– Estudiantes de español como lengua heredada celebran nuevas experiencias juntos

Emily Davidson ’98 pursued the study of Spanish, in part, to prove herself to her grandmother.

“I wanted to prove to her that I was really Latina,” she said, with a laugh.

Davidson, now an assistant professor of Hispanic studies at Pacific Lutheran University, says many of her college experiences — including traveling by herself to her mother’s home country Panama after graduation — were motivated by a desire to show her family she was authentically one of them.

“For me, it was important in developing my identity to fully develop my language skills,” she said.

That self exploration informs how Davidson educates her bilingual students, who take the “Spanish for Heritage Speakers” courses she launched at PLU. All of them grew up speaking Spanish at home.

“Each family has a different dynamic,” Davidson said. “In some homes, they speak all in Spanish, but in most, you might speak Spanish to grandma, code-switch between English and Spanish with your parents, and speak Spanglish and English with your siblings.”

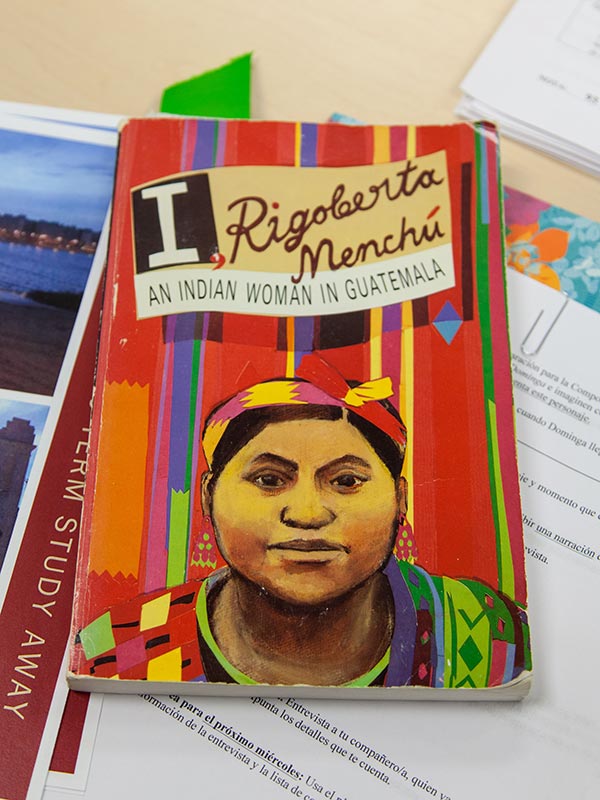

During a recent discussion with the spring-semester class, Davidson jotted bullet points across a whiteboard about the assigned reading “I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala.” In the testimonial — written in many world languages, including Spanish, despite the English title used in class — the Nobel Peace Prize winner reflects on her experiences as an indigenous woman in Guatemala amid political terror and genocide.

Davidson challenged the students to analyze the activist’s story as part of their study of narrative. Among the contenido , the content, the students discussed:

Tradiciones indígenas ; indigenous traditions.

Eventos — ella como testigo ; events as Menchú witnessed them.

Descripciones de la violencia ; descriptions of the violence.

Historias personales de la concientizacíon ; personal stories of how she developed a critical consciousness (or in millennial speak, they joked, how Menchú “got woke”).

And, fittingly, género literario del testimonio ; literary genre of testimony, which privileges memories and personal experiences.

Sharing personal experiences, in many ways, lies at the heart of Davidson’s heritage speakers course series. It’s designed to pull from and empower the personal histories of the Latino students who take it — an academic approach rarely offered to them in U.S. classrooms, Davidson says.

“We get to channel our own experiences into what we write,” Sharlene Rojas Apodaca ’21 said of her class.

Empowering bilingual learners

Rojas Apodaca is one of many first-year students, past and present, to join the cohort of heritage Spanish speakers. She’s also one of many first-generation college students to enroll.

The small, seminar-style courses are designed to hone participants’ Spanish skills: academic writing, grammar, vocabulary and awareness of “linguistic registers,” or the way that language shifts based on context or communication goals. They also introduce students to the broad histories and cultures of Hispanic countries around the world, as well as the U.S.

“Unfortunately, we live in a country that doesn’t really value bilingualism,” Davidson said. “They have distinct talents that we need to help support and develop.”

Davidson designed the course series, now in its third year, as a hybrid between cultural studies and language learning. It offers bilingual students the rare opportunity to develop both languages simultaneously and in community.

It also aims to destigmatize the use of so-called “slang,” or less formal ways of speaking.

“It’s not seeing them as a population with special needs,” Davidson stressed. “It’s seeing them as a population with special skills.”

Francisco Aragón ’19 — a Mexican-American who took Davidson’s heritage speakers class his first year at PLU — appreciated that intentional approach.

“She doesn’t use Spanish to correct how you talk, but rather explains why you talk the way you do,” Aragón said, noting that it was counter to his experience taking some Spanish classes in high school.

“The goal is to empower students by establishing a greater language repertoire,” Davidson said.

The springtime discussion illustrated how students work to expand that repertoire. While discussing her view of Menchú’s testimonial, one student switched to English to clarify the translation of “terminology” (terminología ).

Beyond language, though, students embrace their culture and learn about others — addressing shared experiences, as well as those unique from their own.

“It’s an invitation to critically examine what it means to be Latino in the United States,” Davidson said.

Students in the cohorts claim a variety of backgrounds — with families from countries all over Central and South America, for example — and their majors are as diverse as they are: biology, education, philosophy, social work, kinesiology, and more.

But Davidson said their shared experiences are key to creating the sense of community, a primary factor that has contributed to the cohorts’ near-perfect retention rate, despite the challenges first-generation students of color often face coming into a predominantly white institution.

“It’s powerful when you can come together with a group of people who share similar experiences with you,” Davidson said. “It’s sort of like a homeroom. It’s a place of belonging. It’s a place where you feel like ‘everybody in here gets me.’”

Valeria Pinedo Chipana ’20, an engineering student, registered for the class in 2016 hoping for that built-in community. During her high school years in predominantly white schools in University Place, she had to branch out to surrounding Tacoma, Parkland and Spanaway schools to meet other people of color.

After joining the heritage speakers cohort, Pinedo Chipana gained so much more, particularly a heightened ability to communicate with her relatives from Peru, where she was born.

“My parents know all the history,” she said. “I was able to relate more to what they were talking about. When I learned about the history, I could finally understand what they were talking about.”

Rojas Apodaca, a philosophy and Hispanic studies double major, says her learning also extends outside the classroom. “We always talk about it in other classes and at home,” she said.

Intersecting identities

Rojas Apodaca, who was raised by a single mother and moved to the U.S. from Mexico when she was 8 years old, says her identity as a first-generation student is just as salient as her other intersecting identities.

Davidson’s cohort allows her to discuss the struggles she shares with her peers. Among them, balancing her responsibilities at home — helping with bills, working multiple jobs — with the high expectations she sets for herself academically.

“We’re all having this kind of unique, shared experience not only being first-generation, but also being Latina women and trying to get our education,” Rojas Apodaca said of her all-female class this semester. “And not having that define us, but having it be a part of us.”

Despite the challenges, Rojas Apodaca stresses the strengths she’s gained from her background. Her mother never made her or her siblings feel like they went without, and inspired them to speak success into existence. That upbringing taught Rojas Apodaca to take ownership of her future, and informs her continued path toward law school.

“She was always very motivating, and I think that transcended into my own motivation,” Rojas Apodaca said. “She’s a really good role model for me.”

Cristina Flores ’19, who is majoring in psychology with a minor in Hispanic studies, says her first-generation identity in relation to others in the heritage speakers class is complicated.

She sometimes feels like she’s “faking it,” since her mom attended some college in her home nation of Peru and her dad earned a graduate degree before becoming a systems engineer back home. Her aunts and uncles — among them dentists and neurosurgeons — also had a sense of belonging in academia and spoke the language of higher education.

Still, PLU defines first-in-the-family students as those who come from parents who didn’t study at U.S. colleges, and Flores says she shares some of the traditional experiences of first-generation students. “They are kind of living through me, in a sense,” Flores said of her parents.

She shares the strengths of fellow first-gens, too: resilience, grit, an ownership of her success.

“It’s a different kind of pressure because you, in a way, are being the pioneer to the next generation. The road in front of you isn’t paved at all, you’re the one who has to pave it,” Flores said. “Once you get across it and you’re able to look back, there is a stronger sense of satisfaction that comes with it.”

Aragón, a kinesiology and Hispanic studies double major, says he never really talked about his identity as first in the family with his heritage-speaker classmates. But, the shared experiences were still there.

“It’s powerful when you can come together with a group of people who share similar experiences with you. It’s sort of like a homeroom. It’s a place of belonging. It’s a place where you feel like ‘everybody in here gets me.”

– Emily Davidson

“There’s definitely a whole lot of framework I have to build up for myself as a first-gen student,” he said. “Really becoming my own parental figure. I know I have to be on top of things.”

And he and his peers who are blazing the trail bring a different perspective to the table, he stressed. “I think they bring, in a sense, hope,” Aragón said. “Regardless of where we’re coming from, despite all these odds, we’re willing to be dedicated to our education.”

Rojas Apodaca underscored that benefit. She said first-in-the-family students offer a dynamic perspective that helps professors improve how they teach, and PLU is better for it.

“We’re very excited to learn, we’re excited to get involved and we’re excited to participate in class,” she said. “My peers can learn from me.”

Davidson says that same excitement and pride students show for their culture is one of the most rewarding parts of the courses she’s created. And it begins with early recruiting, before students even step foot on campus their first semester.

“That’s a labor of love,” she said. “I’m a heritage speaker and I really believe in this powerful experience exploring who you are through your language in college. It changed my life and I want students to experience that. It’s very personal.”