There’s something about Laree Winer’s chair.

I knew writing a story about first-in-the-family college graduates meant talking about my parents. I didn’t think it meant crying about my mom with a colleague I’m just getting to know.

There’s a chance Winer ’15, associate director for student engagement and the Center for Vocation at Pacific Lutheran University, expected it.

“This work is emotional to me,” she said, fighting through tears, amid my poor attempt to do the same.

There’s a special kinship between people who are first in the family to graduate from college: grit, resilience, pride in where you come from, even more pride in where you’re going.

But Winer’s chair — the “vocational chair,” as people fondly call it — mustered something in me that I wasn’t expecting.

Winer witnesses many similar reactions in the chair, as she guides other first-generation Lutes through the unfamiliar territory of pinpointing their passions. For those students, “finding a calling” isn’t typically at the top of their list of college goals.

“Nobody has ever asked these questions. Nobody has given them this option,” Winer said. “This is a means to an end, instead of a lifelong journey.”

What was your path to college?

Editor’s note: This series of videos offers an in-depth look into the perspectives of six Lutes who identify as first in their families to attend and graduate from college. The pairs have developed close relationships during their time at PLU, in part because of their shared experiences as first-in-the-family students and graduates. Learn more about what makes them proud to be first.

That is until Winer intervenes. She doesn’t minimize their priorities: getting a great job, earning a good salary, making their family proud. Still, she helps the students discover the complete picture of success.

“We’ll talk about hard things. Fear. Doubt,” Winer said. “A lot of my support is helping them be courageous.”

And Winer knows firsthand what it takes to find courage.

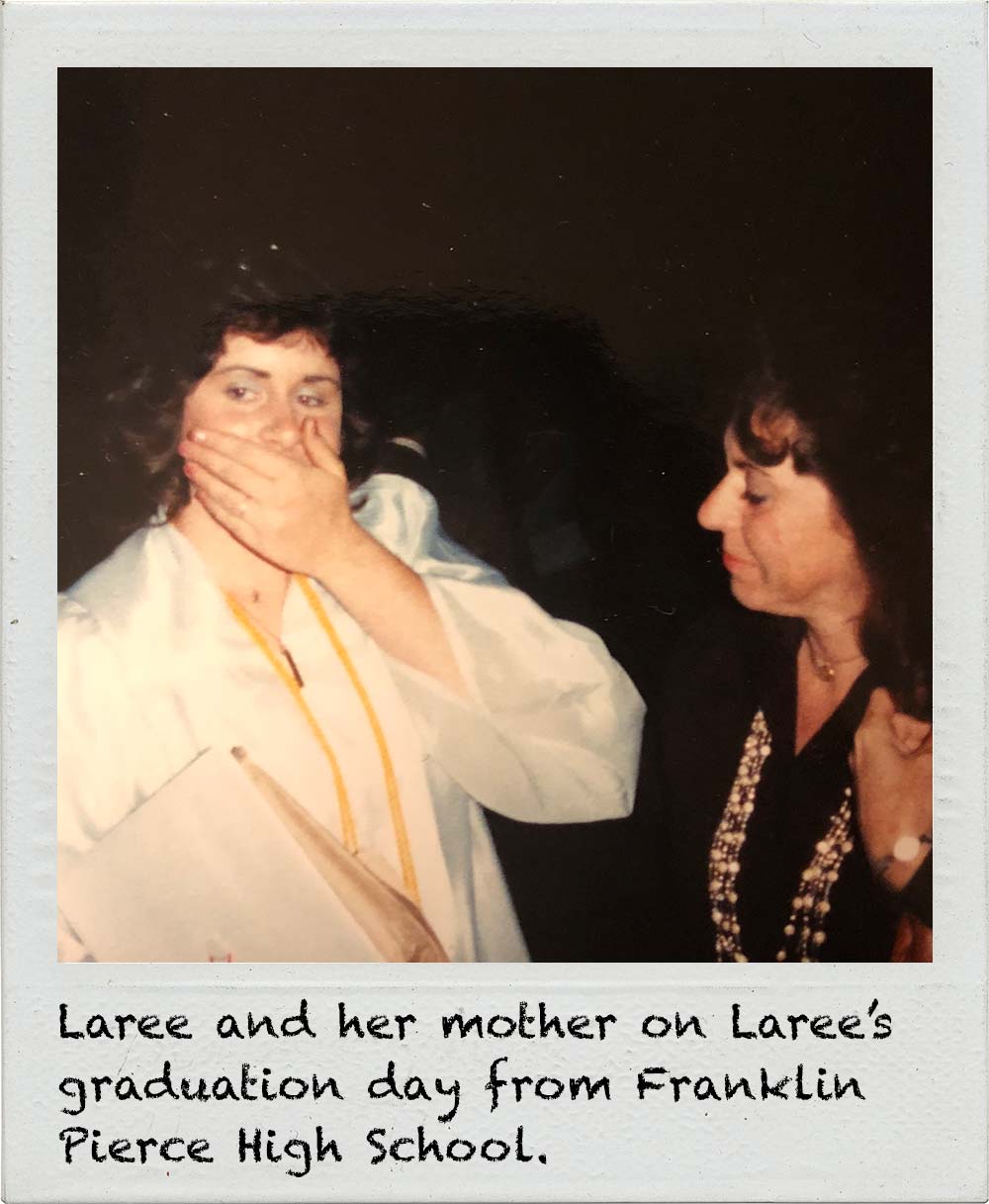

She’s a first-generation graduate who navigated a long, winding path to a religion bachelor’s degree from PLU. It took two attempts to earn an associate degree from Pierce College, with a wedding and a baby in between. After five years working in the medical field and welcoming her second child, she thought she would go back to school for nursing.

“I had an epiphany,” she said. “I can do this, but I don’t know that I should do this.”

So, she didn’t. After eight years as a stay-at-home mom, Winer went back to work in K-12 education. She worked a laundry list of jobs at Cascade Christian Schools in Puyallup, from administrative assistant positions to fundraising work.

After outgrowing those jobs, Winer said, she worked as a professional organizer, pondering her next move.

Though she didn’t know what came next, she knew college was at the top of her list.

“I wanted to finish my degree so much,” she said. “It frustrated me to be in jobs that were just jobs. I didn’t know if the work was meaningful.”

Then, sitting at Marzano Italian Restaurant with her husband in 2005, Winer spotted banners across the way that spoke to her: “What will you do with your one wild and precious life? What’s your vocation?”

Laree Winer '15, Associate Director for Student Engagement and the Center for Vocation

PLU’s mission found Winer in the right place at the right time. She snagged an informational interview with human resources, thanks to a client’s connection to the Office of Advancement.

“I just started applying for anything I could to get my foot in the door here at PLU,” she said.

An administrative job with the Division of Social Sciences in 2006 led to valuable mentorship by faculty members, who quickly realized Winer was overqualified for the work she was doing. She eventually landed in Student Life, where she remains today, and started pursuing her degree in 2009.

Winer took a class every term while working full time for the university, finishing with a 3.98 grade-point average upon graduating in 2015. The only B on her transcript was in philosophy.

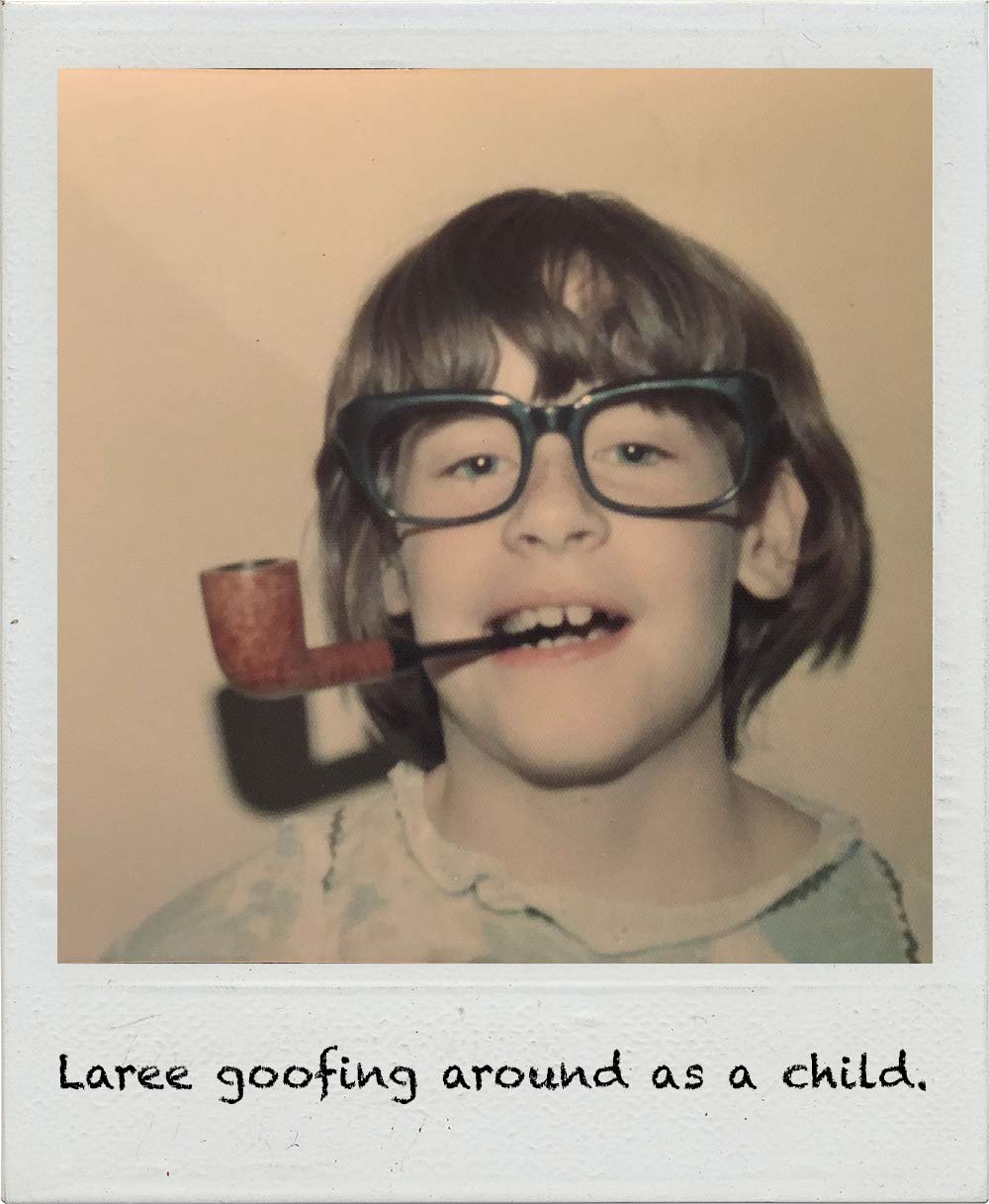

“I always did really well in school. A learner was a big part of my identity,” she said. “I loved to read, I loved to write, I loved to learn.”

The intelligence runs in the family, she noted.

“My mom was incredibly intelligent,” Winer said, adding that the family spent so much time at the old Parkland library on Garfield Street that the staff offered her mom a job. She worked in the local library system until she died in 2001. “Had she had a degree, she could have done so much more and that made an impression on me.”

“My mom was incredibly intelligent. Had she had a degree, she could have done so much more and that made an impression on me.”

– Laree Winer

Winer’s dad, who proudly watched his daughter cross the commencement stage on her 50th birthday, is pragmatic and sharp. “My dad has a tremendous work ethic,” she said. “He’s really smart. He reads voraciously.”

Tears welled as I talked to Winer about her parents — because they remind me of mine.

My mom dropped out of high school not once, but twice. I was in eighth grade before I found out. That’s when my mom was studying for the test to earn a GED certificate, right before she took an entry-level job at a title company. After years of working her way through the ranks, she became a licensed limited practice officer and subsequently one of the top escrow closers in her company. Now, she’s a manager who has transformed the performance of the branch she leads.

And she’s one of the smartest people I know.

“I am not ashamed of it at all,” my mom recently told me. “I feel like my story could inspire someone.”

Just like Winer’s dad, mine has an unwavering work ethic. I don’t have the space to list all the jobs my dad has worked. He excelled equally in all of them. But my dad’s biggest impact on me has been his relentless consumption of newspapers and his staunch life lessons.

He has an associate degree, and started studying business finance at the University of Alaska Juneau before a great job opportunity in retail management and building a family took him down a different path.

What does it mean to be first in the family?

“He just couldn’t pass it up,” my mom said. I’ve been reminded a lot that the job completely covered medical expenses when my two younger sisters and I were born within five years of each other.

My dad was my voice of reason during college: “whatever you study, make sure it pays the bills.”

Winer can relate.

“Well, what are you going to do with that?” she recalled her dad asking, in reaction to the religion courses she was taking. “There’s this practicality to it,” she said.

Winer knows that’s a struggle for many first-generation college students, making it that much sweeter when the breakthroughs happen.

Still, the practical side of being first in the family adds value to the overall college experience that other students may not reap.

“They come with a realistic knowledge of the outside world,” Winer said. “They come fully aware of the challenges, fully aware of the obstacles. And yet they still, despite full knowledge of those things, have incredible hope. They have a grit and resiliency and work ethic.”

And they approach their education with eyes wide open.

“First-gen students have an eagerness, they have an appreciation, they have an openness to not just the content, but the mentoring that is readily available here,” Winer said. “There’s such a hunger for mentoring.”

‘Part of the fabric’

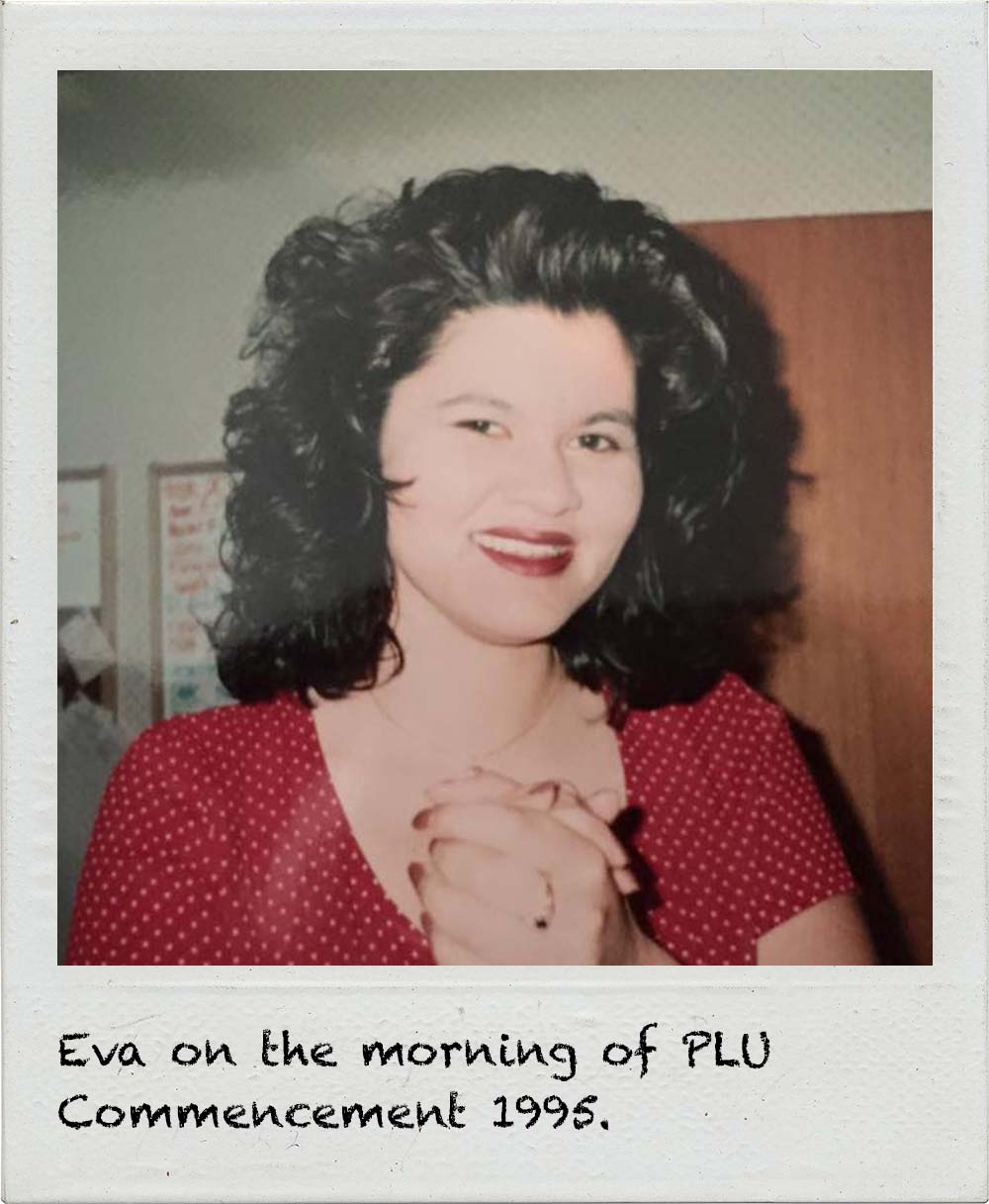

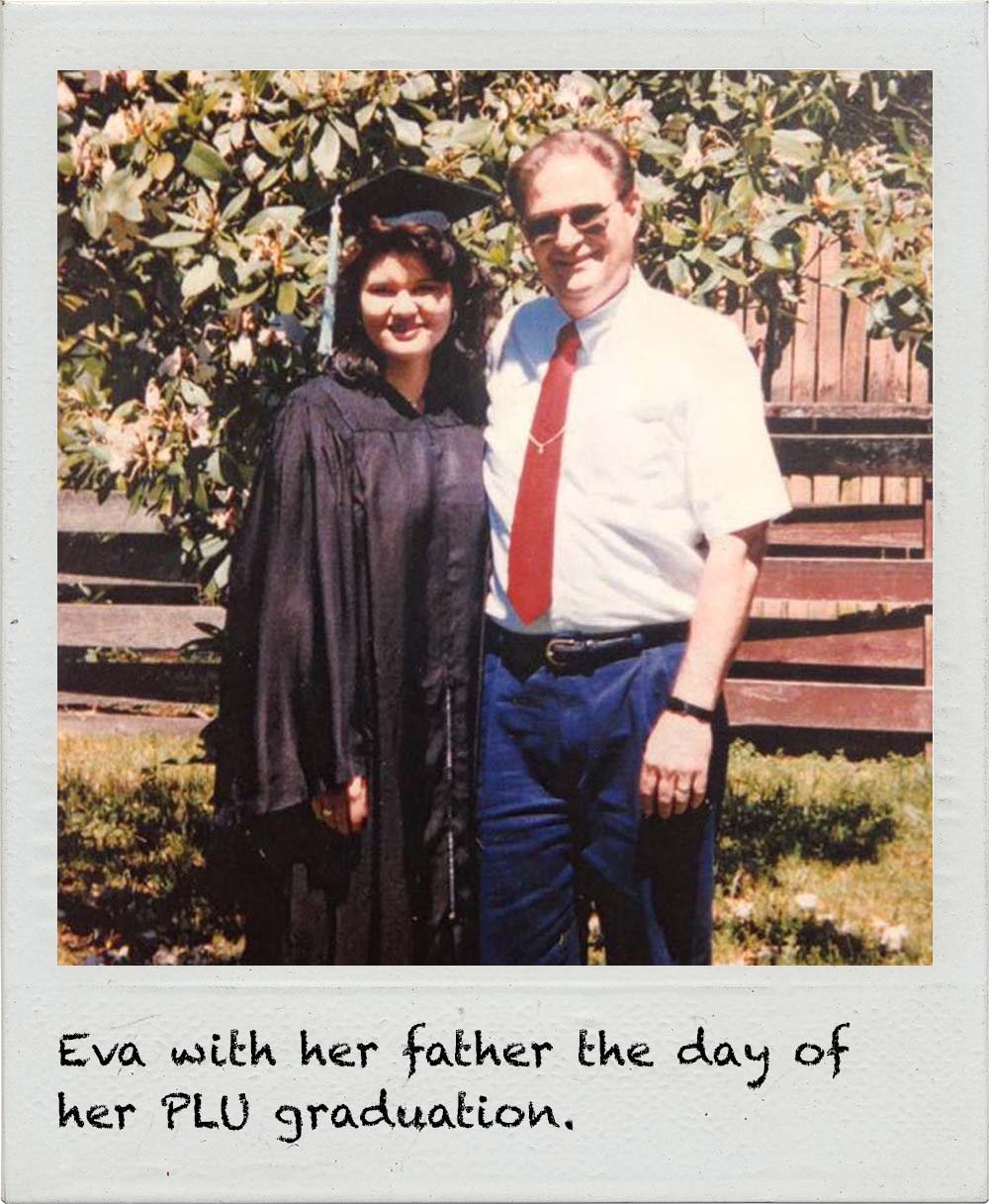

Eva Frey ’95 was always the smart girl.

“The most salient identity up to that point in my life was that of a student,” she said of her teenage self. “So what else was I going to do but go to college?”

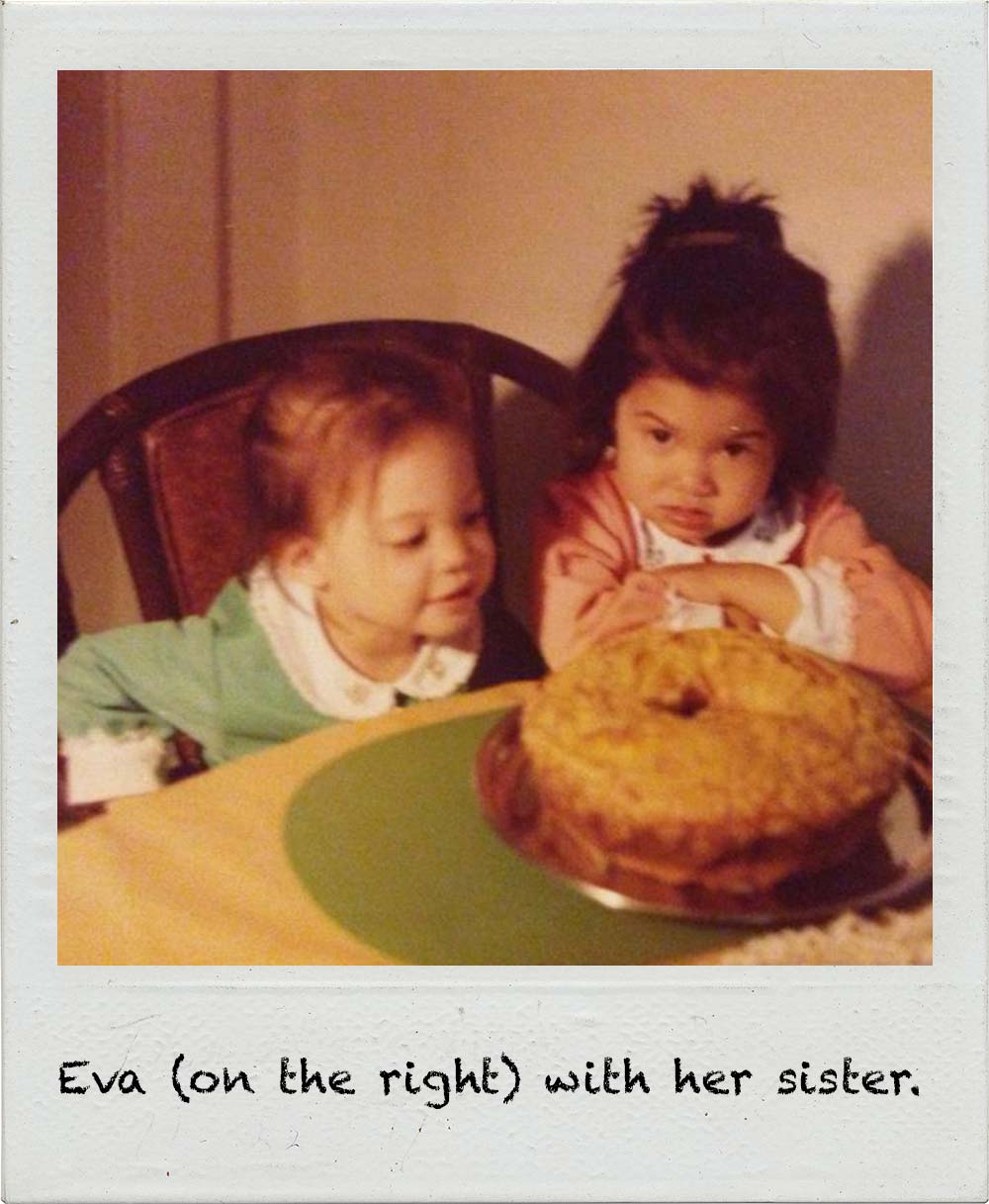

Despite coming from parents who couldn’t afford to pursue higher education, Frey says it was never a question for her and her sister. “The active conversation in our family was ‘you girls will have more than what your father and I had.’”

That included swimming and piano lessons, trips to museums, and anything they needed to thrive at school.

“I was first in the family, but I was also free and reduced lunch — government cheese and peanut butter and the whole nine yards,” said Frey, now the dean of students at PLU. “But my parents never made us feel like we didn’t have enough to do whatever we wanted to do.”

Eva Frey '95, Dean of Students

When she came to the university, she didn’t know who around her shared a similar background.

“When I was here as a college student, you did not tell people you were first in the family,” she said. “I knew for sure people could tell I was first in the family because I didn’t have a bathrobe. All the other kids on the wing had a bathrobe.”

It was an item, among many, that didn’t jump out as a necessity to a family who lacked the cultural capital to anticipate how to prepare for college.

It wasn’t until Frey told me about her experience with a residence-hall fire alarm sans bathrobe that I realized I didn’t have a bathrobe during my time living at PLU, either.

It wasn’t for a lack of preparation, though. Despite living nearby, my mom compiled a massive list of must-haves before I hauled my things to Harstad Hall in fall 2007.

I didn’t have a bathrobe, but I definitely had a shower caddy.

As for Frey, her dad bought an elaborate “shower caboodle” that stood tall and doubled as a seat with storage. “My dad had a very literal interpretation of what was needed to come to college,” she said, adding that her parents were “all in.”

Frey says these experiences inform how she approaches student development in her role at PLU, especially when dealing with first-generation students. The representation she and other administrators across campus offer helps create a sense of belonging that wasn’t as accessible in the past.

“Representation is important because education is about growing your knowledge base and your experience base,” Frey said. “And that doesn’t just happen by what you learn in the classroom, it happens by who you sit next to.”

And, Frey added, sometimes the person you sit next to may represent perspectives that are invisible.

“Representation is important because education is about growing your knowledge base and your experience base. And that doesn’t just happen by what you learn in the classroom, it happens by who you sit next to.”

– Eva Frey

It’s why Elizabeth Barton, psychologist and associate director for training and outreach in PLU’s Counseling Center, stresses that representation alone isn’t enough. “We have to articulate that experience,” Barton said. “Just being is not the same as advocating and sharing that story. There’s such power in finding like-minded people.”

When I was at PLU as a student, I didn’t talk about my experience as a first-generation student, mainly because I was unaware that it was remarkable. Still, I always felt like I was on an island. At the time, I failed to articulate why I struggled to relate to my peers.

Now, I understand what made me different, and I envy the first-in-the-family students who can see themselves modeled — and celebrated — in the administration.

“Not only are there a lot of us, we don’t try to hide our identity,” Frey said. “We invite and we normalize that first-in-the-family exists. We don’t shame it.”

Frey says PLU is leaving behind the so-called deficit model of approaching first-in-the-family support, which can push those student narratives to the shadows.

How do you talk about being first in the family?

What challenges do first-in-the-family students face?

“By bringing it out in the open we are pushing ourselves, as an institution, to increase the capacity to understand the opportunities and strengths of those who are first in the family and help them be even more successful,” she said. “It’s part of the fabric of this place.”

Frey admits her title sometimes makes it harder for first-generation students to see their experiences in her. But often it shows them what’s possible.

“Being Dr. Frey, being the dean of students, stands about 50 feet in front of me. And there are students who can never get over that,” Frey said. “Then there are students who get over it, and find me a role model of what can be achieved. And then there are students who actually engage with me in conversation about how do you do this.”

She also admits there are times when she hides her title — in part to avoid “flaunting it,” but also to settle into the space between the academic world and the world that came before it.

“I work in education, so I live in a cerebral world,” she said. “My entire family lives in a military world.”

She recalls a recent conversation with her sister — who holds a graduate degree from Georgetown University: “Why do you always have to use the biggest words possible?” Frey recalled her asking. “Normal people don’t sound like you, Eva.”

Barton says code-switching — or constantly shifting between cultural identities — is common for first-generation college students. It can involve balancing the desire for new opportunities with the nagging pressure not to get “too big for your britches,” she said.

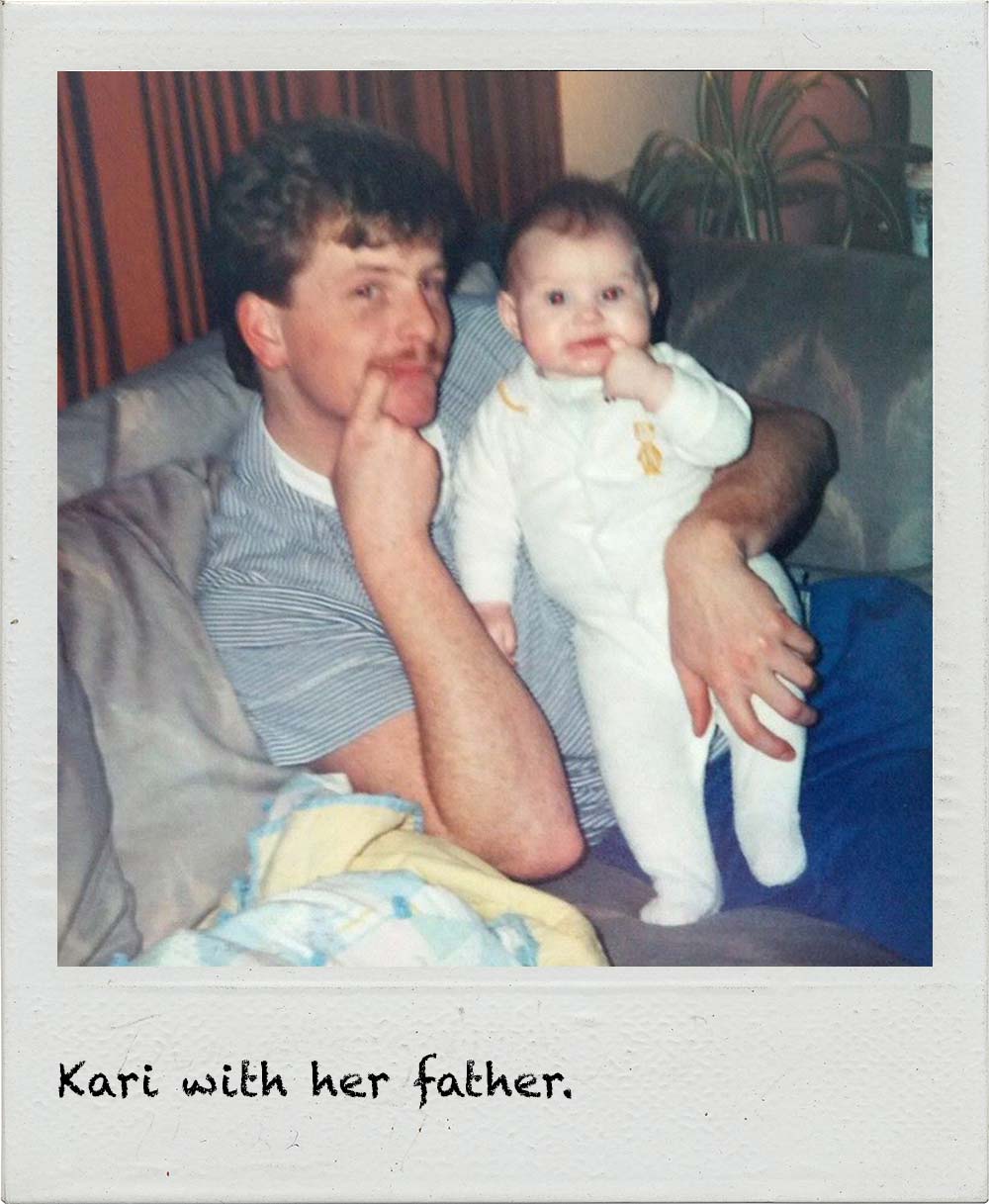

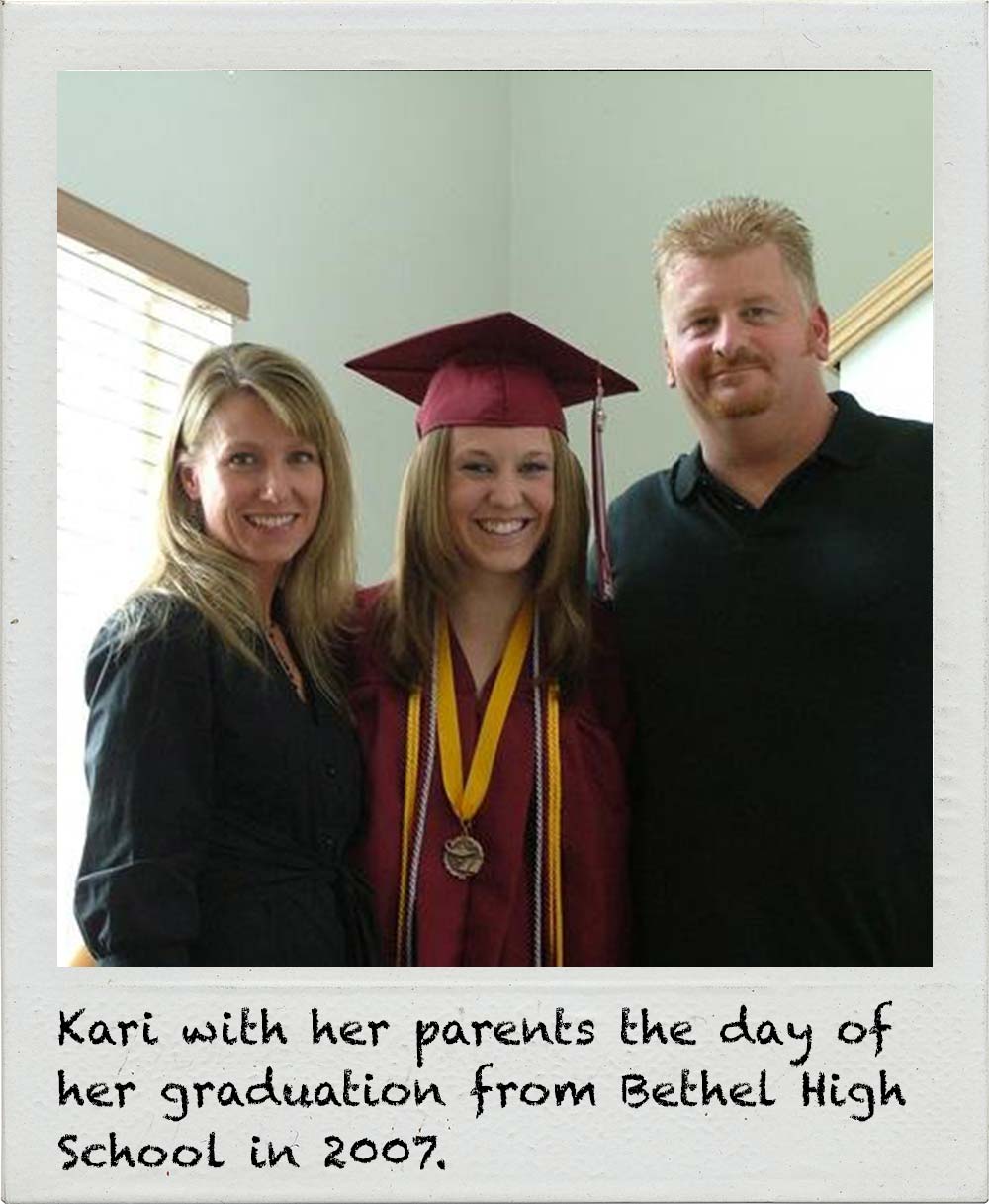

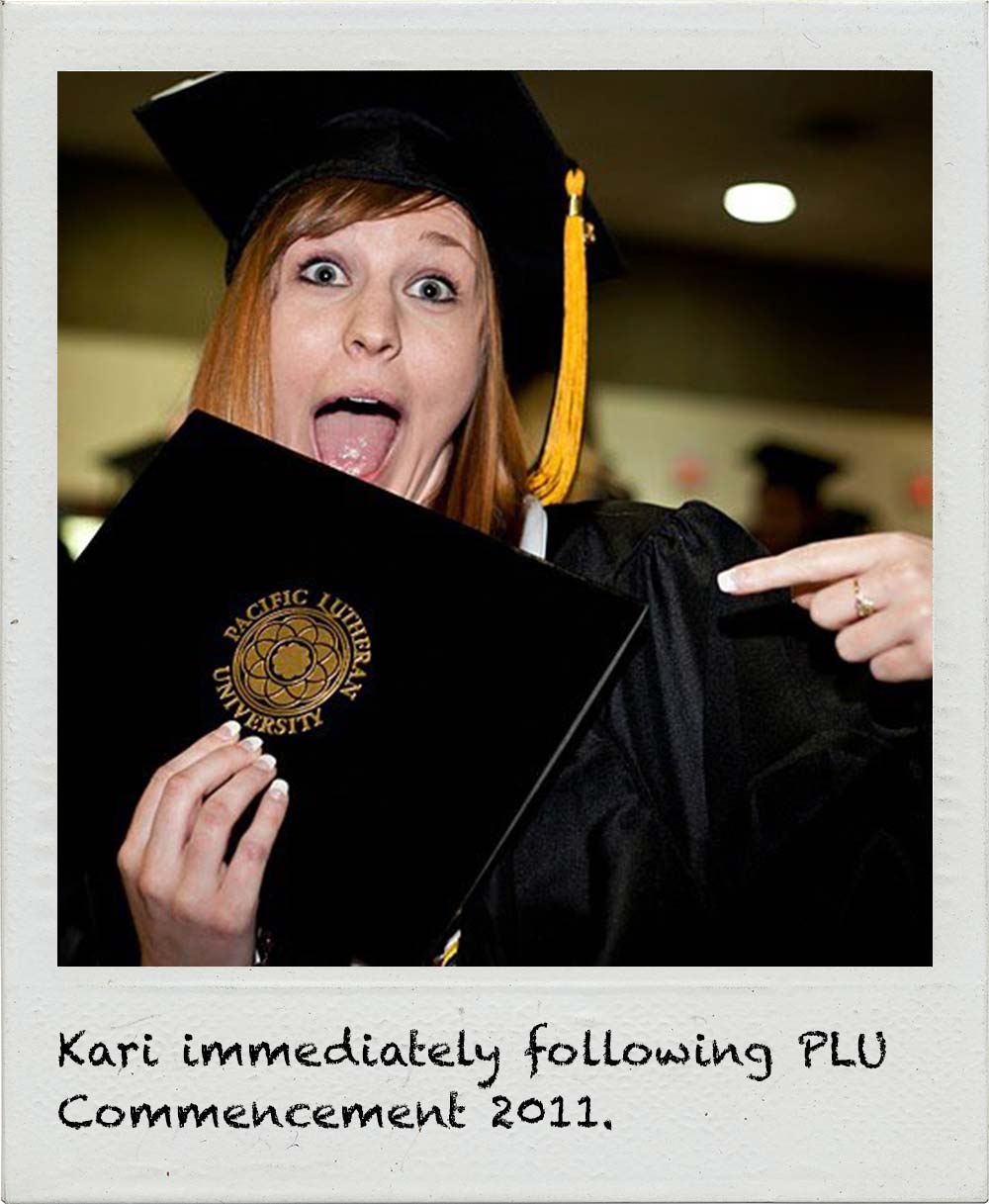

Kari Plog '11, Senior Editor for Content Development

“It’s feeling like they don’t belong in either world,” Barton said.

However, Barton added, students caught in the middle of the two worlds also benefit from the push and pull. “They get to decide what to accept and reject,” she said, embracing identity development more intentionally.

When I code-switch, I find myself yearning to transfer the most valuable parts of my college experience to my family. Specifically, the PLU brand of vocation.

My parents have always worked good jobs. More recently, those good jobs have come with even better salaries.

For many first-generation students, money is a motivator because it’s what they’ve come to understand as the marker of success. After all, how can you feel successful if you can’t pay your bills?

What PLU taught me — and continues to teach other first-generation students — is the value of fulfillment.

“It’s about wholeness and completeness, freedom and liberation,” Winer said.

That liberation is something I’ve always wanted for my parents, who are smart and work harder than anyone else I know. Reflecting on the liberation I’ve slowly seen my mom achieve, culminating in a recent late-night phone call, is what brought tears to my eyes in Winer’s chair.

What value do first-in-the-family students bring?

Following an after-hours work gathering she organized for her staff, my mom called to share a feeling of fulfillment I’ve rarely seen in her when discussing her work.

“I’m just so happy with what I do,” she told me. “And I’m so good at it.”

Little did I realize at the time, that moment stayed with me. It bubbled to the surface as I sat across from Winer in the chair.

“Your mom is such a perfect example of the freedom,” Winer said. “The reason why you get so emotional about it is because you’re hearing her freedom. You’re seeing her emerge and be whole, and be awesome in ways that you haven’t seen before. And that’s powerful.”

‘Loud and proud’

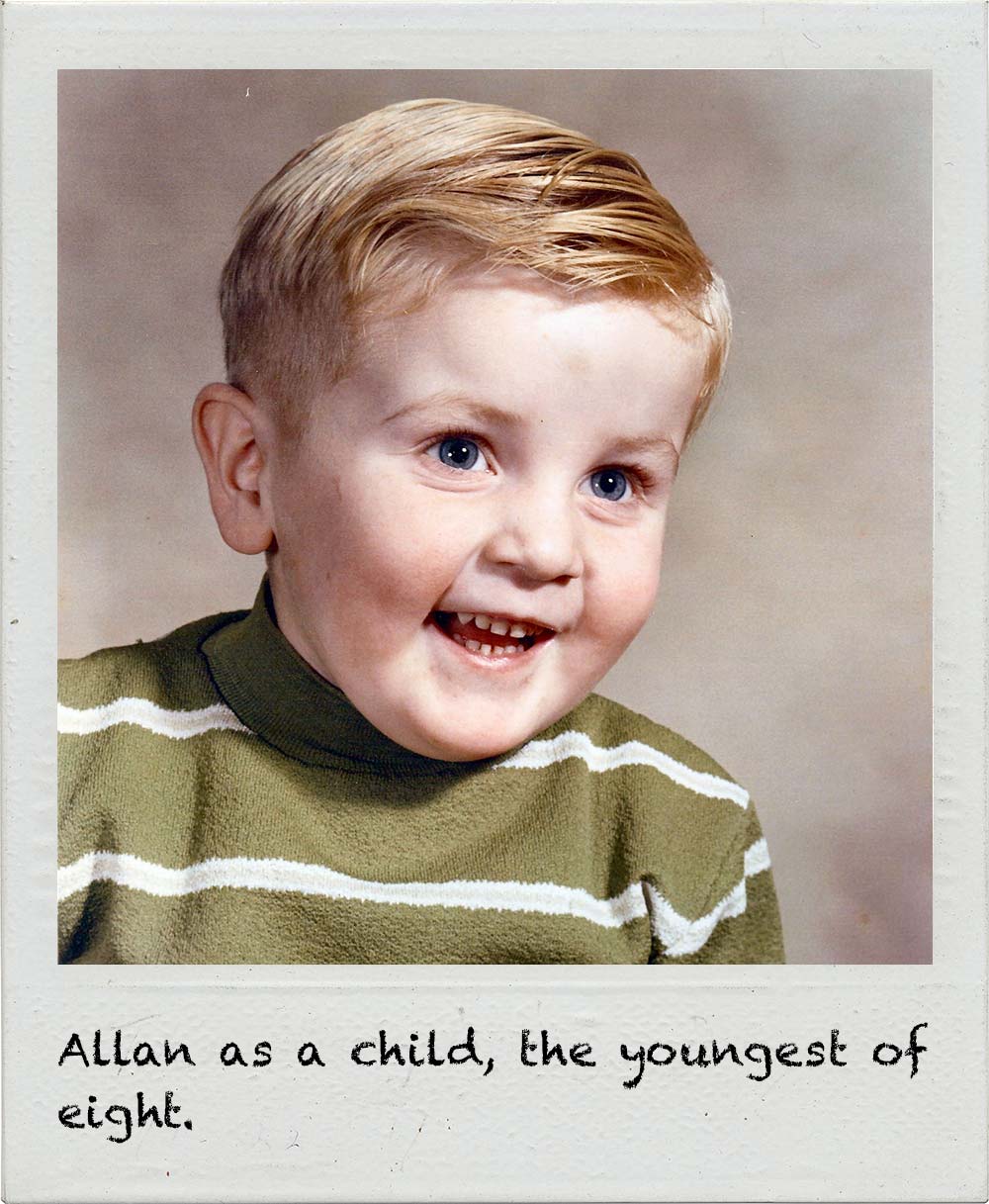

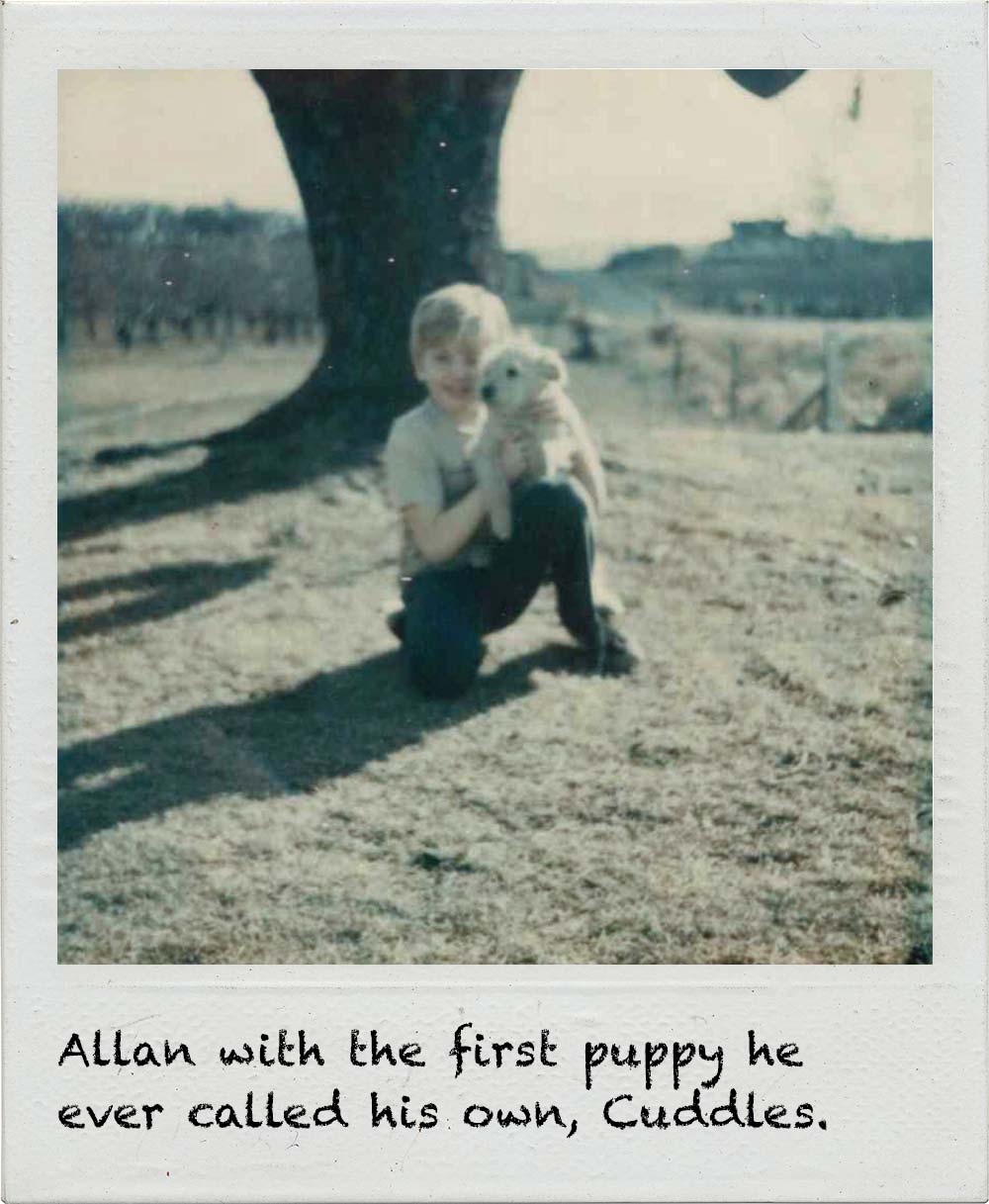

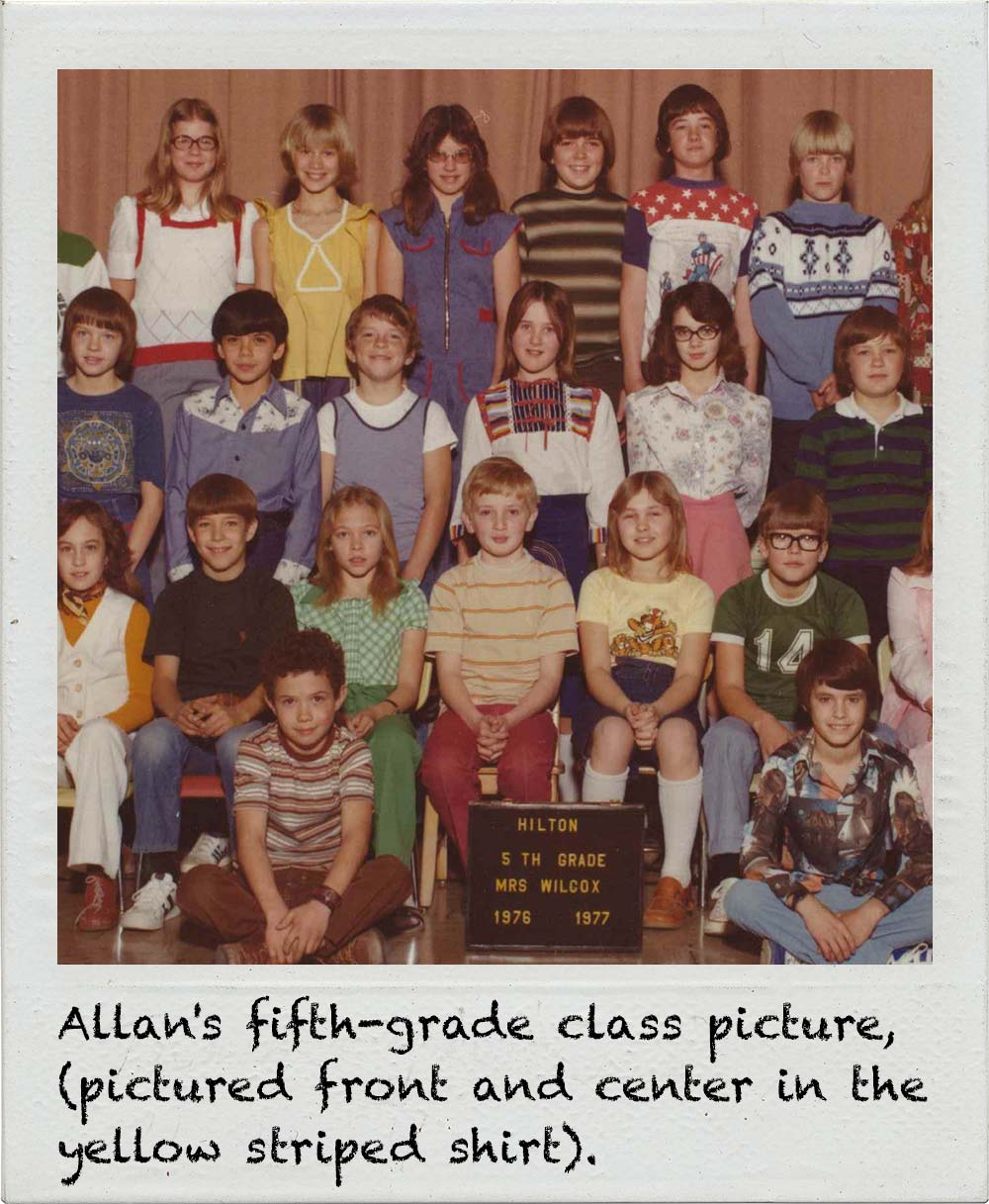

Acting President Allan Belton says he was the “quirky brainiac” growing up — the youngest of eight with parents who were products of the Great Depression.

But unlike his colleague Frey, Belton never talked about college at home.

“It was a big deal to be the first,” he said. “Nobody had that personal experience, so we didn’t talk about it.”

That changed when a new counselor arrived at Zillah High School, which only had about 150 kids at the time. Belton still remembers her name: Karin Thompson.

“She saw something in me that I didn’t see in my future,” he recalled.

The counselor convinced Belton’s friends to drive him to and from the SAT, to guarantee he took the test. After that she asked him, along with a couple of his peers, to complete a form and an essay.

“I didn’t know what it was for,” Belton said.

Allan Belton, Acting President

When Thompson handed him the envelope that notified him of his full-ride scholarship to any state school in Washington, she asked him what it meant to him.

Even then, he wasn’t sure: “I think it means I’m going to college,” he recalled saying. “It was quite a shock. I had never visited a university.”

Soon, that changed. After a tour around the state, he chose Washington State University. He still remembers standing outside his residence hall with a single box and a fast-food burger, alone and bewildered.

“I didn’t know how to check into my room,” he said. It wasn’t until well into his first year that he learned about the concept of dropping classes. “I had to go through those processes on my own.”

Belton knows other first-generation college students — at PLU and beyond — have similar stories. He also knows, and appreciates, the valuable lessons learned from them.

“A lot of first-gens are just self sufficient in many ways when it matters,” Belton said. “You have to have some level of independence. Teaching yourself how to do things despite nobody showing you how.”

Belton gained a lot of independence even before coming to college: he worked countless jobs in orchards, raised pigs, stocked shelves at a local grocery store, babysat neighbors. He even did his parents’ taxes from the time he was 13, since neither of them graduated high school.

What advice do you have for first-in-the-family students?

“I made more (money) out of my first year of college than my parents ever did combined,” Belton said. “That’s just eye opening. You can’t teach the ability to find a way to get things done.”

Much like myself and others, Belton didn’t broadcast his first-in-the-family status. He counts himself lucky for stumbling into a support network that helped him thrive. His roommate’s brother already had two years under his belt at WSU, for example.

He has learned how vital it is for him to talk about his past, especially in his role leading the university. It’s why he wears his “proud to be first in the family” button, and why he shares his story with the PLU community at every opportunity.

“I don’t know if we do enough, and I don’t know if you can ever do enough,” Belton stressed. “One of the biggest challenges any university has in serving first-in-the-family students, and the biggest challenge any first-in-the-family student has, is finding each other.”

First-generation students don’t often “raise their hands” to be identified, Belton added. “They will pretend they fit,” he said. “They don’t want to stand out.”

The culture at PLU is working to foster a sense of pride among those who come first. “The only reason I would say we’re doing better is because we’re talking about it,” Belton said. “It’s tough as a first-gen, but the most important thing you can do is be loud and proud about it. No one is going to know you’re first-gen unless you say it. And it’s nothing to be embarrassed about. It’s something to be proud of.”

And there’s a lot to be proud of: self-reliance, understanding the value of a dollar, owning your success, and changing the story for those who come after you.

Belton, who was dubbed “Harvard” by his family after heading to college, became a role model for younger members of his very large family.

“Everybody just started going to college,” he said. Nearly all of Belton’s nieces and nephews earned degrees, he added. “That’s probably my favorite part of the story of being first-gen. I won’t be last-gen.”

“It’s tough as a first-gen, but the most important thing you can do is be loud and proud about it. No one is going to know you’re first-gen unless you say it. And it’s nothing to be embarrassed about. It’s something to be proud of.”

– Allan Belton

More importantly, PLU students can look to Belton — and Frey, and Winer, and roughly 60 faculty and staff members across campus — and see the possibilities for themselves.

“I went from shaving pigs’ ears with Nair to being a college president,” Belton said. “So yeah, anyone can do it.”

As I pored over palpable stories of my peers’ experiences as first-generation students, I found a common thread that tied all of our stories together: limitless optimism.

“Many first-gen students come in with a different sense of what’s possible,” said Barton, the university psychologist.

“I think first-gens have a different orientation toward the opportunity (to attend college),” Winer said. “We recognize the privilege in a different way.”

“It’s amazing what you can have when you make that your expectation,” Frey said.

“Sometimes it’s just finding a way when there’s no path,” Belton said. “That’s not really adversity, that’s just part of the DNA of being first of anything.”

I am so proud to be first, for all that’s mentioned above and more. And while I’m grateful for the cultural capital I’ve gained from my college experience — to inevitably pass on later — I sincerely hope I find a way to transfer what I gained from a lack thereof.