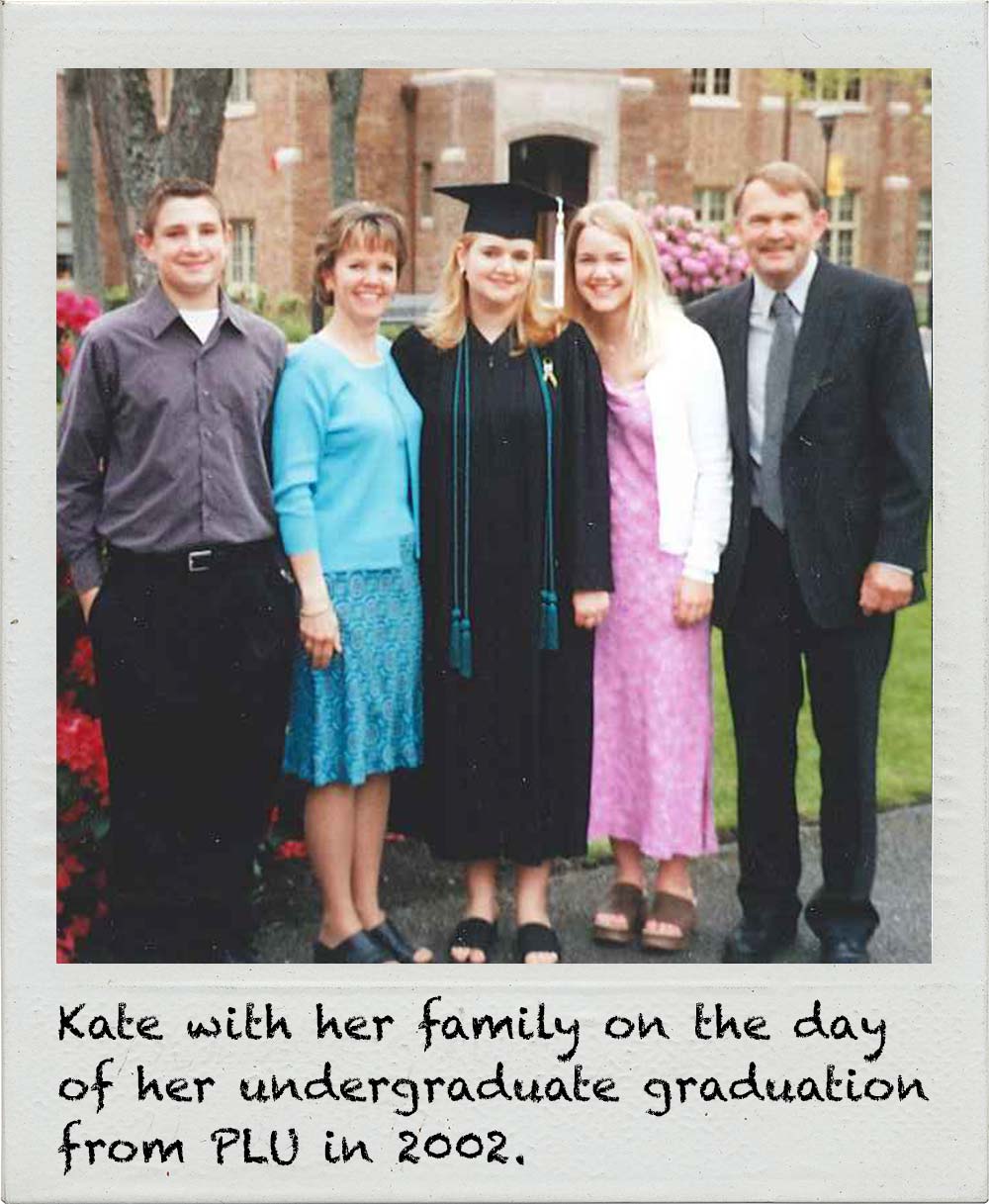

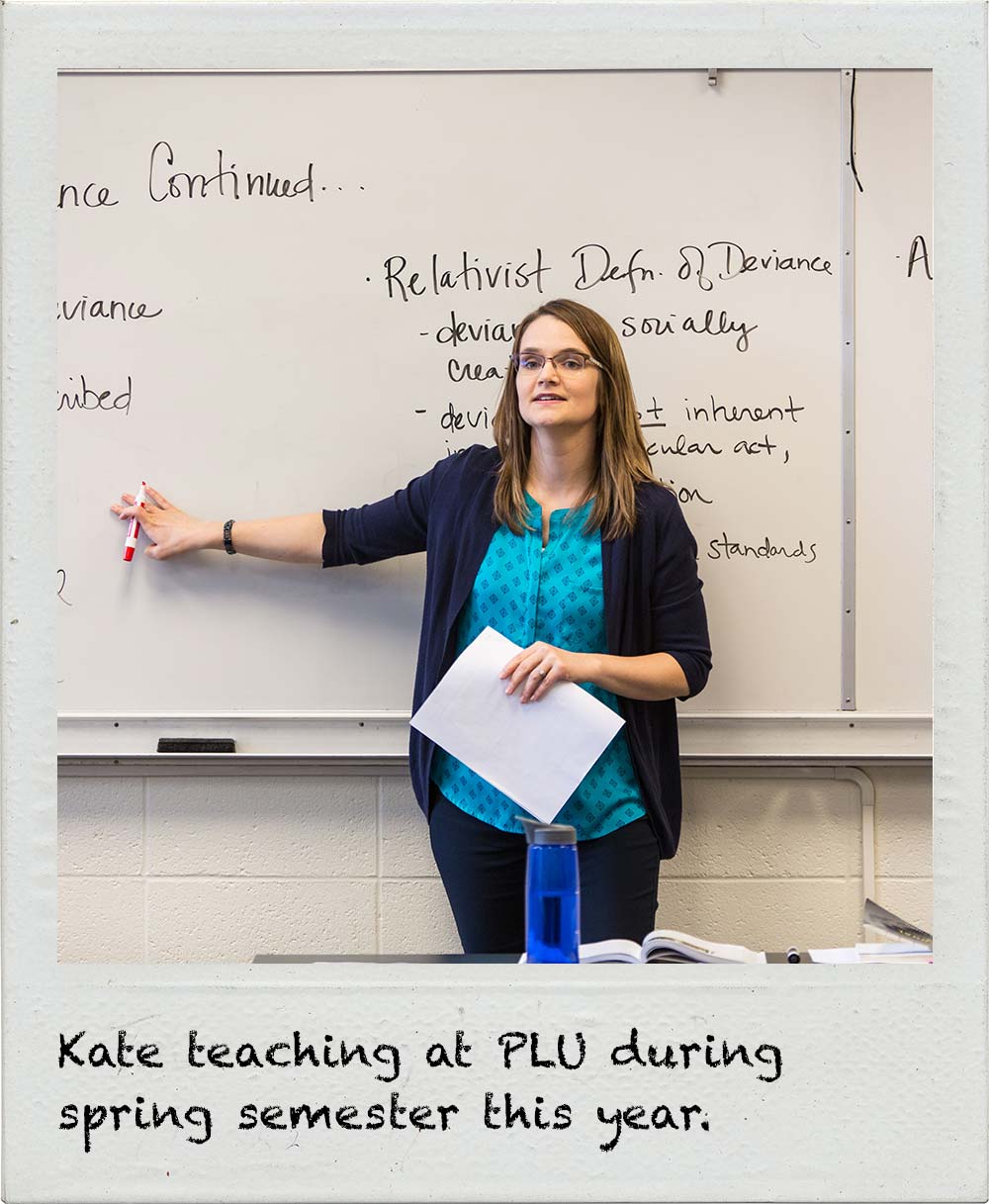

Kate Luther ’02, who chairs the PLU Department of Sociology, got both financial and emotional support for college from her family, as well as a financial aid package from PLU. She graduated with a degree in sociology and psychology, then went on to earn her master’s and Ph.D. in sociology at University of California, Riverside.

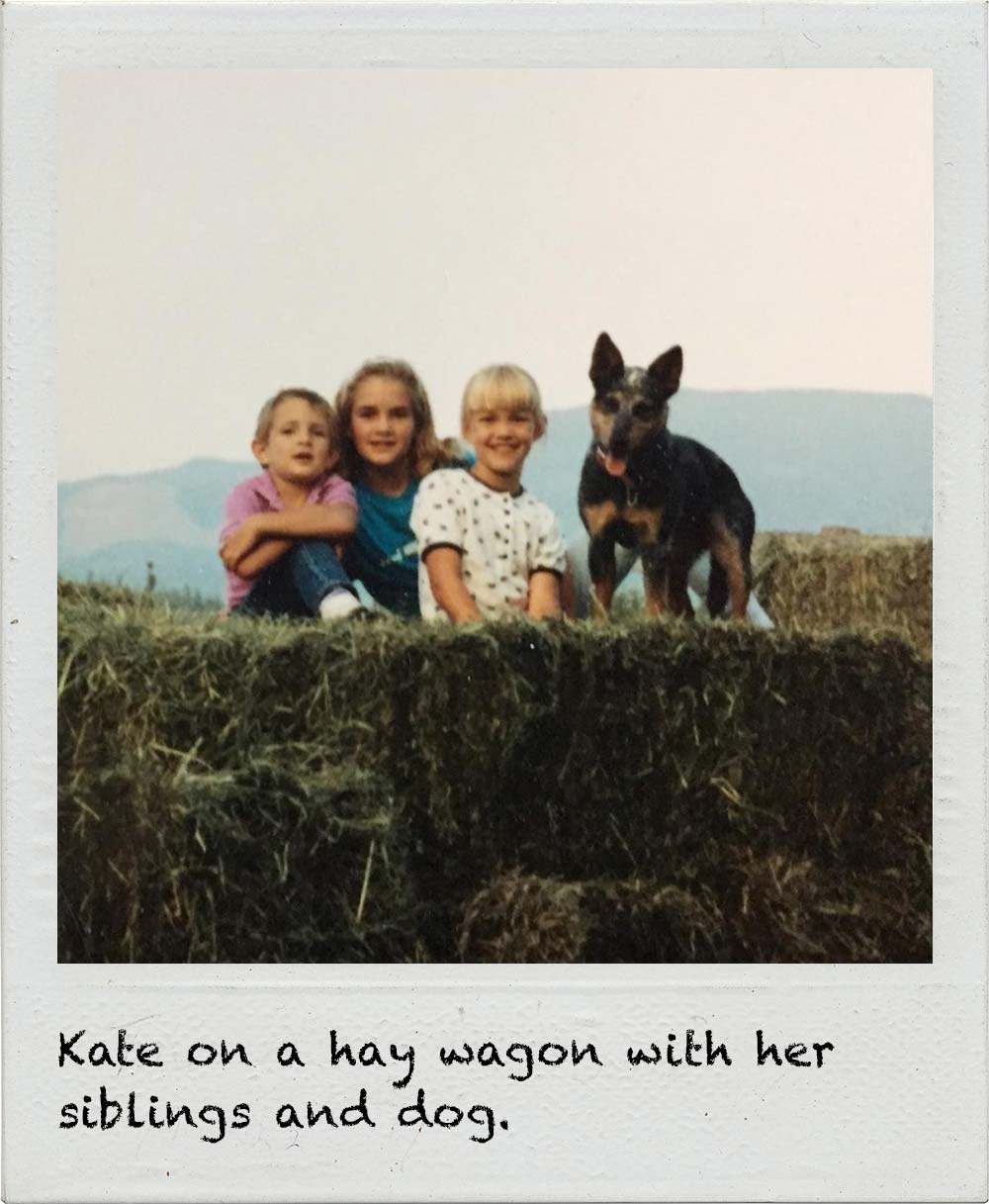

“My parents always wanted me to go to college,” said Luther, the oldest of three siblings and the first to attend college in her family. Her parents — a homemaker-turned-paraeducator and a carpenter who rose to become a construction supervisor — had saved a college fund she could draw on.

But she also worked a variety of summer jobs, including as a waitress at the local diner in her small hometown of Everson, outside Bellingham, Washington.

It was the proverbial one-stoplight town — actually, a flashing light — when Luther was growing up.

Luther realized once she got to college that “my friends’ families had different educational levels, and their families knew things that my family didn’t know.”

Now, she tells her first-generation PLU students that they are just as well loved by their parents as any other student.

“But we have to figure out how to do this on our own, in ways our peers do not,” Luther said.

PLU tries to bridge the knowledge gap with programs for students that include a First in the Family community in Stuen Hall and other forms of assistance.

And in fall 2017, the university’s Center for Student Success, the Diversity Center and Residential Life launched a campaign to help faculty and staff show support for first-generation students.

That’s when Auman and others started proudly wearing their first-in-the-family buttons. Acting President Allan Belton wore his throughout beginning-of-the-year festivities — a gateway into sharing his own first-generation story. He centered his speech at University Conference — which kicks off the academic year — around his experience being first.

Representation from the beginning is key, which is why Auman keeps her button at the ready.

She has seen the struggles of students who may be juggling school, home life and even children of their own. And she’s glad that she can call on the campus Student Care Network to offer comprehensive support and necessary resources for navigating higher education.

Auman remembers what it was like in her student days, in an era before cellphones, when she had to time her calls home to her parents on Sunday nights after 9 p.m. That’s when the long distance phone rates were cheaper.

Money was tight, especially after the closure of the department store where both her parents worked.

Auman survived her undergrad years on scholarship money and a system known as co-op education, which allows students for part of their college experience to alternate studying a semester and working a semester in a degree-related field. Her earnings from co-op work in a pharmaceutical company helped pay for college costs.

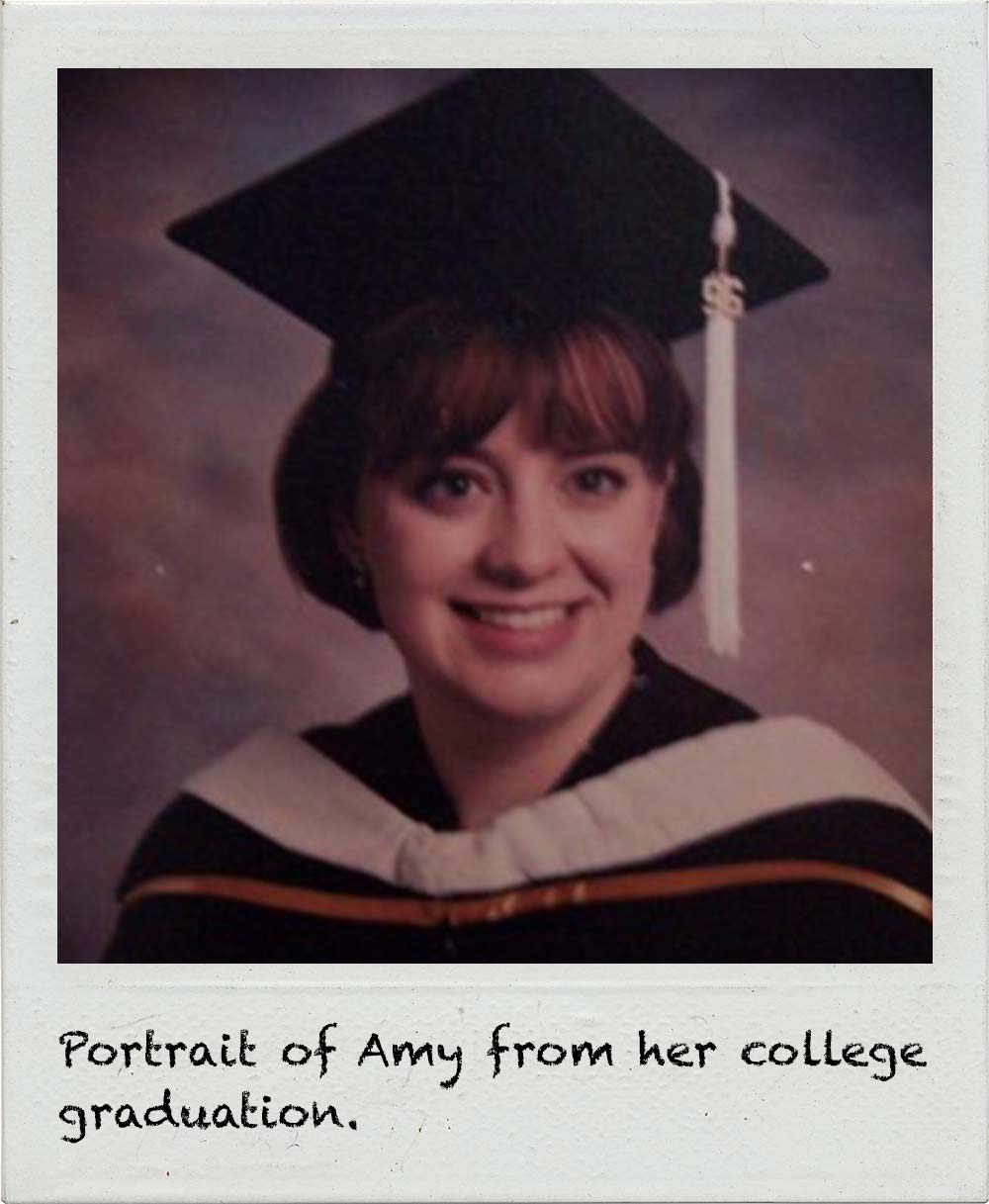

“I went to a really big school,” said Auman, who attended Penn State University for her two undergraduate degrees and the University of Washington for her Ph.D. in microbiology. “I could have slipped through the cracks really easily and nobody would have noticed.”

First comes with fortitude

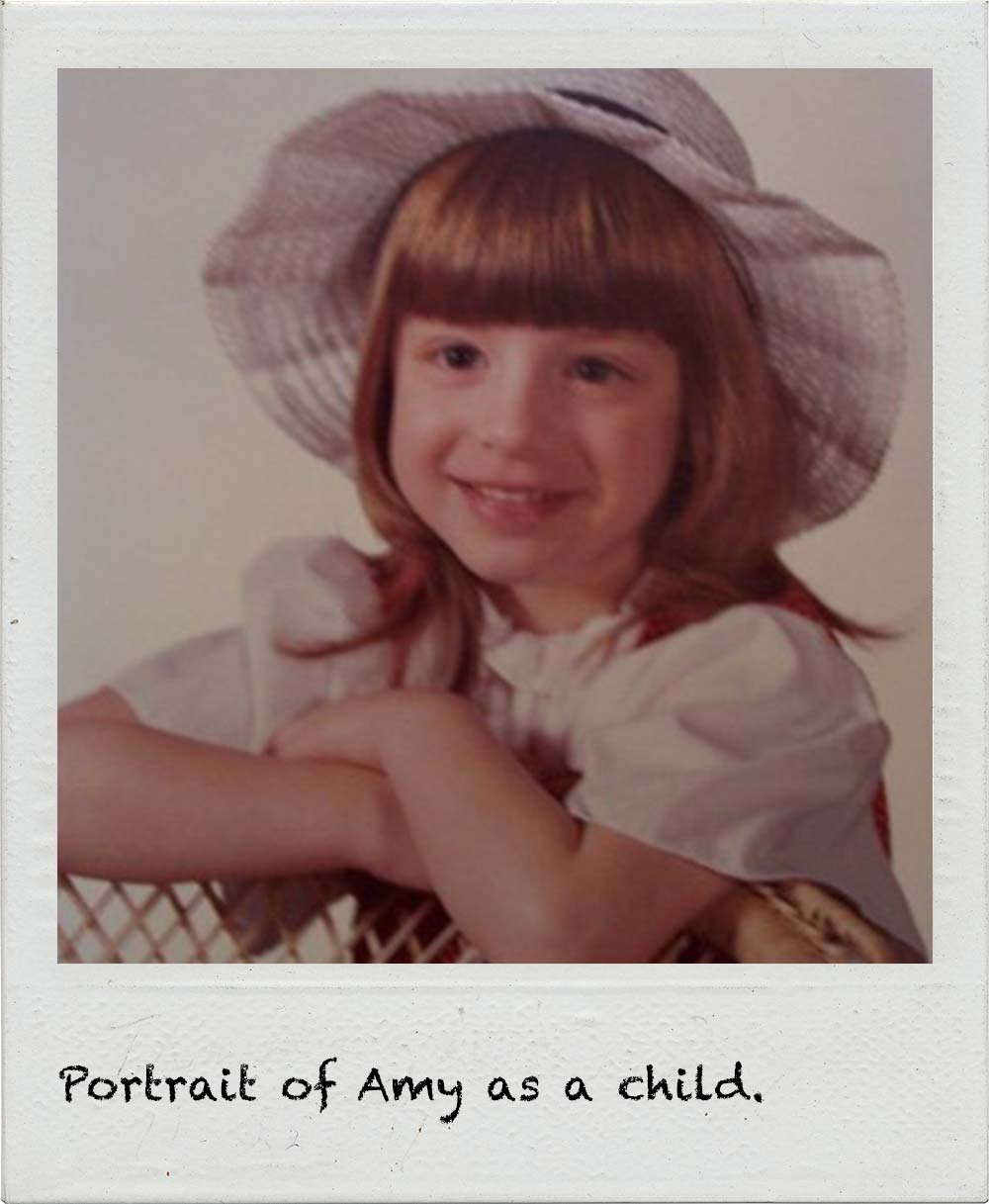

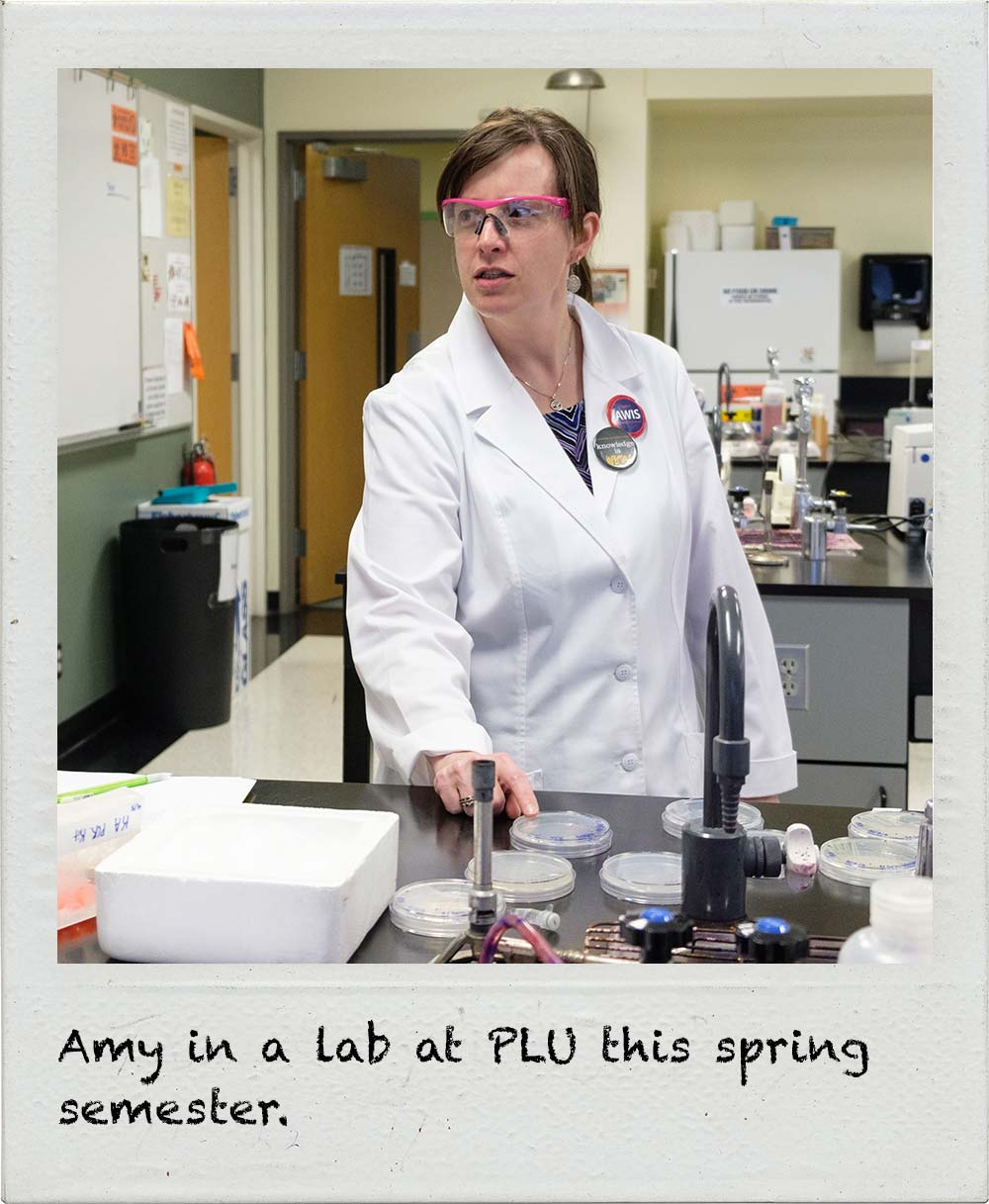

Growing up in rural Wisconsin, Amy Siegesmund didn’t hear many of her peers making college plans.

As the oldest of three children, she doesn’t remember her parents being against her going to college. But Siegesmund, now an associate professor of biology at PLU, doesn’t remember them actively pushing the idea, either.

Her inspiration came from her circle of friends.

“It was the group I hung out with,” she said. “We decided to do it together.”

Like many first-generation students, she relied on a combination of student loans and work to finance her education at Alverno College, a small liberal arts college in Milwaukee where she earned a degree in biology. She received her Ph.D. in microbiology from Washington State University.

“I had all sorts of retail jobs,” Siegesmund said of her college years. “I also had a job on campus. Part of my financial aid was a work-study job in the library. I loved that job. For the last couple years of school, I was working close to full time.”

Siegesmund said leaving her small Wisconsin town for the big city, living on campus and being exposed to the life-changing power of education was worth the struggle.

“Discovering ideas about new ways of thinking and ways of exploring questions — it was transformative for me,” she said.

Siegesmund says that when her PLU students spot her wearing her first-in-the- family button, it opens up all kinds of conversations.

Some who live on campus, but have family close by, feel the pull from home — parents who expect them home on weekends, when students are trying to make connections on campus.

“Their families don’t always understand how much time it takes to be a student,” Siegesmund said.

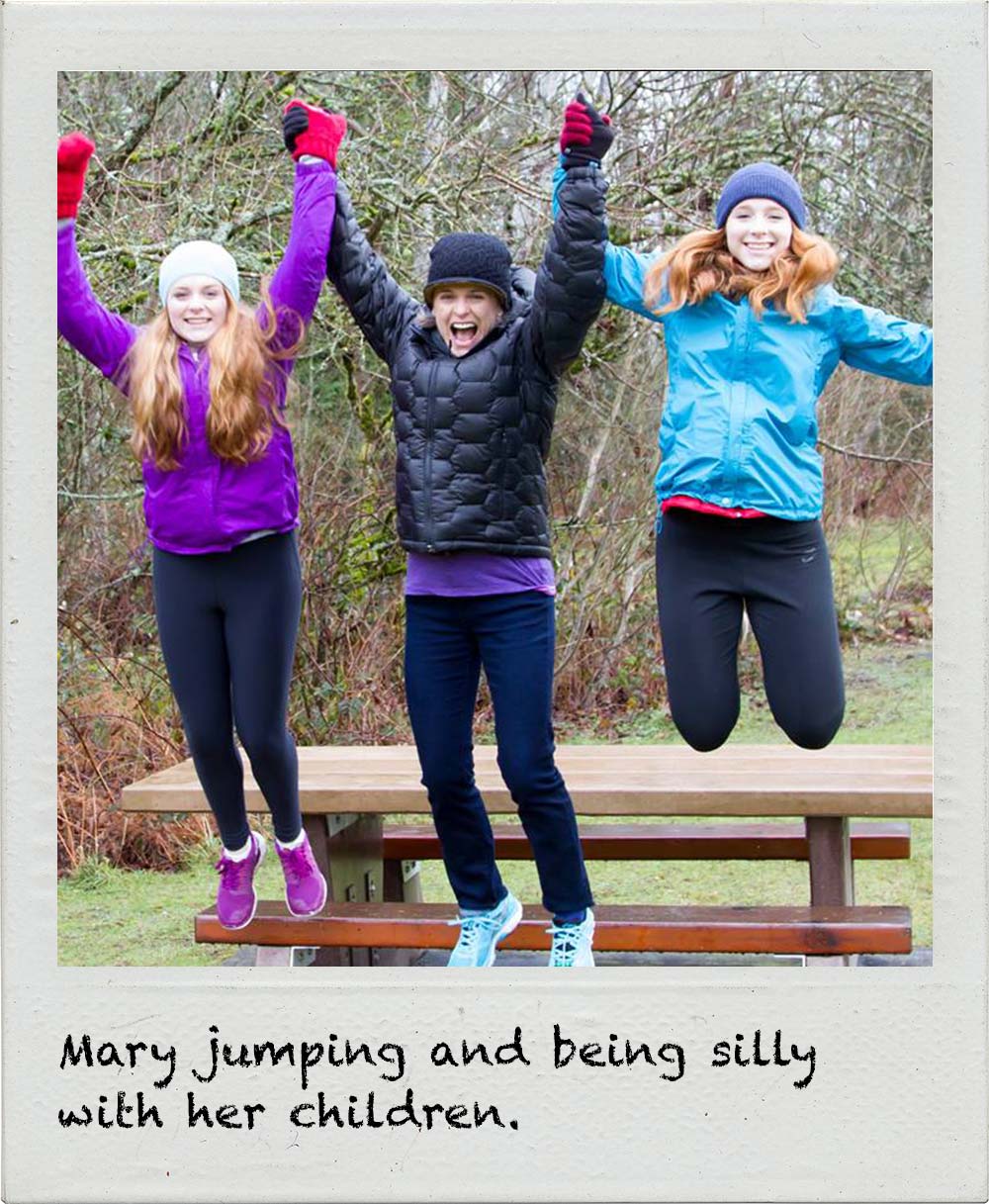

Ellard-Ivey said her first-generation students sometimes worry that their families don’t understand what they’re doing at college.

“That was my experience,” said Ellard-Ivey, who attended University College Dublin for her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in botany and earned a Ph.D. in molecular biology at the University of British Columbia.

One experience she doesn’t have in common with her American students is their financial struggles. Ellard-Ivey lived at home while she attended college in Dublin with a government grant that paid for her tuition and books. She worked one day a week at a hospital switchboard and commuted by bicycle.

“One of the things that blows me away about the United States is the lack of support for (higher) education,” she said, noting that most European countries provide much more. That support, she said, ensures that college is “not a luxury for the privileged,” but available to anyone with the “need, motivation and ability to go to college.”

She talked about a recent interaction with a student, who was torn between attending an important guest lecture on campus and missing time at her job.

“I know it’s difficult for them,” she said of her first-generation students. “I’m in awe of some of the fortitude I see. They bring with them a type of motivation that I admire.”