Keven Drews ’16

“You have to raise $500,000 or you’re going to die.” In so many words, that’s what Keven Drews ’16 says his doctor told him over the phone in October, when Drews learned he was out of options in his longtime fight for his life.

Drews has faced a 14-year battle with multiple myeloma, a cancer formed in the body’s plasma cells. His last hope is a clinical trial at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, with the half-a-million price tag.

“I got 14 years,” he said. “I’m hoping to get more.”

Drews recently graduated from Pacific Lutheran University’s Rainier Writing Workshop, the low-residency Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing, after spending years working as a journalist in both Canada and Washington state. He finished the program in 2016, 13 years after receiving his diagnosis.

Drews was living in the U.S. in 2003, working in Port Townsend for the Peninsula Daily News, when one of his spinal vertebrae came apart.

“When I felt my vertebrae and accompanying back spasm it was sort of like a blunt knife going into my back,” Drews said.

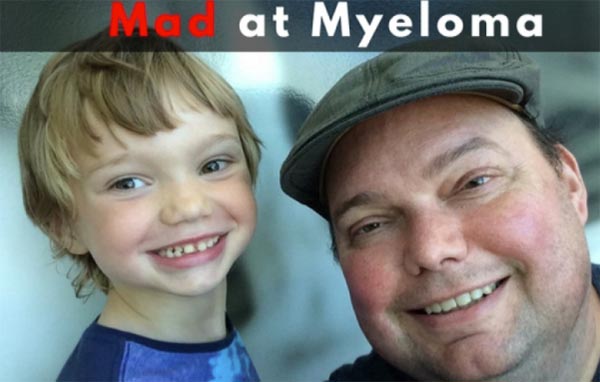

Multiple myeloma is a cancer that starts in the plasma cells, which are mostly found in bone marrow. The cells then collect to form tumors called plasmacytoma. According to the American Cancer Society, most cases of multiple myeloma are found in patients who are 65 and older. Drews is 45.

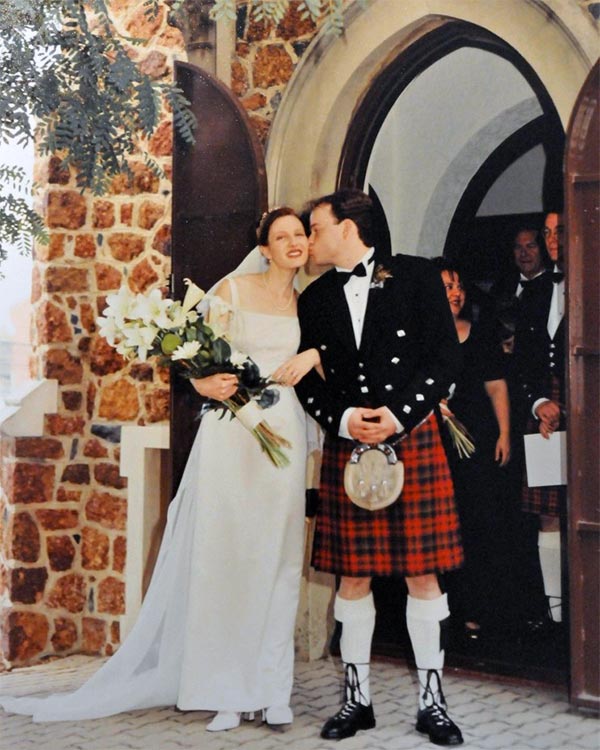

He was 31 when he moved to Washington, to get acquainted with the country where his life started. Drews was born in Spokane and has dual citizenship in the U.S. and Canada. He currently lives in Surrey, British Columbia, with his wife, Yvette, and their 7-year-old twins.

“I have this birth certificate that says I am American and a passport that says I am an American,” Drews said. “So what does that mean? And to find out what that means I had to live there.”

However, once it became obvious that Drews needed serious medical attention, his plans changed. With his wife living in B.C. and the high cost of health care in the United States, Drews decided to return to Canada. He received a stem cell treatment in 2003 and has had several major relapses since his original diagnosis. The most recent relapse occurred while he was studying at PLU.

“I was a little concerned if I could make it through the program because of my health. You’re gambling here. What if you get hit by a major relapse?” Drews said. “And I did, right in the middle of thesis season.”

“The first thing I will say about Keven is that he was beloved by a lot of people in the program. He’s got a really winning personality and he’s also incredibly smart and talented as a writer, and especially hardworking despite the fact that he was dealing with so many grave medical issues.”

– Rick Barot, associate professor of English and director of the MFA program

Drews had been working for The Canadian Press when he decided to apply to PLU.

“I didn’t feel satisfied with where my life was at that point,” he said. “The Canadian Press is an awesome place to work, but I wanted to do something more academic.”

Drews was a perfect fit for the program, said Rick Barot, associate professor of English and MFA director.

“The first thing I will say about Keven is that he was beloved by a lot of people in the program,” Barot said. “He’s got a really winning personality and he’s also incredibly smart and talented as a writer, and especially hardworking despite the fact that he was dealing with so many grave medical issues.”

The three-year MFA program includes four summer residencies in which students spend 10 days on campus. The rest of the year is spent working with individual mentors. Drews’ concentration was nonfiction writing, and his work focuses a lot on his life and struggles with cancer.

His current project — an essay about his life — is on pause due to his fundraising campaign for the clinical trial. Still, he uses Facebook posts as an outlet — to provide a window into his daily life.

“I can’t just sit here and feel like I am doing nothing. I spent 20 years of my life writing in one form or another,” Drews said. “(Readers) might not make a donation but at least they can know what it is like to live with this kind of stuff.”

When Drews was on PLU’s campus, he would share his work with other students. Much of it related to his cancer.

“I think for lot of people it was challenging to read that material but I think they understood what was at stake, because he was right there showing that you could fight something and fight it with a kind of clarity that he did,” Barot said.

In addition to logging his daily life on social media, most of Drews’ days are spent at home with his children. For Yvette Drews, the possibility of losing Keven with kids in the picture has made this recent development frightening.

“It has made everything get really real – really quickly,” Yvette Drews said. “It is scary to think about what the future could be, raising two children, one on the autism spectrum, by myself.”

But hope is not lost, just pricey.

“Until now, the system up here works generally by you walking into a doctor’s office or an emergency room and popping down your care card on the back of your driver’s license,” Keven Drews said. “There is no paying up here. You just go to the doctor or hospital and then you get better. And raising money just adds so much more stress.”

The financial situation is tricky for Drews. Because the procedure is in the United States, the provincial government is hesitant to pay, but the experimental nature of the treatment and lack of FDA approval means it is highly unlikely he can get state sponsorship.

Drews explained that the clinical trial takes the body’s T-cells and re-engineers the cell DNA to attack the dangerous cancer. He says similar trials have been used for patients with leukemia and lymphoma.

“We are really lucky here in North America,” Drews said. “We can access these treatments.”

Drews’ GoFundMe page has raised more than $30,000 and he is headed to Seattle in the next few weeks for a pre-trial consultation. In the meantime, he’s appreciating each day and encourages others to do the same.

“Enjoy life,” he said. “Don’t waste time. Don’t waste seconds.”