When Hilde Bjørhovde ’80 returned to Norway, fresh out of Pacific Lutheran University’s journalism program, her home nation had one television station.

It wasn’t long after, however, that the minister of culture greenlit efforts to launch commercial TV and radio, Bjørhovde recalled.

“So, I was there at the right time,” she said, over lunch at an ornate cafe at Hotel Bristol in the heart of Oslo.

Bjørhovde became the first news anchor on a newly minted, once weekly program. “It was just experimenting,” she said. “It was on a very small scale.”

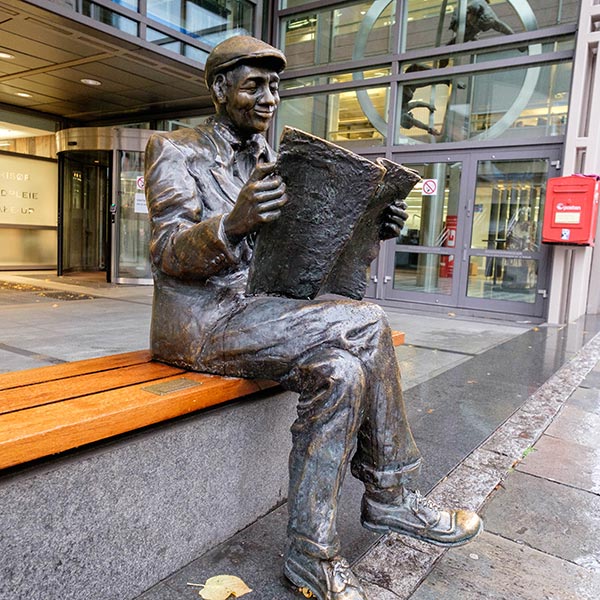

Now, decades later, Bjørhovde is a senior reporter at the center of a very different media landscape. She covers arts, cultural affairs and more at Aftenposten, a national newspaper she says is innovating in the world of multimedia journalism.

“Aftenposten is leading Europe in making people pay for digital news,” she said. “We have many platforms. We have made a big transition.”

And it’s an approach that’s working, counter to the narrative in many newsrooms across America. “We’re managing to get people to subscribe to our digital content,” Bjørhovde said, noting that online subscriptions recently surpassed 100,000 and are on the rise. “And, of course, they get the newspaper on their e-pads.”

So, Bjørhovde’s career nearly bookends the contemporary evolution of newspapers, starting with her training at PLU. “We didn’t even have typewriters in the classroom,” she said, laughing. “We were writing by hand. It was very last-century stuff.”

But the values she gained were timeless.

“We were encouraged to always be curious,” she said.

Bjørhovde praised PLU’s intimate classes and easy access to professors, including retired Professor Cliff Rowe, who had just started splitting his schedule between The Seattle Times and PLU around the time Bjørhovde arrived.

Rowe said she was one of his first Norwegian students. He remembers her as bubbly, outgoing and a natural at the craft.

“Her writing was just so good,” Rowe said.

Bjørhovde credits her degree, in part, to her longtime mentor. Originally, she intended to come to the United States for one year and one purpose: to study journalism. When she arrived on PLU’s campus in 1977, all the classes she planned to take were full. She needed Rowe’s approval if she had any chance of enrolling in that first news-writing class and sticking to the plan.

He granted it. Bjørhovde became one of the first Norwegian exchange students to study journalism at an American university as part of her country’s program Lånekassen, or Norwegian State Educational Loan Fund, which allocates loans and grants for college students in Norway.

“That opened totally new horizons,” she said. “Norwegian students are very fortunate to have this possibility.”

So, her yearlong agenda expanded to an extended stay, during which she earned a degree in broadcast journalism with a minor in political science.

In between academic years, Bjørhovde traveled home to work as a summer intern in Norwegian newsrooms. During her semesters at PLU, she was an active student journalist.

“I value what I learned from writing for The Mast,” she said. “I value what I learned working in the TV studio.”

She also had the opportunity to pick the brains of professional reporters, thanks to Rowe, during a tour of The Seattle Times newsroom, among other professional development opportunities.

Rowe said PLU’s journalism program was the perfect beginning to Bjørhovde’s storied career. He said the clear intersection of Norway’s values and PLU’s mission helped shape her and others into responsible, thoughtful and empathetic journalists.

“It’s a great place for her to reinforce what she already knew,” he said of Aftenposten, which translates in English to “The Evening Post” despite being a morning newspaper. “She took away an appreciation for good journalism and she had an environment back home where she could use it.”

That environment, Rowe added, is a country that touts one of the largest media readerships in the world. Norway’s government helps subsidize media outlets, an unusual approach compared to the independent press in the U.S.

Rowe admits that his initial uneasiness about that government aid has turned into appreciation. He believes Norway’s society is better for having a government that values thriving media. “It preserves newspapers all over,” he said.

Bjørhovde says the responsibility of preservation also lies with publications, including Aftenposten.

“We are in the middle of a big revolution,” she said.

As a self-proclaimed “old-school” reporter, Bjørhovde admits her preference for print. “I feel like if it hasn’t been in print, it hasn’t existed,” she quipped. “I love it when I have big stories in the paper. You can go back, you can fold it. But, of course, we are doing stories on all platforms.”

Aftenposten is doing that and then some. In addition to the web and print versions of the daily product, the company produces several magazines, podcasts, exclusive events, television and video programs, livestreamed press conferences and concerts, and more.

The company even produces Aftenposten Junior, a world-news publication geared toward children. Sometimes, Bjørhovde added, the news is produced by kids who are granted interviews with important figures such as the prime minister.

“It’s a huge success,” she said of the award-winning newspaper.

Bjørhovde writes news articles of varying depth for Aftenposten. The fall lunch at Hotel Bristol granted her a brief break from work on an in-depth piece about sexual misconduct in the acting world, spurred by the #MeToo social media movement.

“Today I’ve been on the phone with some of our most renowned actresses,” she said, including Academy Award-winner Liv Ullmann. “I have some more calls to make.”

The article, similar to the paper’s other important journalism, will hide behind a paywall to entice readers to pay for the hard work of Bjørhovde and her colleagues. She says it’s a better model than the click-based one many media outlets rely on — wishful thinking that has media owners counting on clicks translating to dollars.

“Our core readers are well educated. They’re smart, they’re interested in being enlightened about what’s going on in the world, and we are working very hard to give our readers a quality newspaper in Aftenposten,” Bjørhovde said. “But they have to pay for it.”

They are, she says, and not just for the content available to read. Readers also are attending exclusive live events, during which reporters are on stage interviewing prominent leaders and experts on various topics. Readers even purchase subscriptions to livestream classical music performances, she added. “Something as narrow as classical music,” she said, “people are willing to pay for it.”

Bjørhovde stressed the model is community-centered, not top-down, so she is involved in rolling out the new brand of journalism along with her colleagues. She said it’s more important than ever that Aftenposten and other media outlets adapt to the changing world.

“Fake news? It’s just a bunch of rubbish,” she said. “Quality journalism is very important. But we have to finance it. And that is where we have to find new ways.”

She’s confident the industry as a whole will find those new ways, and she’s sticking around to see it through.

“Journalism will not die,” she said.